Opinion by Greg Ray. October 11, 2023

About the middle of last week, before the Hamas attack on Israel, I had a dream about Palestinians. This is unusual since I am by no means deeply invested in the Israel/Palestine issue, though I have often thought about it.

In the dream I was in a park and a group of people I somehow knew were Palestinians (dreams are like that) were sitting at a picnic table and having a conversation. The people looked suspicious and unhappy.

I thought I should go and talk to them because I didn’t want them to imagine I was thinking badly of them. I wanted them to know I was interested in their problems. But when I tried to talk to them they were dismissive, though not hostile. They made it clear to me that anything I could say to them was more or less irrelevant: that their problems were not something I could either understand or help with. In their brief discussion among themselves about my approach to them they used the word “Nakba” repeatedly.

“You can never understand Nakba,” they told me, before dismissing me from their presence.

I woke from the dream with the word at the front of my mind. I wondered whether I had heard it before; whether it was a real word that I subconsciously remembered, or whether it was a made-up word that my dreaming mind had created. Before it drifted from my mind and was lost – as many dream elements often are – I went and looked up the word. It was a real word, as most people probably already know, and I read the Wikipedia entry on the topic with interest.

At the time I assumed the appearance of this word and this subject in one of my dreams was a subconscious reference to Australia’s Voice referendum, which is generating such sound and fury. My dreams do this, often. They reshuffle things I’ve seen or heard in waking life and put them together in unexpected ways, sometimes making me see things I hadn’t noticed before. I suppose my subconscious connected the ideas of Nakba and the Referendum because many aspects of the Wikipedia explanation of the Nakba – the sudden but ongoing dispossession of Palestinian Arabs by Jewish settlers that began in 1948 with the foundation of Israel – clearly shared much with the feelings of many Australian Indigenous people, whose reference to “Australia Day” (January 26) as “Invasion Day” so irritates and infuriates some non-Indigenous Australians.

I noted, on a second reading of the Wikipedia entry, that the word Nakba – which means “catastrophe” – originally dated to 1920 when Western colonial powers divided the Arab world into artificial nation-states that suited their own commercial and geopolitical interests.

Then came the Hamas attack, and Palestine was brought to the centre of my consciousness.

Nakba means “catastrophe”

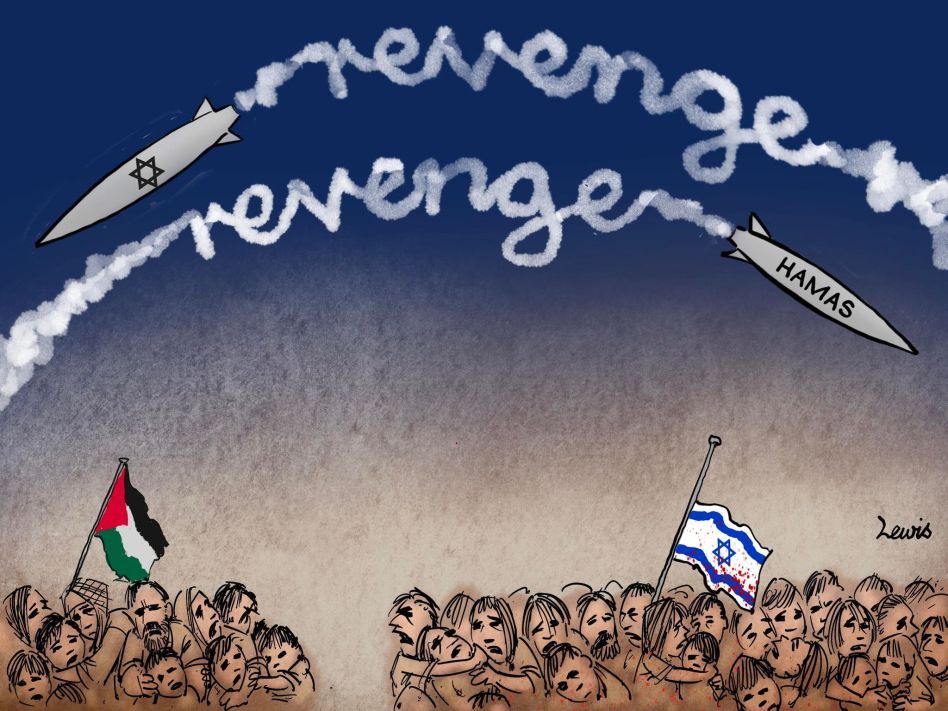

Before the recent Hamas attack I had formed a view that the Israel-Palestine issue would never be resolved while leaders on both sides seemed so determined – often for their own political reasons – to avoid any genuine attempts at reconciliation. After the attack and the retaliatory counter-strikes I can’t help feeling that the already remote prospect of resolution has become even more vanishingly unlikely. Politically, Israel had been going through a very rocky patch, with right-wing strongman Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu striking powerful community opposition to his plans to force through changes to the court system, designed to permit new laws to favour the religious extremists upon whom his grip on power depends. Netanyahu has also been fighting criminal charges and it seemed as if his long reign might soon end in acrimony.

It would appear that the Hamas attack has changed all that, bringing immediate solidarity to Israeli politics as the nation rallies behind Netanyahu and his massive revenge campaign. If there was any hope of Israel moving to a more moderate position in relation to the Palestinians who live in a state of siege in Gaza and in shrinking enclaves on the West Bank, it seems that hope has evaporated as a new cycle of bloodshed begins.

Hamas, the extreme hard-line Muslim organisation that runs Gaza, was helped into existence years ago by Israeli military intelligence as a counterweight against the non-religious Palestinian resistance movement. It has been acknowledged by many that this was a mistake, and if anybody doubted that they probably don’t anymore. By its recent actions Hamas has put itself beyond the pale for most observers and it is clear that ordinary Palestinians, once again, will pay, and pay, and pay.

The difficulty of moving extremists on either side towards genuine reconciliation is a matter of regrettable record.

Consider what happened to Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, murdered by right-wing Jewish activists in November 1995 because they hated his plan to make genuine peace with the Palestinians. This plan involved returning some confiscated lands, which infuriated those who had taken those lands and those who feared the Palestinians would take advantage of concessions to escalate violent attacks. It also deeply angered far-right religious extremists, especially when Rabin declared that he did not see the Jewish scriptures as “a historical land registry”. Rabin was a respected and successful former military leader with direct experience of Israel’s wars and of the forceful suppression of Palestinians. Perhaps because of what he had seen and been directly involved in, he was deeply committed to finding lasting peace as the best means to safeguard Israel’s future.

Benjamin Netanyahu’s role in Israeli politics at that time perhaps indicates how matters must continue to unfold in 2023. As leader of the right-wing Likud party, Netanyahu venomously opposed Rabin and his peace plan, aligning himself with extremist religious leaders and others, some of whom openly called for Rabin’s death.

Netanyahu v Rabin

According to Wikipedia: “In July 1995, Netanyahu led a mock funeral procession featuring a coffin and hangman’s noose at an anti-Rabin rally where protesters chanted, ‘Death to Rabin’ The chief of internal security, Carmi Gillon, then alerted Netanyahu of a plot on Rabin’s life and asked him to moderate the protests’ rhetoric, which Netanyahu declined to do. Netanyahu denied any intention to incite violence”.

Some religious extremists argued that Rabin had made himself subject to a death sentence under religious law by proposing concessions to Israel’s enemies. At a pro-peace rally attended by 100,000 supporters, Rabin reportedly said that “I always believed that most of the people want peace and are ready to take a risk for it”.

Rabin took the risk and after that rally he was murdered. The man who pulled the trigger was a 25-year-old law student with far right views whose threats and actions were allegedly not viewed seriously by Israel’s security apparatus. Wikipedia again: “The assassination has been described as emblematic of a kulturkampf (“cultural struggle”) between religious right-wing and secular left-wing forces within Israel. Ilan Peleg of the Middle East Institute has described Rabin’s assassination as “reflecting a deep cultural divide within Israel’s body politic […] intimately connected with the peace process” which illustrates both increased polarization and political conflict in the country”.

This deep schism is plainly evident in the recent debate over Israel’s court system. [It may be worth noting that the alliance between far-right politicians and religious extremists is not exclusive to Israel, as events in the United States and broader West often demonstrate.]

Because the murder of Rabin also killed the Oslo Peace Accords on which he had been working, political observers have described his killing as “the most successful” political assassination in modern history – in terms of achieving the goal of those who supported the murder.

Again according to Wikipedia, in Rabin’s pocket when he arrived at hospital after being shot was “a blood-stained sheet of paper with the lyrics to the well-known Israeli song “Shir LaShalom” (“Song for Peace”), which was sung at the rally and dwells on the impossibility of bringing a dead person back to life and, therefore, the need for peace”.

I hope it is not considered unseemly for me to wonder aloud how different things might be today for Israel, the Palestinians and the world, if Yitzhak Rabin had not been murdered by the extremists who were opposed to peace. It seems the extremists on both sides of this conflict are locked in an embrace of mutual dependence fuelled by relentless cruelty. I can’t see how the bloodshed can stop until their influence is diminished.

Indeed the bloodshed may well expand beyond the borders of Israel/Palestine, with the US moving a powerful aircraft carrier strike group “to support Israel”. This would seem unnecessary if only Hamas were in the cross-hairs but it might make sense when one considers the almost immediate Western media speculation that Iran might have supported the Hamas attacks. As a hated enemy, a Muslim theocracy and a member of the BRICS alliance attempting to break the global US dollar hegemony, Iran has for years been a target for furious rhetoric, heavy economic sanctions and other hostile measures from both Israel and the US. I would not be amazed if this violence grew into a larger regional confrontation.