The appearance in 2022 of a new screen version of All Quiet on the Western Front has brought many of my thoughts on this extraordinary book back to mind.

All Quiet on the Western Front was, strangely, a book that I deliberately skipped reading for a very long time. Even though I keenly hoovered up scores of books about The Great War of 1914-1918, I had a prejudice against Erich Maria Remarque’s book that wasn’t based on anything sensible.

I guess, for a start, I wasn’t so interested in looking at the war through the eyes of “the enemy”. Australia, as I have noted before, is a surprisingly militaristic country. An important part of its mythos stems from World War 1, in which Australia lost a remarkably high (in per capita terms) number of men – mostly on the Western Front. The loss of about 60,000 dead, from a population at the time of about five million, had a profound effect on the national psyche, the impact of which still reverberates a century later.

The other aspect of my decision to bypass All Quiet on the Western Front was its fame. In a kind of literary snobbery I assumed that if a book was really popular it must be bad. I call this “the Dan Brown effect”. One day, however, I was in a second-hand bookshop and my eyes lit on an older hard-cover copy of All Quiet, which I decided to buy and read. I devoured it quickly and realised how mistaken I had been for so long. This was a masterpiece, I immediately acknowledged.

Suddenly I was extremely interested in this book I had for so long neglected and ignored. Delving a little into the history of the book I learned something about its author, the impact the book had on him and his family and its political impact and ramifications.

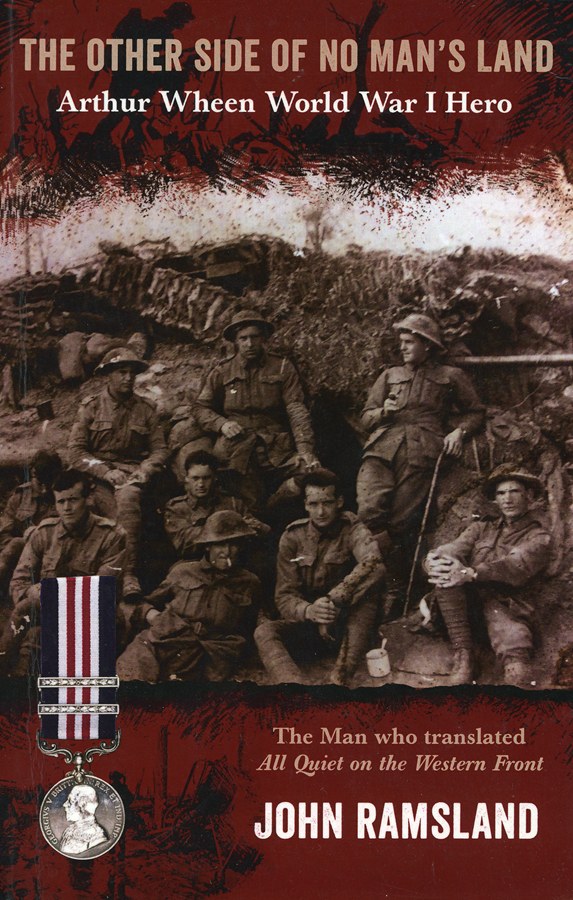

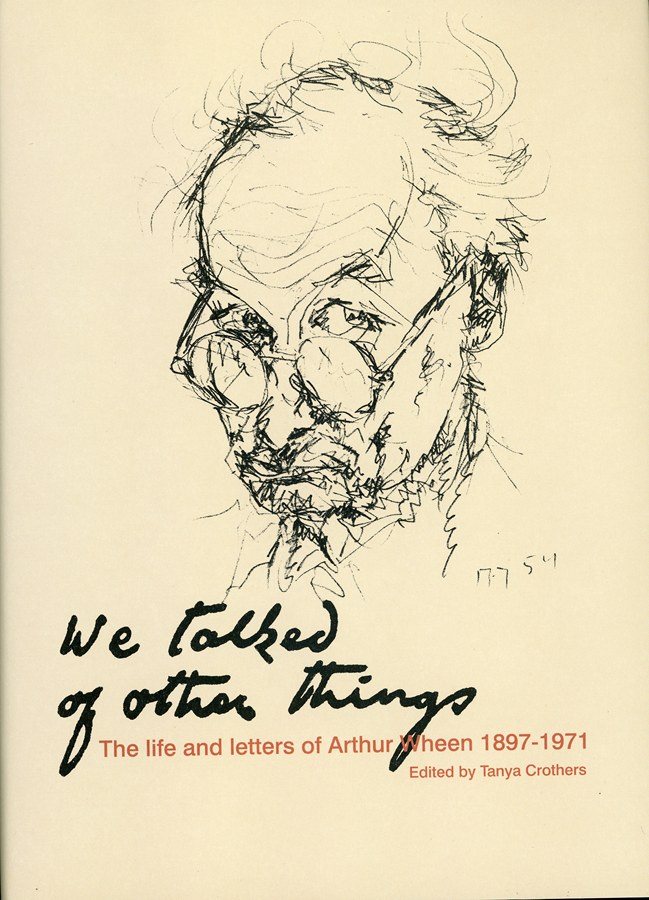

Next, having discovered that the man who translated the book into English was an Australian Great War soldier, Arthur Wheen, I also tried to learn what I could about him. I discovered, for example, that Remarque regarded Wheen’s translation as something of a standalone masterpiece in its own right – a new work of art, if you can accept that idea.

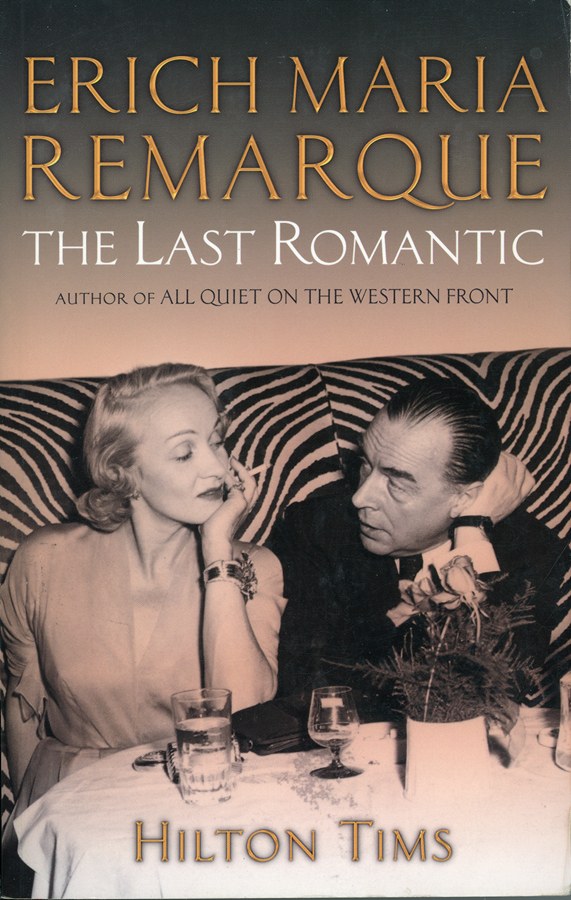

I located and read biographies of both Remarque and Wheen, and learned much from both. I believe that, one day, somebody should make a documentary film about the book and its place in history, tracing the lives of the author and translator to help modern readers understand why All Quiet on the Western Front was such an important and influential work.

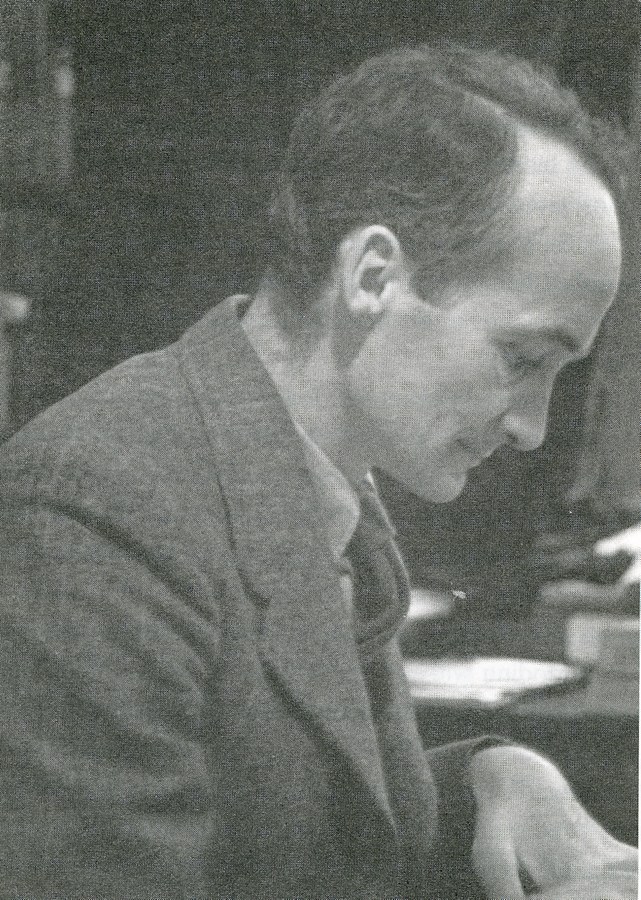

Remarque fought as a German infantryman in the war, but the book is a novel and not autobiographical. Naturally it draws on his direct experiences, but he could not have – and did not – experience many of the episodes described in his book. He was an unwilling draftee to the army in late 1916, entering the conflict long after the real horrors of it had become clear. He was wounded at Passchendaele in July 1917 and successfully strove to avoid being returned to the front.

Before the war Remarque had been a teacher (he quit) and had dabbled in writing poetry and earnest literary material with modest success. While recuperating from his wounds he began to write again and after the war he continued on this path, writing advertising copy and working in journalism – honing his storytelling skills. In 1927, unhappily married and with some unsuccessful literary efforts behind him, Remarque started writing a book about the war. He later claimed the idea had not occurred to him before, and he also said the novel was written quite quickly over the course of about five or six weeks.

Far from believing he might have written a best-seller, Remarque sat on his manuscript for six months. Some friends told him there would be no market for such grim work. There were already hundreds of war memoirs on the market, and many people thought there was no room for another. His wife and others, however, urged him to try to have it published. It took some effort to find a publisher, but once it was published it struck an immediate chord with readers.

On its first day of publication in book form in Germany – January 31, 1929 – the book sold out and demand for more copies surged. In the first few weeks the book sold at the rate of 20,000 a day by the end of 1929 it had sold almost a million copies.

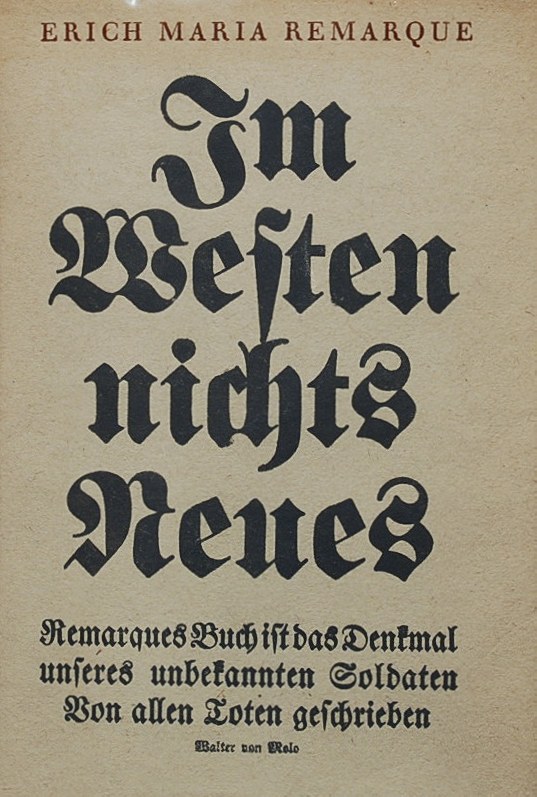

The name, which in English has become All Quiet on the Western Front, was in German Im Westen Nichts Neues – a play on a standard phrase used in official war communiques – “Nothing new on the Western Front”. The book instantly polarised opinion wherever it appeared. Most of those who had experienced the war as draftees, recruits and volunteers in the ranks recognised the truth and horror of it and praised it accordingly. Those who wanted to maintain the status of the military and the glory of participation in the armed forces hated it and wanted it suppressed. Interestingly, left-wing critics disliked it too, seeing it as a missed opportunity to campaign against the global economic status quo.

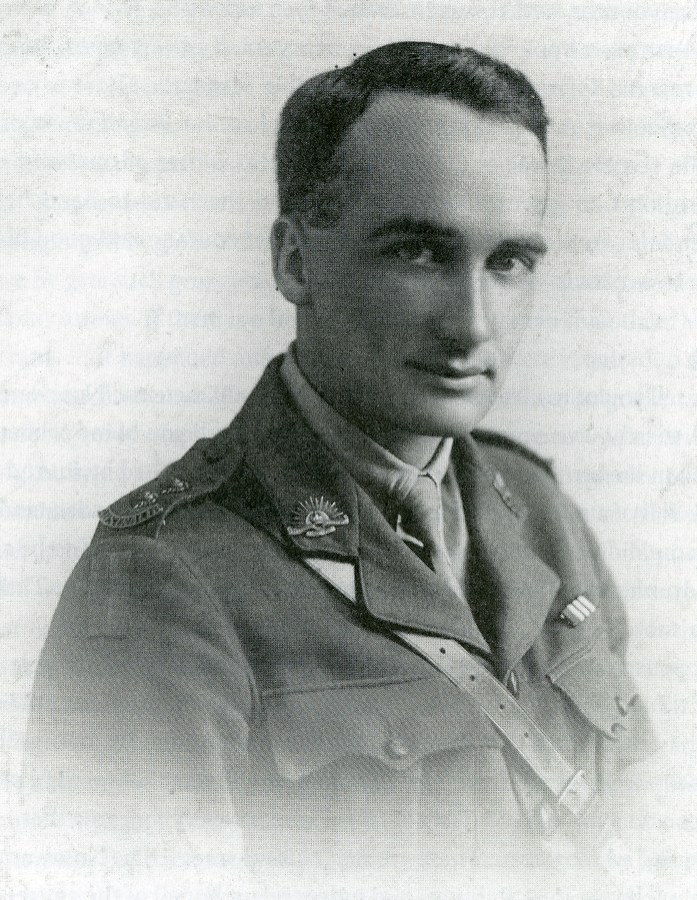

Arthur Wheen, soon to be chosen to translate Remarque’s book into English, had been a soldier too, though from a very different background. Born into a Methodist family near Bathurst, NSW, Australia, Wheen had a genteel and privileged background, was educated at the exclusive Sydney Boys’ High School and served in the cadets in the lead-up to the war. He volunteered in September 1915, became a signaller and was sent to Egypt in early 1916. He found his way to the Western front and won the Military Medal at the bloodbath of Fromelles in July 1916. He later received two bars to that award, and his long experience at the front was laced with many episodes of indescribable horror – hinted at in his letters home and in his own later literary efforts.

Wheen was badly wounded on September 6, 1918 and was lucky to survive. While recuperating he began to plan a hoped-for future as a scholar. He returned to Australia in 1919 and won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford. With a crippled left arm and plenty of mental and emotional scars, his academic success at Oxford was limited, but he met and mixed with many notable figures in the English literary scene. He wrote about the war – a novella entitled Two Masters – and in 1924 was working as assistant librarian in the Victoria and Albert Library in London.

Wheen’s literary contacts put him in line to translate Remarque’s sensational new novel, under pressure of time and also the expectation of it being a huge seller in the English-speaking markets. He succeeded admirably. The book sold in vast numbers despite the backdrop of the Great Depression and became one of the greatest publishing success stories ever. His war experiences had turned Wheen into an opponent of militarism and there is no doubt that his own thoughts and feelings helped him make the translation of Remarque’s book into the masterpiece it is acknowledged to be.

In answer to critics of the tremendous overnight wealth the book had brought to Remarque, Wheen wrote: “What it cost Remarque to qualify to write his superb stories he has told us in his books. However much money he may make by them he will continue to be out of pocket. You can take it from me that one hour under an artillery barrage at Ypres or the Somme would convince you . . .”

In a comment on Remarque’s praise of his translation Wheen wrote: “It is kind of Remarque to put such store by my translation of his books, and I am grateful to him for his confidence, though I am sure also he could easily find a better translator and should not feel at all aggrieved if he did so. It is great labour to me to translate, at any time, but I like working for Remarque and willingly do what I can to make his English as piercing as his German, however indifferently I may succeed”.

Wheen’s deliberately indirect style of translation – sometimes criticised by those who claim they’d prefer purely literal rendering – is readily seen in his poetic creation of the English title. “All Quiet on the Western Front” works better in English as a title because of the tone of its language, and because the reference to German official wartime bulletins would have been lost on English-speaking readers.

All Quiet on the Western Front made Remarque extremely wealthy, but it also turned him into a centre of unwelcome attention, especially among the upper echelons of the rising Nazi Party of Adolf Hitler. The Nazis were promoting renewed militarism and saw the book as counterproductive to their aims. They and their allies attacked Remarque, claiming he was Jewish and that he had never been near the front lines in battle. The Italian Fascist government banned the book and as the Nazis gained power and popularity in Germany they ratcheted up their rhetoric against pacifists and anybody whose work might be seen as undermining militarism and war.

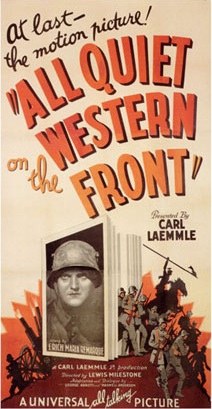

When the film version appeared in 1930 it too was a sensation. An early “talkie”, it was produced by America’s Universal Pictures with a record-breaking budget of $1.25 million.

The Nazis staged a major publicity stunt around the Berlin premiere season of the film. Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels had approached Remarque and tried to have him denounce the film as an unauthorised misuse by Jewish pacifist interests of his famous book. Remarque refused the chance to make friends with the Nazis, so Goebbels organised a large-scale demonstration by brownshirts who crashed the screenings and attacked filmgoers, following up with larger and larger demonstrations on the following nights until the German Government voted to ban the film on the basis that it was harming Germany’s image abroad.

The film was banned in many places, including for a time Australia and New Zealand – apparently for its grim “vulgarity”.

Remarque bought a house in Switzerland and transferred most of his assets there. When Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933 Remarque was in Germany. Friends warned him to leave immediately – which he did. His name was almost immediately published among a long list of high-profile Germans outlawed on the basis of alleged disloyalty. Book-burnings began to occur, and Remarque’s work figured among the target publications. In 1938 the Nazis accused him of insulting the memory of the dead soldiers of The Great War and stripped him of his German citizenship.

Remarque travelled to the United States where he stayed beyond the reach of the Nazis through the course of World War 2. The Nazis murdered his sister in his stead, in December 1943, accusing her of disloyalty to the Reich.

Despite all the accusations against him Remarque was scarcely a political person at all. His achievement and his crime was simply to have managed to capture the way the First World War really felt to millions of its victims.

After he became wealthy he lived the life of a playboy. He accumulated assets, built up a huge and valuable art collection, had relationships with numerous women including high-profile film actresses including Marlene Dietrich and Paulette Goddard (whom he married). He wrote a number of other books, which were generally well-received, but nothing else he wrote came near the success of All Quiet on the Western Front.

Remarque died in 1970. Largely forgotten around the world, he is today revered in Germany, especially in his former home town of Osnabruck, which awards a cash prize for pacifist literature in Remarque’s name.