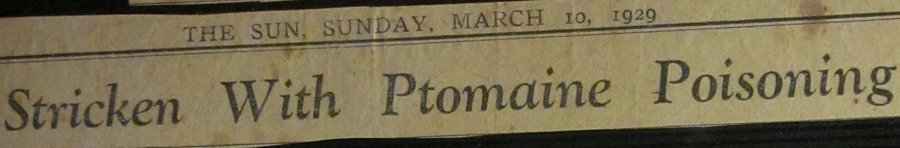

Ever had ptomaine poisoning? Ever heard of it? I hadn’t until I was loaned a scrapbook which included newspaper clippings from 1929 reporting the hospitalization in Newcastle of more than 40 children suffering from this dread ailment.

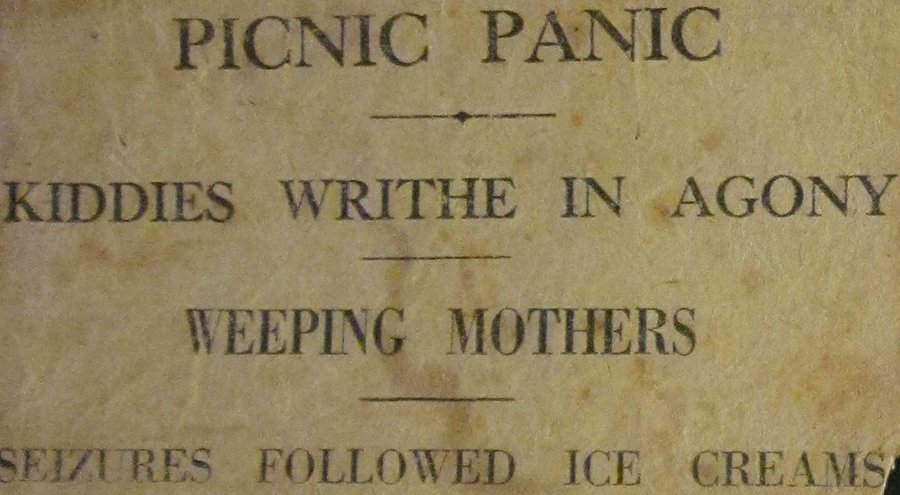

It was March 10, 1929, the day of Mayfield Baptist Church’s annual picnic. About 150 children, with various adults in attendance, had traipsed off to “Beresford” [Beresfield?] at about 9am, spending their morning at various games. They had lunch, some picnic sports and then were called to the canteens for ice cream.

Not long after the ice cream, one youngster fell to the ground and started writhing and groaning in pain. Over-indulgence, the adults assumed, until more and more of the kids – and some adults – also keeled over and started squirming and moaning. Clearly this was serious. To quote a press report: “with dramatic suddenness, one little mite fell writhing to the ground, and while concerned parents were rushing to its aid others began to fall everywhere. Horrified, the picnickers began to rush from one to another, and soon pandemonium had broken loose in the picnic grounds. Children began to cry, and distorted faces and writhing forms told a story of excruciating pain”.

Panicking parents flocked to use whatever nearby telephones they could find and soon a relay of ambulances was carting more than 40 cases to Newcastle Hospital where 15 were admitted, some in a serious condition. Those hospitalized were Eileen Powell, 12, Kevin Betts, 2, Alan Dunbar, 3, Herbert Johnson, 6, Mary Jacobs, 13, Thelma Beauvais, 12, Alice Cummings, 42, Fred Cummings, 7, Leslie Cummings, 6, Thomas Robson, 3, Nerida [or Merva] Lister, 5, Dorothy Curtis, 6, John Sly, 2, Emily Sly, 27 and Melba Watts, 12. All were from Mayfield addresses. Leslie Cummings was apparently the most serious case but he fortunately recovered.

The incident was blamed on “ptomaine poisoning” which, it turns out, is an old-fashioned name for food poisoning in general. Even in those days food poisoning was not well-understood and the various forms of bacteria that cause it weren’t commonly recognized. “Ptomaine” was a catch-all term and it was a widely feared fact of life in days when refrigeration was uncommon and food preparation was often less than perfectly hygienic. Tinned meats, apparently, were often blamed for attacks which could sometimes be fatal.

In the case described here ice cream was initially blamed, since it was just after eating that dessert that most of the victims started showing symptoms. But a medical officer at the hospital declared the culprit was almost certainly the meat that had been used on the sandwiches eaten earlier in the day.

Ptomaine is a frightening-sounding name, to my ears at least, but maybe no more so than many other old-fashioned names for diseases and ailments, some of them not commonly seen these days.

Scurvy springs readily to mind, perhaps because I’ve just been reading the memoirs of a rich 18th century Englishman, William Hickey, whose account of a voyage from India in 1780 includes a description of the effect of scurvy on the crew of the ship in which he was travelling. Scurvy, as was realised even then, is a disease of malnutrition, famously kept at bay by some more intelligent captains by the provision of lime juice. Hickey writes that: “In three days we lost six of the hands from the scurvy, all of whom died suddenly, three of them dropping to rise no more whilst at the helm. Within the following twelve days our loss amounted to thirty-three. Captain Gore, terrified beyond measure at the forlorn state we were in, carried his weakness so far that at last he would not receive the sick list from the doctor, also forbidding any tolling of the bell as was customary previous to performing the funeral service upon a corpse being committed to the deep.” Soon only 16 hands were left to work the ship, albeit in weak condition. They made it to port by pressing some French officers – aboard as prisoners of war – into voluntary service.

So much for scurvy, although I might mention that when I was young my parents used to tell me I’d get that dread disease unless I ate my pumpkin.

Scurvy, dropsy and quinsy

What about dropsy? And quinsy?

You never hear of anybody getting those old-fashioned diseases anymore. Nowadays we’re more likely to call them oedema and tonsillitis, names that lack that old folksy ring. Colourful old enemies like scarlet fever, yellow fever, the black plague and green sickness are seldom seen these days, in the wealthy western world at least.

Measles, mumps and chicken pox were common in my youth. And what fitting names they had. What could be more measly than measles? I had mumps as a child and can confirm they are lumps that make you mumble. My case of chicken pox was so severe (I had those itchy little blisters in places you couldn’t begin to imagine) that I reckon I looked like a scrawny just-plucked chook.

Rickets, back in the day, was a soft-bone disease of young people, caused by Vitamin D deficiency. These days a shaky building might be described as rickety, without a thought for the origin of the word.

We still meet the odd victim of gout, but I doubt you’ve heard anybody complaining about their grippe, which is really just the flu. Shingles is still around (and yes, the outward signs of those screaming nerves can look a bit like radiant roof-tiles rippling down your side), but scrofula has gone the way of most other forms of consumption [TB], including the galloping kind. Also known as “the king’s evil”, scrofula apparently gave you a really lumpy neck.

Lockjaw was an old name for tetanus, I think, but unless the anti-vaccination folk make a lot more headway that one seems to be a thing of the past altogether.

Scrumpox was a kind of skin disease. Scotomy was dizziness and dimness of sight and the pain once called “screws” would today be bundled under the heading of rheumatism.

The stomach upset caused by spoiled milk was called “summer complaint”, presumably because it was warm weather that caused the trouble. Pneumonia was “winter fever”. A fever that lasted a day was “diary fever”, and a skin disease caused by mites in sugar or flour was called “grocer’s itch”. Swollen veins after childbirth were called “milk leg”. You didn’t get sciatica, you got “bone shave”. You didn’t get dengue fever, you got “breakbone”. A coldsore was a “canker”, epilepsy was “falling sickness” and concussion was “commotion”.

In those days you could have a flux of humour and nobody would think twice. If you had bad blood or French pox though, people would start to talk (treatment for syphilis was pretty extreme back then). Mormal was another name for gangrene.

When I was a kid my parents warned me that if I ran around with no shoes on in cold weather I’d get chilblains. I’ve never seen a chilblain, but even the word seems painful. I know my grandmother hated her bunions and I wished for her sake they’d go away, but I was always very impressed by how much they looked like their name. Like bulging onions on your foot.

They had a disease too, for writers who spent too long scribbling: scrivener’s palsy by name, which is the last thing on earth I’d want to have.

My Grandmother, Emily McGregor, constantly reminded us in the 1940’s in Newcastle of the danger of “Potamine” poisoning. What it was and from whence it came we had no idea, but it sounded dire.