During the 1970s the Newcastle firm of Carrington Slipways was seen as part of the strong backbone of NSW industry. Over some decades the firm, founded and owned by the Laverick family, had invested in excellent ship-building and repair facilities and had developed a strong skills base. Carrington Slipways launched about 120 ships of various types before the government wound back protection for the Australian ship-building and repair industry. In its last years, culminating with its closure in 1990, Carrington Slipways campaigned to be part of Australia’s big submarine and frigate contracts. These contracts were subject to intense political and commercial lobbying and Carrington Slipways’ bid failed. Its closure followed almost immediately.

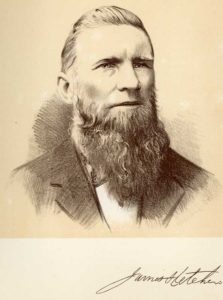

The story of Carrington Slipways begins with its founder, the remarkable John Fisher (Jack) Laverick, who was born in Newcastle-on-Tyne, England, on June 6, 1899. He trained as a shipwright and served as an aircraft rigger in the Royal Flying Corps in World War 1. He was injured on duty and suffered a severely damaged hip, an injury that was to plague him all his life. Injury notwithstanding, Jack went to sea in 1920, serving as a carpenter on various ships, travelling to Australia where he turned to his hand to a variety of jobs including a stint with John Brown at Hexham (near Newcastle, NSW) and at Newcastle’s Walsh Island dockyard. He was back at sea soon enough, with an eventful sailing voyage on the steel ship Bellpool to England via the nitrate port of Tocapilla, Chile, and on the steamer Belgot to Calcutta. Injuring his hip again, he decided to migrate to Australia where, after a period of recuperation, he threw himself into any work he could find, ranging from door-to-door sales to real estate work. He married in 1929 and built a good business selling car tyres until the Depression hit and, with two young sons – Peter and Donald – to support, he tried farming in the Burragorang Valley.

Next Jack broke his hip again, his wife Molly had a serious nervous breakdown, they lost the farm to the bank and wound up in Gladesville where Jack was obliged to take a job as a debt-collector and where a daughter, Elizabeth, was born. A friend talked him into travelling to Port Moresby in 1937 for a supposedly well-paid job which turned out to be a mirage. Incredibly, Jack decided to join another man, Don Marshall, in a bid to get back to Australia in a dug-out canoe. Jack made a written record of this gruelling and dangerous trip, finally making landfall at the Lockhart River Mission in North Queensland where the two men were nursed back to health.

With the Depression past its worst, Jack got a job as a travelling salesman for a ships’ chandler firm and the Lavericks moved to Lane Cove. By 1942 Jack was back working as a shipwright on war-related jobs around Sydney Harbour. This work ran out in 1946 after the war ended and Jack turned his hand to whatever jobs turned up. In 1948 he won a contract to build two 6m flood boats for Richmond-Windsor Council. He and his son Don built these in their backyard.

In 1949 the Lavericks moved to Marks Point, Lake Macquarie, hoping to start a business hiring boats there. After a few false starts at different jobs, Don became formally apprenticed to his father Jack as a trainee shipwright. Unfortunately, the boat hire business was unsuccessful, so the father and son team took on all kinds of building and engineering work as well as boat-building and ship repair. In the early 1950s Jack also took a handful of voyages on coastal and Pacific Island trading ships. Don spent his last year of apprenticeship working at Newcastle State Dockyard, to get some experience on bigger vessels, and he spent three months at sea on the Fiona in 1953 to get his required “sea-time”. Another of Jack’s sons, John Jnr, started a shipwright apprenticeship with Jack in 1953.

Recalling his year at the State Dockyard, Don Laverick said it was “like a nursing home”. On his first day there, he said, the foreman shipwright asked him at 7.30am to lift and prop a launch, ready for repair. “When I told him at 9am that the job was finished he told me it was supposed to have taken all day.” Don said the yard did good work, but was very slow compared to a private business.

In the midst of this, Don also did his National Service in the Australian Army, based at Ingleburn. “I was a sergeant when I left. They wanted me to stay on and do officer training, but I wanted to get back to work,” he said.

In June 1957 Jack and his two shipwright sons were repairing a tug in Newcastle Harbour when they were approached by a shipping providore, Bert Lovett, who proposed a 50:50 partnership in a boat slipping and repair business. Bert had an option to lease ideally sited land in Cowper Street, Carrington, near the bridge over Throsby Creek. Carrington Slipways started operations in August 1957. Already on the site was a shed, a slipway and a hand-winch (quickly replaced with a motorised version). The firm’s first big job was to build a wooden vehicular ferry for used on the Macleay River at Smithtown, but after that job most projects were built in steel. The Lavericks bought out Bert Lovett in August 1959.

By 1964 Carrington Slipways employed about 30 men. Don’s wife Maureen worked full-time running the office. Jobs included steel barges, tugs, pearling luggers and other specialized vessels and the firm was winning a high reputation for quality and reliability. In 1968 the number of employees was close to 100 and by this time Jack was almost fully retired, leaving most of the running of the business to Don and John Jnr.

Carrington Slipways was outgrowing its cramped site on Throsby Creek and in 1971 the firm began to move to a 16ha site near the Hexham Bridge at Tomago. In November of that year the oil search vessel Eugene McDermott was launched, then the firm began moving its gantry cranes to Tomago by barge. By May 1972 the shift was completed and two tugs had already been built at the new site. The official opening was on May 13, 1972, and coincided with the launch of tug number 71, the Roebourne.

Jack Laverick died on April 6, 1978, following his first wife, Molly, who had passed away on March 22, 1966.

According to Don, it was the Fraser Coalition Government’s decision to remove protection for Australian ship-building and repair that led to Carrington’s downfall. After World War 2 the Chifley Labor Government had decided that the industry was too strategically important to lose and that it should be shielded against competition from bigger, cheaper overseas firms. When this policy was abandoned the writing was immediately on the wall. Private clients flocked overseas for cheaper prices, making naval work vital for survival. Naval work, however, is intensely political, with influential politicians all pushing to have work done in their state or electorate. That put Newcastle at a huge disadvantage, since its political clout is negligible on the national scene. Carrington did win some work, notably two Rushcutter class minehunters and – back in 1979 – the refit of HMAS Tobruk.

Despite intense lobbying for the big prize contracts associated with the Swedish-led submarine build and the German-led frigate program Don believes the Newcastle company never had a chance. “I was told by quite senior people in the navy that we never had the slightest chance and that politics and money were against us all the way,” he said. The Lavericks hadn’t wanted to tender since it was a huge expense, but the government talked them into it on the basis that qualifying to tender would help them win other jobs. It didn’t. The government chose to buy second-hand equipment instead, leaving Carrington high and dry. Union campaigns for a 35-hour-week didn’t help either.

The Aurora Australis government icebreaker project also cost Carrington dearly. The government insisted on the involvement of the Finnish Wartsila Marine, which went bankrupt almost immediately after Carrington transferred it a very large sum. That was 1989. The Aurora Australis – the heaviest ship Carrington ever built – was launched in September that year. By the next year Carrington was itself finished. The Lavericks maintained that, if they had not transferred that sum to Wartsila they might have survived. Instead, immediately after the announcement of the navy’s frigate contract, the Commonwealth Bank sent its officers to demand repayment of $750,000 – a big amount in those days.

“They demanded the keys to the place and to my company car,” Don recalled. “Then I had to go and tell the staff we were finished. It was the hardest thing I ever had to do at Carrington Slipways. The bank took everything I owned.” The bank called Don and offered to pay him to help them sell the company’s assets, but he was denied access to any of Carrington’s records and archives – including thousands of photographs of ship repair and launches over the decades – and these appear to have been lost forever.

Carrington Slipways’ last ship, the Searoad Tamar, was launched while the yard was in the hands of receivers. The yard was sold in 1992 to the Australian Submarine Corporation and has since passed through other hands, becoming a general engineering facility.

Back in 1990, in the process of trying to sell Carrington’s assets, Don found himself offered a job in Suva, Fiji. Captain Cook Cruises, in partnership with Qantas, had been lured to build a cruise vessel in Fiji but things had not been progressing well. Don and his wife Maureen flew off to Suva to help sort things out and ended up staying five years. The job was harder than expected. “They had big enough fuel tanks for a round-the-world trip when the ship was meant for local cruises. Then they only had enough water storage for a day’s needs, which is useless for the tourist business,” he said.

After the Fiji job Don was offered a management role at Sydney’s Garden Island. “The Keating Government was trying to get the dockyard ready to sell,” Don said. He spent a year there before being offered a big redundancy payment – an offer he cheerfully accepted. Typically very busy in “retirement”, he and Maureen continued with an almost bewildering variety of projects and pastimes. Maureen, for example, was a champion go-kart driver and Don, having already learnt to fly, went to TAFE to get a builders’ licence so he could build a set of home units at Morisset. Maureen died in 2021.

An interesting 2005 interview with Don and Maureen Laverick can be heard here, on the University of Newcastle’s Living Histories website.

An excellent video about Carrington Slipways can be seen here.

A good article about the Lavericks and the Aurora Australis, by Newcastle Herald journalist Ian Kirkwood, can be found here.

The cruise ship “Lady Hawkesbury” and the cement carrier “Goliath” were also built at Tomago.

They used computers in the early 1980s to “nest” plates and program the cutting of them to minimise waste.

I recall that the Aurora Australis was built from steel supplied from Finland.