When the story of the Titanic submersible disaster broke, my mind instantly went back 20 years to an interview with the first and – up until then at least – only Australian to have visited the wreck of the sunken liner. I had always remembered that interview because of the strange way Andrew Rogers wound up on the trip and because of the story he told about the submersible almost becoming trapped on part of the wreckage.

Andrew’s Titanic tale began in 1997 when he and his wife Winnie were planning a trip to India. They were shopping in an Australian supermarket for some packaged cheese to take away with them when Winnie – a devoted competition junkie – filled in some coupons with a Titanic dive as first prize. They were in Mumbai when they got word that their entry had been picked from about 270,000 and from that instant Andrew was intent on going on the dive – the first commercial tourist dive to the famous wreck.

Andrew told me that the trip had been organised by an Australian named Mike McDowell who was living in Germany at the time and who specialised in arranging unusual adventure holidays. ”Mike McDowell had booked up a couple of Russian vessels to do the 11-day trip in September 1998. There were 16 people doing the dive: fare-paying passengers and prizewinners like me. If you had to pay the trip cost $65,000 a person,” Andrew said.

The trip nearly didn’t go ahead: there was court action by a Florida-based group that held salvage rights over the wreck to prevent it occurring. Andrew said he and his fellow tourists were named in court papers of being in contempt of US laws. “Even when the dives were finished the American passengers were not allowed to talk publicly about them. That didn’t apply to me, of course.”

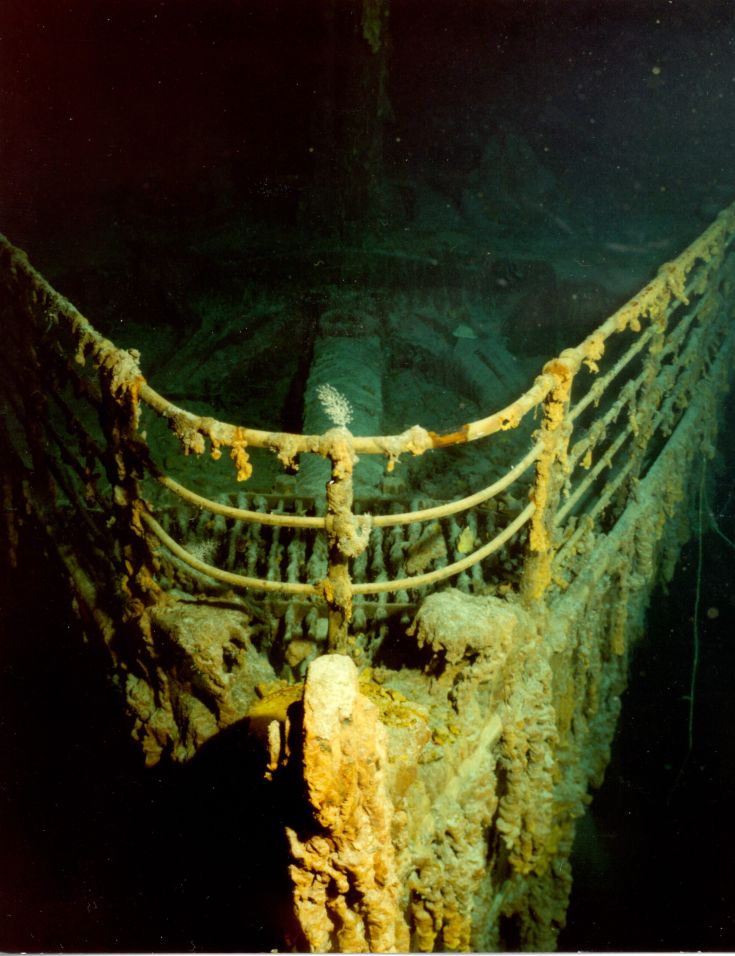

In the two-and-a-half hours it took for the pair of Mir submersibles to steadily drop 4km to the bottom of the sea, Andrew had to keep reminding himself he was still on the same planet. At 150 metres the little submersible was completely enveloped in blackness, though it was just 11am in the rough North Atlantic. “The water was clear enough, but the only light was what came from the submersible,”‘ Andrew recalled. On his way to Davy Jones’ locker he and his two companions – the sub pilot Genya Chernaev and the other passenger Roman Sugden – saw a handful of fish, one crab and some prawns. But his biggest impression was the vast amount of water in the sea and a great sense of nothingness. Until the wreck loomed in sight. “To travel so far straight down through all that black emptiness and then to see something made by human hands: it was a bizarre feeling,” he said.

With Andrew in the tiny Mir capsule was an American undertaker. “His boss was really rich and had shouted a couple of his staff these trips as a sort of loyalty reward.” So, dropping like a slow-motion stone into the freezing Atlantic, sitting beside a Russian pilot and an American undertaker, Andrew was contemplating the careful exploration plan the group had mapped out while still aboard the mother ship. But when the great bulk of the ship, sitting broken but majestic on the ocean-floor, loomed out of the darkness, the plans were thrown aside. “As soon as we saw it we just got excited,” he said. “We kept telling the pilot: ‘Go here, now go there. Let’s look at that’. You’d keep seeing different things and getting carried away wanting to look at everything.” The trio had just five-and-a-half hours to spend exploring both halves of the massive wreck. But Andrew said it was nowhere near long enough to see everything. “Apart from the wreck itself there is all sorts of stuff just lying on the seabed. Shoes, boots, toilets, cups and plates.” Owing to the sensitivity of the owner of the salvage rights, Andrew and his companions brought nothing away from the scene – except a small rock.

The most memorable part of the dive came when the sub reached the massive overhanging stern of the wreck.

“We knew the pilot of the other submersible just wouldn’t go under there under any circumstances. It was considered dangerous. But we really wanted to see the propellers up dose and we begged and pleaded with our guy until he agreed . We manouevred in underneath and had a good look. Then, when it was time to get out, one of the skids of the sub got hooked on something and we couldn’t move out. Our pilot was a very calm guy but I was looking at him as he shuffled the sub back and forward trying to unhook it. He was definitely looking very grim. For a while we really regretted talking him into going under there, but he finally wiggled free.”

After the trip Andrew became something of a Titanic fanatic, giving talks to various groups in his home town area. I certainly never forgot his graphic description of almost being trapped in the blackness of the great ship’s tomb.

Andrew’s story came even more clearly to mind when I read this account of another Titanic dive that almost ended in disaster, in much the same way that Andrew’s trip almost came unstuck.

Following the recent Titan submersible disaster, Andrew remarked that a major contributor to the failure was the shape of the habitat chamber. “Every single deep diving submersible constructed in the history of this kind of activity, has had a spherical habitat chamber, basically, a ball. None of those have ever failed,” he said.

“The cylindrical shape of the Titan’s chamber was as much a contributing factor as the material of its construction.

When you have 6000psi of pressure bearing down with equal intensity on every square millimetre of the habitat chamber, you can’t afford to have any weak points. A cylindrical chamber has a massive weak spot – the full curvilinear circumference … to put it in simple terms – the entire red area of a Coca Cola can! Stockton Rush had a degree in aeronautics and used a formula of relative strength to weight to decide on the use of carbon fibre in his habitat chamber construction. That would make sense in aeronautics but is totally impractical for deep ocean exploration. It was untested and totally unable to withstand the fatigue caused by massive pressure and temperature fluctuations.”