Rob the Ranter first crossed my path 30 years ago. That was when my attention was drawn by the then archivist at the University of Newcastle, Denis Rowe, to the existence of an interesting three-part serial article that had been published in The Newcastle Chronicle in 1862.

The article was titled Reminiscences of a Three-month sojourn in Newcastle, and was written by an anonymous figure who used the pen-name “Rob the Ranter”. Impressed by the content of the piece, I persuaded the editor ofThe Newcastle Herald to re-publish an edited version – again in three parts – across three Saturdays in July 1993.

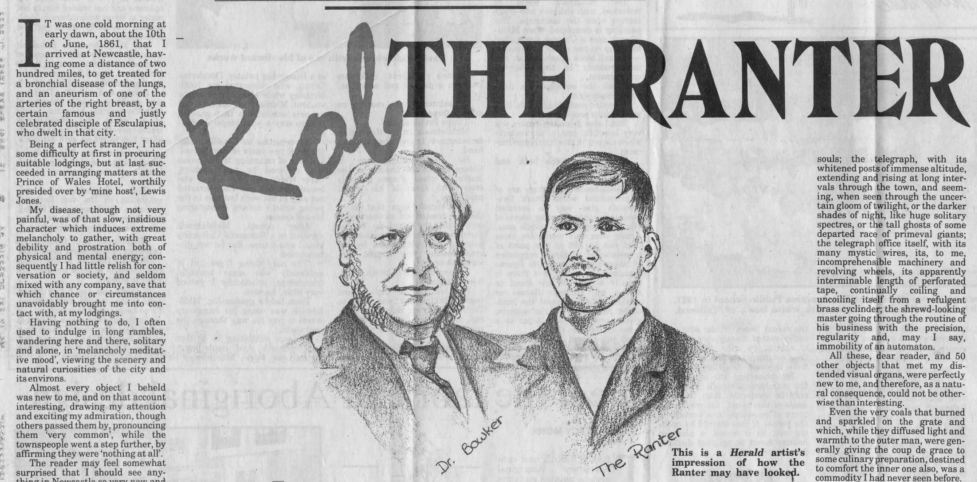

I was impressed by the article because of its atmospheric descriptions of aspects of Newcastle life in 1861. While he didn’t give his name, the author revealed that he was born in England and had been living in Western NSW. He came to Newcastle, he wrote, to consult a well-known medical practitioner, Dr Bowker, about some respiratory complaints.

No sooner had the first article appeared in The Herald than the identity of Rob the Ranter was established.

My old friend and community historian, the late Dulcie Hartley, consulted shipping records and found that the family had come from Ayrshire, that Rob’s father John was a farm labourer and his mother Marian was a milkmaid. Dulcie also found that John Stevenson paid £176 in 1864 for a 160-acre property at Dinnykimine, on the Castlereagh River, past Cassilis and Coolah.

Later, Ray Stevenson, of “Byrbank”, Tambar Springs, got in touch to say that Rob the Ranter was his great uncle, better known in the Coolah district as “Bob the Poet”. Bob had come to Australia with his family in 1838, aged three, aboard the ship Coromandel and his family settled near Coolah.

Robert Stevenson fancied himself a poet and storyteller, and had numerous works published in country newspapers including the Mudgee Liberal and the Bligh Watchman and Coonabarrabran Gazette. He married Martha Brooks in 1863 and the couple had 13 children. He died at a place called “Old Mollyan” on February 16, 1887, aged 52. His last known poem was published in 1885 but his works seem to have been well-regarded in his own district and continued to appear in newspaper columns here and there long after his death.

When “Rob” arrived in Newcastle in 1861 he was still single and aged 26. He was apparently much troubled with his health and described symptoms that sound rather like tuberculosis.

Why he chose the pen-name “Rob the Ranter” isn’t completely clear. That name had been in use since at least the 1600s, when Scottish poet Francis Sempill wrote his poem Maggie Lauder, in which a pretty woman was courted by a far-famed exponent of the bagpipes who went by the name of Rob the Ranter. Ranters, it can be noted, are said to have been a dissenting religious sect, much in favour of the idea that people don’t need preachers to dictate the terms of morality. In line with that idea, the poem’s Maggie was a married woman, a fact that didn’t stop the amorous piper from making his musical advances. Nor did it dissuade the fair wife from suggesting Rob could look her up anytime he came to Anster Fair. Many believe the poem is actually an exercise in extended raunchy double entendre, and it can definitely be read that way. It has survived in memory even today, perhaps thanks to its association with a catchy tune.

Rob the Ranter was further immortalised in literature when a later poet, William Tennant, wrote Anster Fair, a long poem about the imagined courtship between Rob and Maggie. Finally, more than one ship has borne the name Rob the Ranter.

At any rate, our own Bob the Poet, aka Rob the Ranter, makes it known in his rambling narrative of his time in Newcastle that he had a keen eye for the ladies. Perhaps he believed his rhyming efforts would make him as irresistible as skilled bagpipe work allegedly made the original Rob two centuries before. Some readers of The Chronicle who sampled his three-part article made it clear they believed the name was apt, but not for any reason Rob would have appreciated.

Rob arrived for his medical consultation in Newcastle in time to find the town in the throes of an unusually severe disturbance in the coal industry, the latest round of a long-running battle between miners and the four major coal companies operating at that time. The Ranter, who describes his impressions of a visit to The Tunnel coalmine at Glenrock, noted that the ruinous strikes were a general topic of conversation. Also commonly under dicussion at the time were the recent “calamitous floods at Maitland”.

Well established as a coaling port, Newcastle played host to scores of ships, powered by both sail and steam. It was

still a relatively small town with a population of about 8000. It had recently been incorporated as a municipality and had elected James Hannell as its first mayor. Under Hannell some steps were being taken to improve Newcastle’s streets, which the Ranter mercilessly criticised. The telegraph line from Sydney, another Ranter favourite, had just been erected.

In between consultations with his doctor, the Ranter journeyed out from his accommodation at the Prince

of Wales Hotel, wandering the city, the harbour and the cliff above the beaches.

His writing style was verbose, even for those times, and he was prone to long-winded digressions of all sorts that

led to some heated letters being written against him in The Chronicle, the editor of which published a disclaimer, stating that: “We are not to be considered as identifying ourselves with the opinions expressed by correspondents, for even while our views may be diametrically opposed to theirs, we are always willing to give insertion to any communication, expressed in terms of intelligence and moderation”.

Correspondents complained that the Ranter’s apparent wonderment at commonplace things and events was out of place. “Though our daily occupations and appliance of everyday life have awakened surprise in his mind, would it

not have been better to have kept them to himself, or told them to those equally ignorant with himself, than to fill your columns with things that are all-known?” asked one irate letter writer.

Another ironically suggested that the town’s people listen “to one who can set your action and your city before

the eyes of generations yet unborn by writing things that you already know”.

It is Rob the Ranter’s recording of the commonplace that makes his reminiscences interesting today. Raised in the bush from his early years the “big smoke” of the Newcastle “coalopolis” was full of surprises for him. Though not

a detailed account, and eccentrically selective in its focus, his series of articles give an unusual glimpse of the Newcastle of 160 years ago.

His descriptions of the dreadful sandy streets, the busy harbour, the filthy air and the people he met are certainly memorable, and his account of a trip through the mine tunnel at Merewether is also interesting. Hardly less entertaining are his tales of mishaps and misadventures associated with long-distance land transport in NSW in the 1860s.

I had considered transcribing the entire series, or at least my edited version from The Herald in 1993, but discovered that the remarkable Jen Willetts has already done the job on her wonderful website. The only portion not transcribed by Jen is the following poem which concludes the series:

Tho’ far removed, my footsteps roam no more

The mazy windings of Newcastle’s shore

Tho’ now, no more, I rise at early dawn,

To tread the Flagstaff’s undulating lawn,

With buoyant step, each morning to inhale

Th’ inspiring freshness of the ocean’s gale;

Nor thro’ the town, alone observant stray,

Nor view with tireless wonder, day by day,

The Iron Horse rejoicing in his might,

Speed o’er the rails, with wild, resistless flight ;

Nor gaze upon that mystic length of wire,

Along which speed the messengers of fire;

Nor view within the Barracks panneled square

The volunteers, gay rob’d’ assemble there,

To learn those arts, by which the brave oppose

The dire aggressions, of ambitious foes;

Nor watch at eve, from off the neighbouring hill,

When earth , and air, and ocean all are still,

The wearied sun, slow sinking to his rest,

In golden glory cleave the ocean’s breast;

Nor mark beneath, the gathered shades of night,

The beacon flame, that gleams on Nobby’s height,

To guide the midnight wanderers o’er the deep,

To where the Hunter’s peaceful waters sleep;

Full oft, in waking dreams, at close of day,

On Fancy’s wings, borne onward, and away

O’er pathless wilds, and tangled forests green,

Where yet man’s wandering footsteps ne’er have been,

I’ll revisit the vale, and higher lands

Where fair Newcastle’s scattered city stands,

Once more, my former rambles I’ll resume

Amidst the windings of the tunnel’s gloom ;

Again I’ll roam along the restless shore,

Whose cavern’d cliffs resound the breakers’ roar,

And by the wharf, with pensive step repair

To watch the anchored vessels floating there,

Where D. A. R. appears with studious mien,

Replacing planks where’er a leak is seen,

Or figure-heads, which once like things of life

Had seemed, though now defaced by oceans’ strife,

Again with Walker, or my friend D. F.,

I’ll rove the hill, or climb the eastern cliff,

To view the main, where winds and waves contend,

And gliding barks, in lengthened lines extend,

Again I’ll meet those friends whom there I know,

Again rejoin the chosen, cheerful few;

Again live o’er those joys, a numerous train

That once were mine, but ne’er shall be again;

Yet though these pleasures all are left behind,

Naught shall erase thelr memory from my mind,

Their recollection oft will cheer my soul,

When griefs assail, or troubles round me roll,

And thoughts of joys, that once were mine to know,

Will shed a halo o’er the darkest woe.

Oh fancy dear, and memory ever blest,

Ye sweet companions of the human breast,

In absent hours, without your genial aid,

This life would be a wilderness of shade:

Joys sunken seen would leave no setting glow

To cheer our hours of after gloom below,

The varied past would be for ever gone,

And like the future all its joys unknown;

But through your power departed pleasures live

And hop’d-for joys, a certain comfort give,

And thus our hearts are soothed in every scene;

With memories of joys that once have been,

Or cheered with thoughts, as onward still we roam,

Of happy days, and pleasures yet to come.