This is an excerpt from our book, The Hunter Region in The Great War.

After the slaughter of Fromelles, where the Australian 5th Division had been critically weakened in a failed “feint”, the main British attack on the Somme awaited an Australian contribution. The British attack had gotten off to a bad start. The artillery bombardment before the infantry attack didn’t do the damage the British generals had hoped for, so casualties on the British side were extremely heavy. About 20,000 died on the first day, with many more wounded. But the British, committed to trying to take pressure off the French – who had been suffering horrendous losses from German artillery at Verdun – weren’t ready to give up.

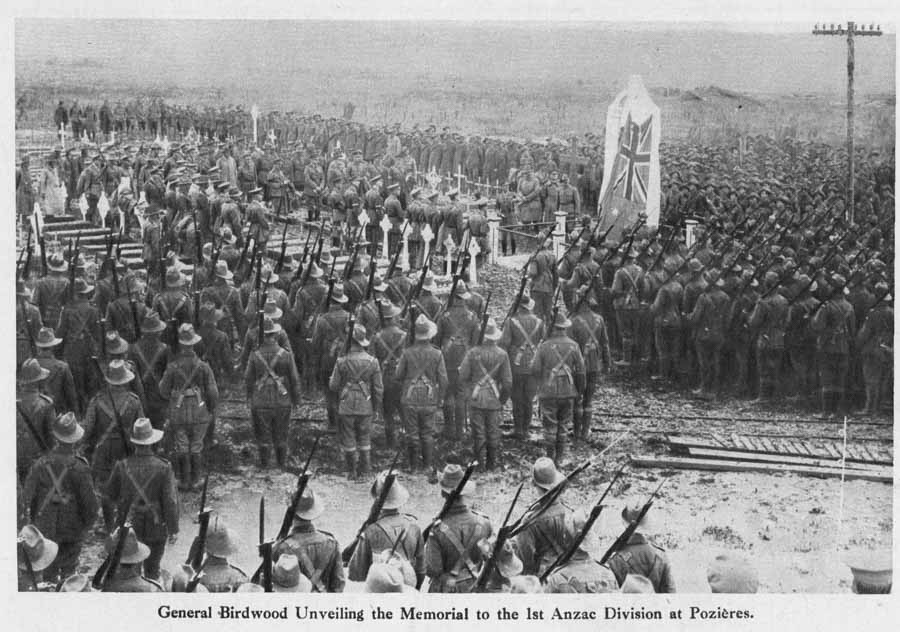

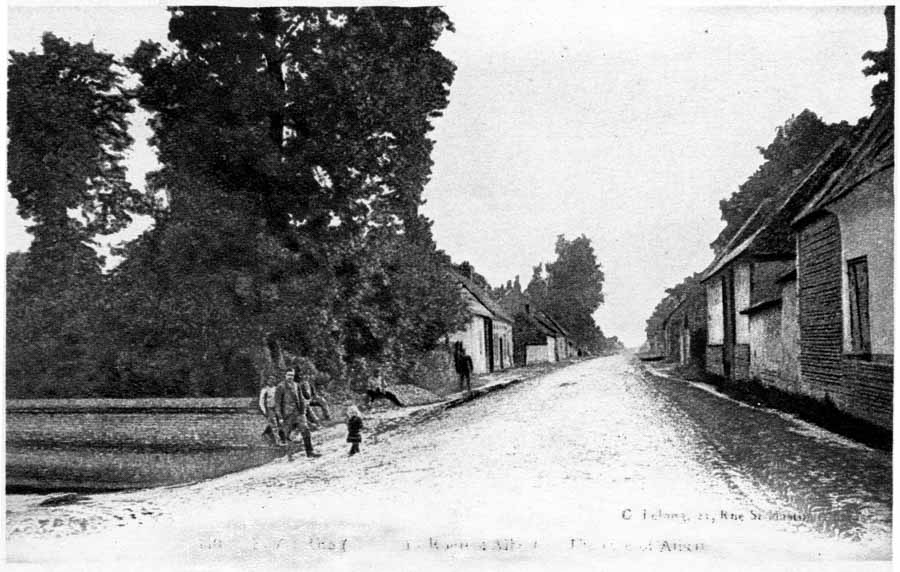

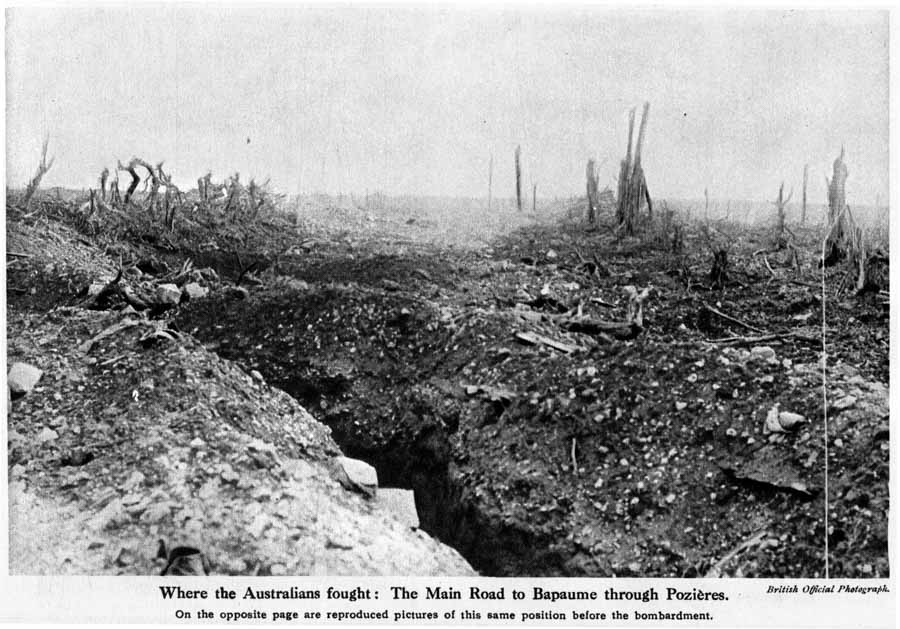

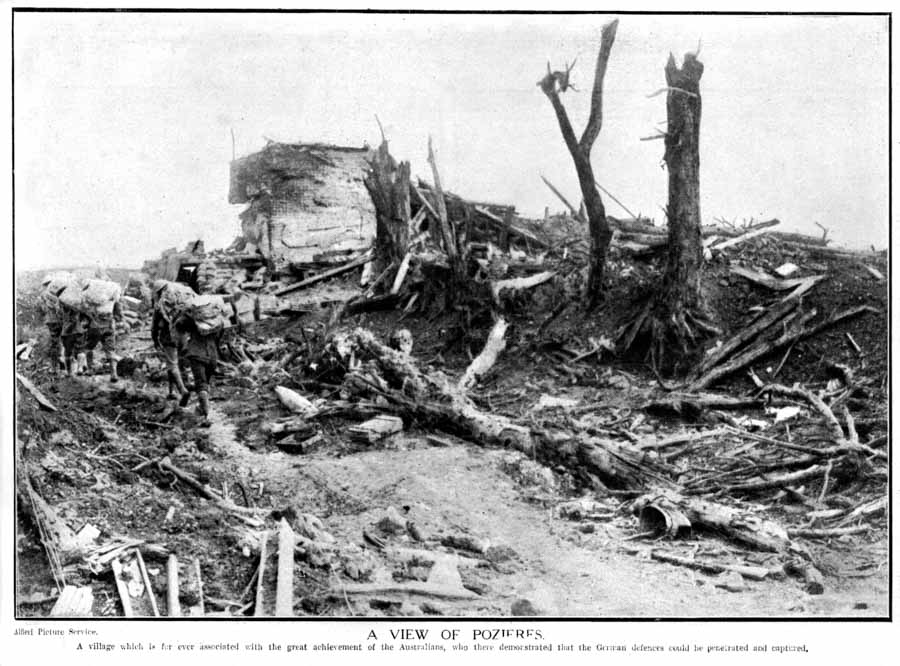

Australia’s turn to participate in the costly exercise came in the area around the village of Pozieres, on July 23, 1916. This time three Australian divisions – the 1st, 2nd and 4th – were under the ultimate command of the British general Hubert Gough, a commander with a reputation for poor preparation. Pozieres was chosen as an objective because it occupied a high point and commanded views of the surrounding country. The British hoped that taking Pozieres would enable them to roll back the German lines. The British Fourth Army had made four unsuccessful attempts on the village before the Australians were sent in, and the village had been completely pulverised by artillery fire.

A British bombardment preceded the infantry attacks, as usual, and the Australians who charged the featureless rubble-pile that was once a village managed to secure it, with some difficulty. But because their success was isolated, the new occupants of the village became the focus of severe German counter-attacks and an artillery barrage of extreme ferocity.

At Pozieres the Australians endured the worst bombardment they encountered in the entire war, and the casualties were tremendous. Official Australian war historian Charles Bean, who witnessed the action at close quarters and considered himself lucky to escape with his life, likened the battle to a “ghastly giant mincing machine”. The men, he wrote:

have to stay there while shell after huge shell descends with a shriek close beside them – each one an acute mental torture – each shrieking tearing crash bringing a promise to each man – instantaneous – I will tear you into ghastly wounds – I will rend your flesh and pulp an arm or a leg – fling you half a gaping quivering man (like those that you see smashed around you one by one) to lie there rotting and blackening like all the things you saw by the awful roads, or in that sickening dusty crater.

In the fighting around Pozières the 1st Australian Division lost 7700 men, the 2nd Australian Division had 8100 casualties and the 4th Australian Division lost 7100 men. Joe Maxwell’s platoon, as an example, went from 60 men to four. In his book, he described witnessing the bombardment from behind the lines.

Rolling, brownish-black smoke-clouds eddied and swirled around us. The acrid tang of explosive hung heavy in the air. It was ripped again and again by the quick yellow and red flash of bursting shrapnel. Higher and higher rose the thunder of the guns, the plumes of yellow multiplied, the smoke swirled faster, and the reek of explosives fell like the stench of death. Could anyone survive in this vast open-air slaughterhouse? Into the flailing wind of steel we stumbled. Men flopped into holes and dropped on the slopes of ridges merging with the grey-brown of the soil.

Melbourne journalist Lieutenant John A. Raws wrote the following graphic account of Pozieres:

We lay down terror-stricken along a bank. The shelling was awful. We eventually found our way to the right spot out in no-man’s-land. Our leader was shot before we arrived and the strain had sent two other officers mad. I and another new officer took charge and dug the trench. We were shot at all the time … the wounded and killed had to be thrown to one side. I refused to let any sound man help a wounded man; the sound had to dig. We dug on and finished amid a tornado of bursting shells. I was buried once and thrown down several times, buried with dead and dying. The ground was covered with bodies in all stages of decay and mutilation and I would, after struggling from the earth, pick a body by me to try and lift him out with me and find him a decayed corpse. I went up again the night and stayed up there. We were shelled to hell ceaselessly. X__ went mad and disappeared. There remained nothing but a charred mass of debris with bricks, stones, girders and bodies pounded to nothing. We are lousy, stinking, unshaven, sleepless. I have one puttee, a dead man’s helmet, another dead man’s bayonet. My tunic rotten with other men’s blood and partly spattered with a comrade’s brains.

Private Thorold Toll, son of Wickham alderman and businessman Albert F Toll, wrote home:

Since last writing to you I have gone through several of the most horrible days of my life. Our company had six killed and twenty odd wounded – 20 percent casualties. Our section officer was wounded in the leg as we were making our way up to the front line. He was directly between me and the bursting shell and only for his leg intervening it would have got me. The shellfire is awful and the saps are very shallow and filled with dead. People at home have not the faintest idea of what war is. If they got but one glance at things as they are it would be the greatest shock they ever had. Gallipoli fighting is not to be compared with here. Men who were on the peninsula the whole eight months agree that it is not, and men who have returned have seen nothing to approach the shell fire here.

[Private Toll was was captured at Riencourt on April 11, 1917 and made a prisoner of war. On May 1, 1917, he and three other prisoners were killed instantly when an Allied shell exploded nearby while they were unloading ammunition from a train.]

Private James Rogers wrote to his parents in Plattsburg:

Pozieres, the place we took, was one of the hardest places along the front. When we arrived in the firing line, which was merely a freshly-dug trench, there were no dugouts, etc, the Tommies, whom we relieved, having lately advanced to this point, facing a wood and the village of Pozieres. Dead were laying about in hundreds, both British and Germans, unburied. About five yards in front of me, towards the German trenches, five Tommies were lying dead, one still clutching his rifle. I suppose they were mowed down by machine guns after leaving their trenches. The place I might tell you is like a sea with shell holes. There must be hundreds of thousands of shells fired about the vicinity of Pozieres. Before we advanced 1700 guns opened up. Some of the shell holes are 20ft deep. We also used 102lb trench mortars.

We charged at 12.25am on the Sunday morning, and took the first line OK. Our chaps were pretty free with the bayonets. All the Germans in the front line were killed. We dug ourselves in the shelled trench, waiting for a counter-attack. In the morning we were ordered out, where a company of Germans had dug themselves in on our left. We had to dig in the open, and were covered by our bombers, who kept the German heads down. We dug in OK. A few of us were sniped. All my mates were killed, I am sorry to say. One, while talking to me, was shot through the heart. After we dug in the brigade bombers and machine gunners soon put an end to Fritz, taking a good many prisoners. The next day Fritz’s artillery started to shell. They say it was as bad as Verdun. I myself alone came out of six. A lot were buried alive. The shells were like hailstones. All high explosives, 9.2in and 5.9. I was buried, and it will take some time before I am really myself again. One of these shells buries about 15ft, and throws stuff 400 yards away. They were awful. We were relieved after six days. All this time there was no sleep, work all the time. Our officers were good, without a doubt. Captain Cotton, a young chap from Maitland, was killed, also a few others, and I can assure you we miss them. We would have followed them anywhere.

Ben Champion was in the charge on Pozieres. His unit’s only experience of the front line had been a quiet area used as a “nursery” for green troops. The march on July 19 to the Pozieres battlefield opened his eyes:

We realised at last that we were in a war. The Northern sector to us was just a nursery to prepare the way for this. Heaps of used ammunition, shells and war litter of all kinds, broken rifles, equipment, guns, boxes of biscuits and ammunition were strewn everywhere. Soon we came to an area with the sickly smell of dead bodies, and half-buried men, mules and horses came into view. Here was war wastage properly. Germans and British mixed together, lying in all positions, and there wasn’t a man but thought more seriously of what was ahead. On across the late No Man’s Land, and we found what was once the village of Pozieres, but now a red brick rubble heap, to be opposite us some little distance away. The sector A Company took over was not a continuous trench, and after coming all the way we had, loaded like mules, dog tired and frightened, we had to turn to and dig our own line.

After a few days of being shelled by German guns, Champion waited for the word to attack:

On Sunday the 23rd, we hopped out of our trenches and formed up in our waves in No Man’s Land. The tension affected the men in different ways. I couldn’t stop urinating, and we were all anxious for the barrage to begin. When it did begin, it seemed as if the earth opened up with a crash. The ground shook and trembled, and the concussion made our ears ring. The mortars and large shells glowed red as they fell.

Champion’s company advanced, with severe losses, and began to dig in as they had been ordered, while other companies moved through and beyond them.

We lost all our officers, and soon we had NCOs and privates taking charge. The stretcher-bearers had a busy time, carrying back over the churned up soft ground. The countryside seemed changed – the shell fire had obliterated many landmarks and Pozieres itself was levelled more, if that was possible. We were being continually bombarded, the trenches caving in, and we were digging each other out all day long. Soon our beautiful trench was nothing but a wide ditch, each caving making it shallower and shallower. Men were going back wounded, and our garrison became thinner and thinner.

On July 26 – by Champion’s reckoning “our worst day” – his company was sent to help another unit:

Of course Fritz shelled us unmercifully, and charging over ground, and walking on the corpses of our AIF men gave us the creeps. We were relieved at last by a battalion of the second Brigade, and we straggled out to the chalk pit. What a mess of a battalion! We felt very sad, for by the look of it we had lost more than half of our men.

Before departing overseas, Champion and a mate had done a cycling tour from Liverpool camp to Krambach, on the Bucketts Way. The trip took them through Tarro, where he met young Frances Niland, the girl he would later marry. Ben wrote to his future father-in-law on August 3, 1916, describing things he would never include in letters to his beloved, whom he nicknamed “Frank”:

Once again I have come out of a scrap unscathed. This was some battle I can assure you and relief was never more welcome to the boys when it came on the sixth day.

For a few hours after the capture of P…. things were fairly quiet but Fritz became busy with his artillery and shells of all sizes from wiz-bangs to coal-boxes simply rained upon the captured positions.

Despite the serious predicament we were in we could not restrain from laughing at one another. We did not charge with overcoats and as the night was bitterly cold we soon slipped into the dead Germans’ overcoats and with their little round caps soon found ourselves comfortable for ½ hour when the beggars started to shell. It was continuous shelling during the six days in the trenches, none of us had more than one hour’s sleep. I was surprised to find, how in such emergency, sleep was not required, but we sure slept when out of danger. The gas shells caused us considerable alertness they burst with very little row indeed as some found out when it was too late. Tis cruel this awful war.

During our second charge the trenches under foot were springy, we understood, our comrades killed, more on top, no time to bury them. Arms, mutilations, by God it was awful. This is not war but wholesale slaughter, soft flesh pitted against steel and explosions. Rifles, equipment and dead Germans buried in the parapet, anything put there so as to give cover. Many men were buried by the big shells and nothing known about them.

Official war historian Bean saw the bombardment first-hand:

Suddenly there is a descending shriek, drawn out for a second or more, coming terrifyingly near; a crash far louder than the nearest thunder; a colossal thump to the earth which seems to move the whole world about an inch from its base; a scatter of flying bits and all sorts of under-noises, rustle of a flying wood splinter, whir of fragments, scatter of falling earth. Before it is half-finished another shriek exactly similar is coming through it. Another crash – apparently right on the crown of your head, as if the roof beams of the sky had been burst in. You can just hear, through the crash, the shriek of a third and fourth shell as they come tearing down the vault of heaven. A swifter shriek and something breaks like a glass bottle in front of the parapet, sending its fragments slithering low overhead. It bursts like a rainstorm, sheet upon sheet, smash, smash, smash, with one or two of the heavier shells punctuating the shower of the lighter ones. As the evening wears on the salvos become more frequent. All through the night they go on. The next morning the intervals are becoming even less. Occasionally the hurricane reaches such an intensity that there seems no interval at all. Towards dusk it swells in a wave heavier than any that has yet come. All through the second night the inferno lasts. In the grey dawn of the second day it increases in a manner almost unbelievable – the dust of it covers everything; it is quite impossible to see.

The Germans could not dislodge the Australians from Pozieres, but the dead were many, and the survivors deeply scarred. In the official history of the 4th Division’s 13th Battalion, The Fighting Thirteenth, author T.A. White described moving up to take over the line at Pozieres: “The passing through of the wearied 1st Division, after their fortnight up near Pozieres, was inspiring, if sad”.

Ben Champion saw things from the other side:

About 6pm news came through to move back, and a scarecrow mob marched through Albert.

We saw the 7th Brigade march in. They gave us a cheer, which I’m sure was more out of sympathy for our appearance than for anything we had done.

Many men were temporarily, or even permanently deranged by the sheer horror of it all. “Shell-shock” was common, and the scars of this battle stayed with many who survived the war for the rest of their lives.

Private Albert Avard wrote to his parents in Thornton from an English hospital, describing the symptoms:

I have been sent over here with several more cases for special treatment, as this is a special hospital for shell shock cases. My speech has not improved much this last ten weeks. There are about fifty cases here, and you can see shell shock in all its forms. Some, like myself, have a trouble to speak; some cannot speak at all. Some cannot hear; others have twitchings in the face, and are in a constant shake all over. Anyhow, the cure is a matter of time generally, as a lot of cases end as suddenly as they start, through some excitement or such like. I think we will have to learn the deaf and dumb alphabet. There is only one thing I am sorry about: I never had a few months go at Fritz. Our battalion got a pretty good doing at Pozieres. The night we went in there were about 1100 men in it, and they came out in five days time with 120; but still, considering the nature of the fighting, a small percentage was killed. Had rather a rough ride across the channel. Our train left Dover at 12 noon on Saturday. There were about 500 cases on it.

The Germans had things just as bad. To his future father-in-law at Tarro, young Ben Champion wrote:

The Germans my platoon captured were typical, some young tall fair eyes and light straw coloured hair. All looked knocked-up. We also captured a doctor, although he carried firearms we didn’t kill him for he was very careful in handling our wounded and many a man in the first line of trenches owes his life to the treatment of this doctor.

Champion described another episode:

One of the Pioneer battalion men was found 30 hours after he was hit, in a shell hole. In the huge hole 20 feet square and deep was a live German. The Pioneer man said the German had bandaged him up and taken care of him since he was hit. When our stretcher bearers (wonderful men) came along this German would insist on taking his turn at carrying (no joke when high explosive shrapnel is flying about). The German and Australian swapped addresses. And as many of us as could shook hands with the German much to his surprise. But we all thought he was a good man.

Champion predicted that Germany would lose the war.

The German star is setting and the “Day” not the day to which they dreamt but the day of the allies is coming when they shall be driven right over the Rhine defences into Berlin and will have the pleasure of seeing their own land laid waste by us the same as ruthless slaughter of life, land and stock was done by them. Of course the losses will be heavy but must be borne if Germany is to be put in the one place she has earned and forced to keep there.