This item was originally written for the newsletter of Newcastle Family History Society

In the midst of life we are in death

This haunting sentence has a long history. In its Latin form it’s an ancient Gregorian chant and it is familiar to many as part of the burial service in the book of common prayer. As a reminder that the dead are always with us, and that – as Shakespeare memorably observed, “our little life is rounded with a sleep” – the sentence is natural epitaph material.

It was, for example, engraved on the tombstone of Samuel Osborne when he was laid to rest in the grounds of Christ Church Cathedral in Newcastle, NSW, in 1864.

Those who habitually paddle their feet in the currents of time may occasionally state their belief that they have felt “guided” to some piece of information that brings them closer to understanding things that were important to a dead person. Sometimes it feels as though the guide might have been the dead person themselves, however improbable that sounds in our purportedly rational day and age.

That’s certainly how Roslyne Haigh felt when she chanced on images of the lost tombstone of her forebear Samuel Osborne on the Facebook page of Newcastle Family History Society. Roslyne, who lives in Kempsey, had been seriously researching her own family history for about six years when she chanced on the photographs.

She had previously visited the cathedral and, like so many others, had deplored the circumstances that led Newcastle City Council in the 1960s and ’70s to destroy so many of the grave markers. Many very old and important tombstones were broken up and removed, with just a relative handful left, mostly face-up to the weather, as a reminder of what was lost. Roslyne had seen the photograph the council had taken of the gravestone before it was broken up and removed. Such photos, now available on the council’s Hunter Photobank site, were a condition of the approval of the land-swap between the council and the Anglican church that led to the graveyard’s conversion to parkland. But according to Roslyne, it was when she saw the photo by Ron Morrison of the tombstone leaning against a pile of others with the cathedral in the background that she felt the “shivers up her spine” that set her on the trail of the lost stone.

Samuel Osborne’s gravestone had been among those earmarked for preservation since it was in relatively good condition. But somehow that didn’t happen and the stone was broken into pieces and removed, along with many others that had been in good condition, to be used in retaining walls and landscaping features at Blackbutt Reserve, a bushland park at Kotara.

Historian Dave Hughes has made a study of the lost gravestones and some years ago tried hard to locate any identifiable fragments at Blackbutt. One of the few pieces he found and photographed was a remnant of the tombstone of Samuel Osborne. Although it doesn’t contain Samuel’s name, it is unmistakeably the part that bears the sentence: “In the midst of life we are in death”.

When Roslyne contacted me to ask if the fragment was still able to be found I got in touch with Dave, who now lives in Tasmania. He provided a rough sketch of the location as he could best recall and, fortunately, his memory proved reliable. Buoyed by the news that the piece of stone was still in place as part of a short retaining wall alongside a pathway from Blackbutt’s Carnley Avenue section, Roslyne and her husband Richard drove down from Kempsey to make a pilgrimage.

It may seem odd that such a fragment would have a significant emotional meaning but it certainly did for Roslyne, who filled me in on some details of Samuel’s life.

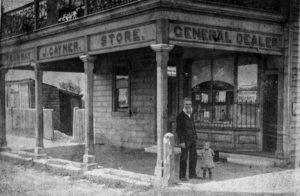

Samuel Osborne arrived in Australia from Somersetshire, England, at the age of 23 as an assisted immigrant aboard the ship Fitzjames on July 28, 1858. He was accompanied by his wife Susan, 22, and the couple’s two-month-old son Samuel. Samuel snr was listed on the ship’s manifest as a quarryman, but six years later when he met his death he was a “dealer” who lived at or worked from Honeysuckle Point in Newcastle and plied some form of trade on the Hunter River.

It was on July 26, 1864, when Samuel was attempting to “set the sprit” on a boat at Seaham that he was knocked into the river and drowned. The two people aboard the boat were an old man and a very young girl who said he appeared to have hit his head as he fell. The river was dragged and Raymond Terrace police recovered the body that night. An inquest found his death was accidental. He was described as “a sober industrious man” and he left behind his widow Susan and four children.

Susan remarried and moved to the Taree district, leaving plenty of descendants including Roslyne.

According to Roslyne, she felt a powerful call when she saw the photo of her great-great-grandfather’s tombstone with the cathedral looming behind it. “Something was telling me to follow this through,” she said. “And going through and linking that photo with the third photo of the fragment at Blackbutt . . . I lost it because back there it was deemed to be repairable and now it’s not, it’s lost. To me this fragment is still part of him”.

When Samuel’s widow, Susan, moved to the Taree area and married into the Gill family, she was her new husband’s third wife. When he died he chose to be buried with his first wife, so Susan now lies alone at Taree.

POSTSCRIPT: In early 2024 Roslyne managed to have the fragment of Samuel’s ruined tombstone placed with the grave of his son at East Kempsey Cemetery, as pictured below.