ON the night of May 22, 1922, a seaman by the name of West had a bad dream. West was a fireman aboard the NSW collier Meeinderry, due to leave Sydney next day for its regular run to Newcastle. The elderly steamer – built in 1884 – was a veteran of Australian coastal shipping, originally a passenger ship but converted for the coal trade and operated since 1919 by R.W. Miller. The previous year Millers had tried to sell the old ship to a group interested in using it in a Norfolk Island trading enterprise but the sale fell through, leaving an acrimonious court case in its wake.

In his dream, West saw the big liner Murama “turn turtle” and sink. When he woke he told his shipmates and declared he wouldn’t go on the trip to Newcastle that day. They talked him out of his decision, however, and the ship made its routine run to the coal port where it loaded and prepared for the trip back to Sydney. It was Monday, May 23, about 10.50pm, when the Meeinderry left Newcastle again. West, like other members of the eight-man crew, went below to his bunk and was quickly asleep.

The ship had only got as far as Redhead at about 12.15am when disaster inexplicably struck. Another collier, the much bigger Wallsend, was on its way north. The two ships sighted each other and made to pass. But somehow, something went wrong and the Wallsend ploughed into the Meeinderry’s starboard side, carving a hole about a metre square and sending torrents of water into the smaller ship. An inquiry later put the blame on allegedly faulty steering gear on the Meeinderry, with the mate declaring it jammed as he tried to turn from the Wallsend’s path. The inquiry was frustrated, however, by conflicting evidence given by men aboard each ship, with one claiming they were trying to pass on the starboard and the other claiming they were passing to port. It was acknowledged that somebody was lying, but in the end the allegedly faulty steering gear took the blame.

After the collision the undamaged Wallsend stood by, ready to take off the crew of the crippled Meeinderry. But Captain Peterson of the Meeinderry opted to try to save the ship. The crew took to the pumps, struggled to plug the massive hole and headed back towards Newcastle as fast as they could steam, with the Wallsend keeping pace and ready to take off the crew if necessary. The hole was in the ship’s stern quarter, so the rear compartment rapidly filled and the ship settled low in the stern. But the watertight bulkhead – though it sprang a leak – kept the flow manageable by the crew’s strenuous pumping. With frantic efforts the crew managed to nurse the Meeinderry back to Nobbys Breakwater before the water finally gained enough to put out the fires. The ship had just enough steam in its boiler to enter the harbour at about 2.30am – with the pilot vessel Ajax standing by – before it sank in the wave trap and settled to the bottom.

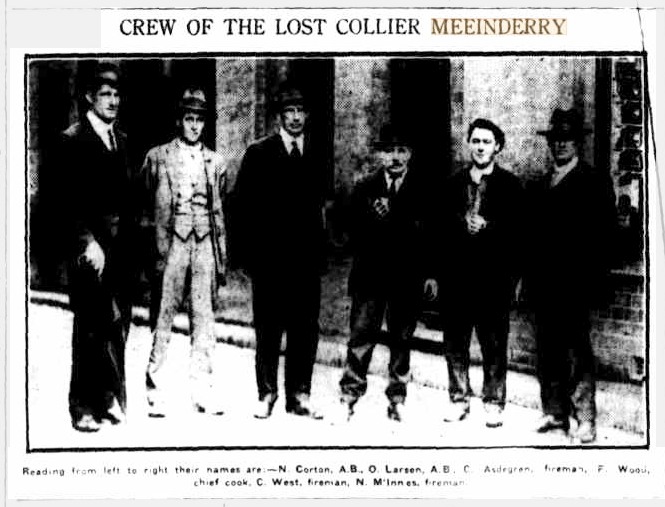

The crew members got ashore in the ship’s boats and were put up at the Sailors’ Home, where they gave interviews to the press before being returned to their homes in Sydney.

The ship sat, stuck fast in the sand, for a month, resisting refloating attempts by salvage teams from Newcastle’s Walsh Island Dockyard. When the dockyard conceded defeat in mid-June – citing bad weather as the reason for its failure – the ship’s owners called in Sydney-based marine diver A. A. Albert on the basis of no payment without success. Albert succeeded where the dockyard had failed. He removed the ship’s internal bulkheads, patched the holes in the hull and pumped it full of air until it floated and could be towed to a dolphin berth at Stockton. It was later slipped, but never repaired. Interviewed after the successful salvage, Albert said he had been approached about the job by the insurers the day after the sinking, but was then told the dockyard had been given the job. He declared that he could have had the ship refloated within 48 hours had he been given the job at the time, adding that damage to the mast and superstructure would also have been avoided. The ship had sunk another metre into the sand during the month that had elapsed, he said, adding still further to the difficulty.

According to a letter in The Newcastle Morning Herald on June 21, 1923, Walsh Island Dockyard had run up expenses of £2500 during its failed attempts “with most wonderful gear and a number of men”. It was said that the hulk – worth less than £500 – was given to the dockyard as settlement of its bill, while “the work of raising this vessel was afterwards carried out by a local firm, three men and a boy . . . at a total cost of £250”. So ended the career of the Meeinderry, broken up at Walsh Island, while the excess costs were presumably met from the public purse.

Greg, great article. Thank you for documenting the loss of the Meeinderry. I found your article while researching a family connection to the Meeinderry. My Great Great Uncle, Robert Henderson Nichol, was for a time the Chief Officer or Mate of the Meeinderry while it was part of the Tasmanian/Victorian port trades. Sadly, Robert died on board the ship in August 1898 while it was berthed at Melbourne.

Thanks Nicholas. Glad you liked the blog post.