The recent appearance of two clusters of tuberculosis disease in Australia is a reminder that this deadly old foe has not been eradicated. Indeed, it is estimated that about a quarter of the world’s population harbours the TB bacteria, with new variants emerging that are harder to treat. No widely effective vaccine is available.

Growing up in the suburb of Rankin Park, Newcastle, NSW, I was aware that there was – a few kilometres through the bushland near my home – a “chest hospital”. That’s what my father called it, whenever we drove past. It was explained to me that this was a place for people with a nasty disease who needed special care. The disease, I was told, was called “TB”, or “consumption”. I have a recollection of Dad referring to “galloping consumption”, which I gathered meant a case in which the disease progressed rapidly to its fatal end. The image that the word “consumption” summoned to my mind’s eye was of a body being consumed from within by the hungry ailment.

Later I learned that TB stood for tuberculosis and that it seemed to be an affliction of older people, perhaps especially ex-soldiers who had served overseas. In time I learnt still more, though much of this learning was misleading, inaccurate or untrue. The biggest half-truth I learned about tuberculosis was that it was a thing of the past and no longer a cause for concern. It was, I supposed, like polio and smallpox, a former scourge – now eradicated – that I was fortunate not to have to think about.

For years “consumption” was little more to me than a motif used by film-makers in historical dramas. You knew, as soon as a character surreptitiously coughed into their handkerchief and the camera zoomed in on the little gob of blood, that they were for the high-jump pretty soon. Galloping consumption was about to take them away.

When I was in my thirties I encountered TB again, unexpectedly. An elderly friend, whom I visited from time to time, had become paralysed from the waist down and was taken to hospital. Apparently the cause was “tubercular lesions” on his spine. I was told that tuberculosis could enter the body and lie dormant for years before breaking out into symptomatic disease. Also, that it needn’t always be a disease of the lungs. Presumably my old acquaintance had been exposed long ago and the bacteria had been latent in his body, unsuspected, all that time. This was surprising and disconcerting at the time, but I soon forgot about it.

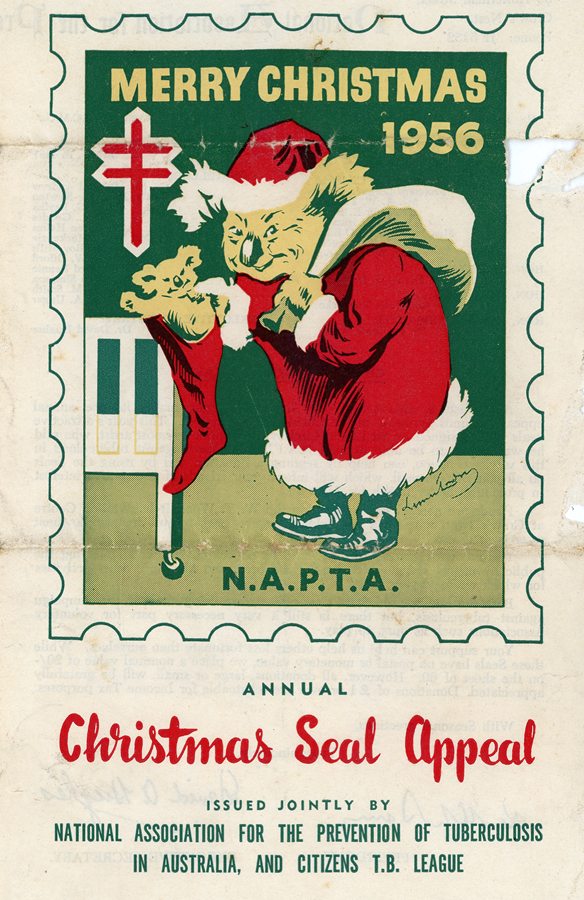

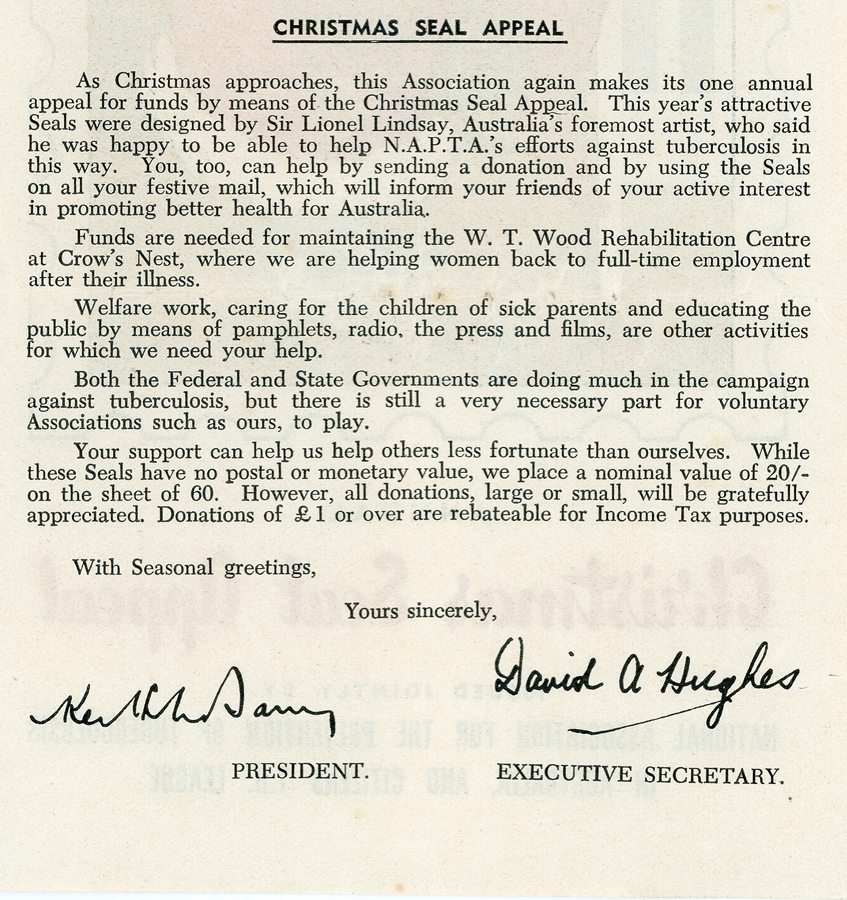

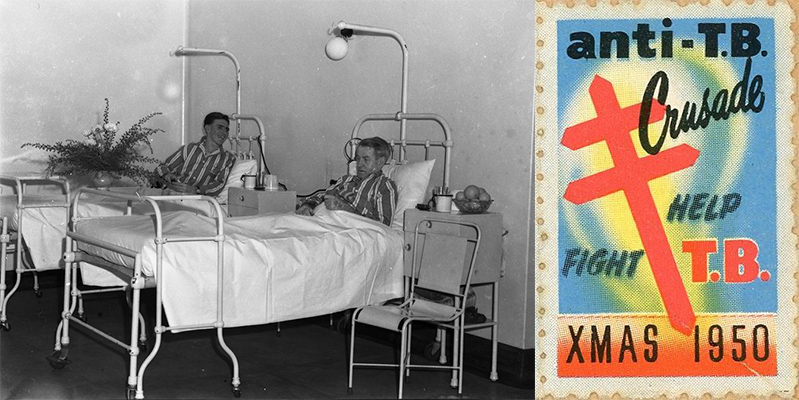

Some of the anti-TB “cinderellas” in my collection of ephemera.

TB came back to mind recently when I was thumbing through some old letters, the envelopes of which bore stickers raising money to fight the disease. The reminder that this appalling disease was, not so long ago, a major health issue for mainstream middle-class white Australians like me, prompted me to try to learn a little more about it. I almost wish I hadn’t made the effort, given the disconcerting facts I found.

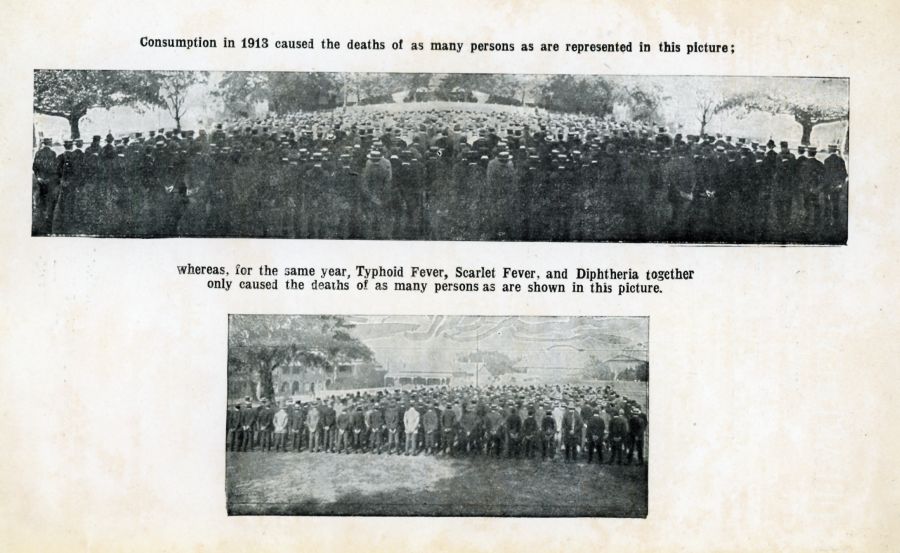

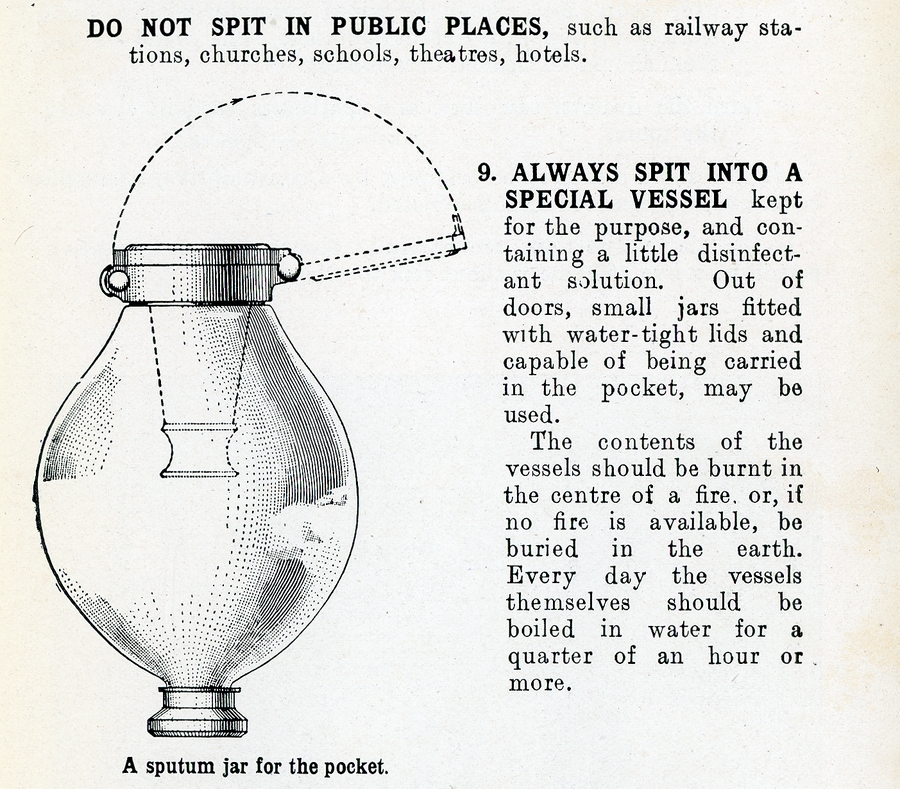

Tuberculosis has been a scourge of humanity – and other species including cattle – for thousands of years. Apparently traces of TB have been found in Egyptian mummies. In Europe from the 1600s to the 1800s TB caused 25 per cent of all deaths and by the late 1800s – before the cause of the disease was discovered – it was still killing about one in seven people in western countries. Up until that time a diagnosis of TB was considered a death sentence, albeit sometimes quite a slow one. Since 1882 when scientist Robert Koch discovered the bacteria that causes TB, much has been learnt about it. The bacteria divide very slowly – about once a day – compared to once every 20 minutes for some other types. They have a coating that protects them from the human body’s macrophage immune cells, which swallow the bacteria and try to destroy them. Instead of being destroyed, they divide inside the macrophages and eventually burst them. The body tries to isolate the damage and often fights the infection to a standstill. Some people may die of other causes with the bacteria still latent in their bodies, but others experience symptoms when the bacteria breaks the stalemate and multiplies massively, overwhelming the immune defenses completely. At this point the disease becomes transmissible via droplets coughed out of the infected lungs.

There is one vaccine in use, but it isn’t very effective so is only used in high-risk parts of the world. Antibiotic treatments have been effective, but come with a range of severe possible side-effects that mean many patients don’t complete their treatment, a factor that feeds into the increase in antibiotic resistance that is making TB harder and harder to deal with.

It’s disturbing to consider the steady resurgence of a deadly disease that was once one of Australia’s leading killers of human beings. In the early 20th century TB was Australia’s top killer of women and the second-top killer of men. Sporadic efforts at control and treatment since then achieved good results, reducing the death rate enormously. In the Newcastle area in the late 1940s local health authorities co-operated with the Red Cross organisation to convert a World War 2 emergency hospital that had been built at Rankin Park into a specialist “chest hospital” for TB patients. It actually took years to get the hospital open, apparently due to funding issues and staff shortages (some things never change!). It was 1943 when the State Government announced that the hurriedly built hospital would be reserved for TB patients, but the doors didn’t open on the facility until 1947, and that was only after the Red Cross provided help.

There were other chest hospitals around Australia. But in Newcastle, hospital board member the Rev. A.R. McVittie felt troubled by the term and asked that the hospital instead be named for the board chairman, A. A. Rankin. The reverend said the expression “chest hospital” was “undesirable and too suggestive”. His sensitivity was respected and the name “Rankin Park Hospital” was adopted.

The war on TB was taken very seriously by many Australians, and the National Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis in Australia (NAPTA) undertook large-scale fund-raising. One of its key methods was the issue of the stamp-like stickers I noted earlier in this article. (Incidentally, stamp collectors call these and similar non-postal stickers “cinderellas” and they are moderately sought-after.)

By the 1970s it seems that fewer and fewer of Rankin Park’s beds were needed for TB patients. A combination of better living standards and better treatments had reduced the impact of the disease, Unfortunately, however, it has not gone away and the absolute number of cases in Australia has been rising, partly due to inadequate healthcare in remote Indigenous communities, high immigration from countries with endemic TB problems and perhaps a degree of complacency.

Who knows? Perhaps if current trends continue we’ll be seeing the “Fight TB” stickers again.

In 1966 I was a resident at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney. The TB patients were usually fond of a drink, despite the incompatibility with the drug treatment. There was a small hotel (“The Wedge”, because of its shape) behind the hospital. It was easy to pick a TB patient in the bar, – the long overcoat with the pyjama trousers showing gave them away.

I remember mobile chest x-ray units for TB screening coming to Singleton (my boyhood home town) in the 1960’s. They were in the form of a large caravan. The screening was for adults, but I can’t remember if it was compulsory.

Hi Greg, as always you have come up with a most interesting topic to ponder. Researching my great uncle William Moses, a WW1 returned soldier , his death certificate stated he died at Waratah. In fact The Infectious Diseases Hospital. The location of which I don’t know. Probably the IDH was a forerunner to what I knew as the TB hospital at Rankin Park.

Reading your article was a bit scary where it mentioned treatment and side effects.

In March of this year after being treated for a prolonged cough following Covid I sought a second opinion from a specialist in Sydney. He washed my lungs and after 5 weeks had grown a bacteria from the inside of my lungs. Akin to TB. That bit was scary enough. Non contagious though but similar structure. Known as MAC for short and is water borne. Somewhere recently I have injested water into my lungs containing this bacteria MAC. The treatment is a cocktail of 3 antibiotics – ghastly and leaves symptoms not unlike chemo treatment. Weekly blood tests to monitor side effects. Treatment for 12 months and curable. That’s the good bit.

I heard stories from Gran about her uncle who came back from the war in a bad state of health- never was the same she said. TB took him out eventually, long suffering and debilitating and hard work for his sister who nursed him.

We must be grateful for modern medicine and private health cover.

Best wishes,

Jan