Some years ago my late dear friend Dulcie Hartley shared these memories of the Great Depression with me. Dulcie was an amateur historian with wide-ranging interests. She wrote a number of very good books. Her Depression recollections are so interesting I’d like to share them more widely. Thanks to Dulcie’s daughter Venessa for her help.

My birth in January 1929 heralded the onset of a most disastrous year for the Goddard family. An unplanned addition, I joined my eight year old sister Vera and completed the family group.

During the same year my father, Sidney Goddard, became seriously ill and diabetes mellitus was diagnosed. Insulin treatment for this complaint was relatively new in Australia, and it was only after a lengthy hospitalisation that my father’s condition improved sufficiently for him to be discharged. During the next few years the medical profession referred to him as “a walking miracle.” Work had been fairly scarce the previous year and my mother, with a new baby and a sick husband, saw her savings gradually whittled away. As well, she had no family support as she and Dad had moved south from Queensland seven years previously.

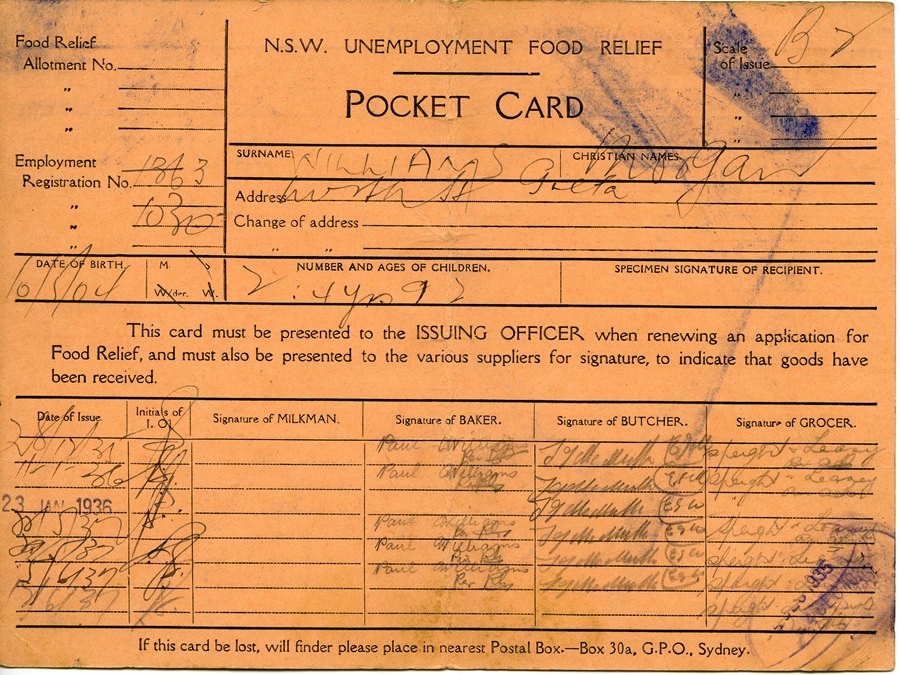

My father came from Tooting, south of London, where his father was the local policeman. In 1909 my grandfather, Henry Goddard, retired from the police force and migrated to Cairns in northern Queensland, where his daughter and her husband were living. Two years later my father left England to join his family in Cairns. He was a bricklayer, but as wooden homes were the norm in northern Queensland, he found other work and enjoyed the salubrious climate and the wonders of the Barrier Reef. In 1914, when Australia joined “the mother country” in the Great War against Germany, my father enlisted in Queensland’s Ninth Battalion and was soon on his way to Egypt. April of 1915 saw him landing on Gallipoli, where he survived several gunshot wounds and was in the final evacuation.

Dad transferred to 11th Field Artillery Brigade and was soon promoted to sergeant. He saw service in the trenches of France where he was seriously wounded in 1917 and hospitalised in England suffering from the effects of mustard gas and shrapnel wounds. Due to a bureaucratic bungle, his next of kin were advised that he had been killed in action. The family held a memorial service and black and gold memorial notices were printed. (My father kept one of these as a souvenir.) He was patched up and sent back to the front until the Armistice, eventually arriving back in Australia, “a land fit for heroes,” in January 1919.

Dulcie’s mother, Evelyn Clarice Goddard, nee Hyams

Dulcie’s father, Sidney John Goddard

My mother and father met in Cairns after the War. She had been born on the Queensland goldfields at Ravenswood, where her Jewish father was a gold buyer. However, by the time my mother was 20 both her parents had passed away. She was working her way around Queensland when she met and married my father at Cairns in 1920. Work was scarce so the newlyweds travelled south by ship to Sydney in NSW. My sister was born in Sydney and soon after Dad, hearing of the rapid industrial expansion in Newcastle, came north to investigate. Finding work prospects favourable, he purchased a small weatherboard cottage in Chin Chen Street, Islington, a somewhat run-down, working class suburb.

For a few years they prospered and my father purchased a second-hand car. (There weren’t too many in our suburb at that time!) However, the building trade, always the first to be affected in a depressed economy, slumped badly and by 1928 jobs were few and far between. And yet much worse was to occur the following October when the collapse of the New York Stock Market sent its shock waves reverberating worldwide.

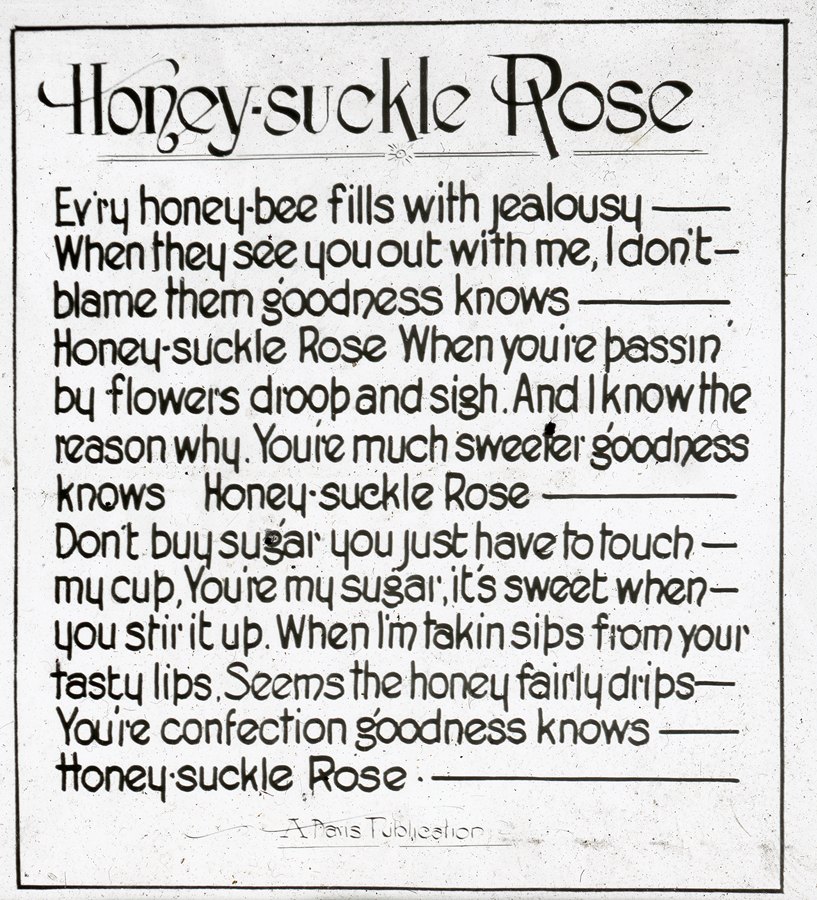

The socio-economic upheaval which followed saw my father still sick and our family savings depleted. My parents had no alternative than to apply for government assistance in the form of food relief, commonly known as “the dole.” Fortunately they owned their house, unlike the many people who lost their homes because they could not keep up the repayments. However, it was not easy to get the dole:

To obtain food relief, applicant must be registered at the State Labour Exchange for at least seven days, and he must make a declaration that he has been unemployed for at least fourteen days and is without resources which he might use for his support. If he possesses any property (with the exception of a house) which he might realise, he cannot obtain relief until all his resources are exhausted. If he is unable to realise his property, and is otherwise eligible, he may be granted relief on giving an undertaking that the amount will be refunded when circumstances permit. No discrimination is made in the case of destitute foreigners. People from other Australian states; however, may only receive food relief sufficient to enable them to return to their State of origin.

Assistance was given in the form of food dockets which had to be used at nominated stores. At first these were collected from suburban police stations, and hundreds joined “the dole queue,” waiting their turn exposed to the elements and often very hungry. Later members of the public service distributed these dockets from public halls and they were usually more civil than the policemen. A single man received five shillings and six pence per week for food relief and a married couple with two children received sixteen shillings and six pence. Even though food and clothing prices were only a fraction of those of today (1989), this amount was insufficient to provide adequate nourishing food. Owing to his poor health, dad was allocated one pint of milk per day, but most of this was given to me.

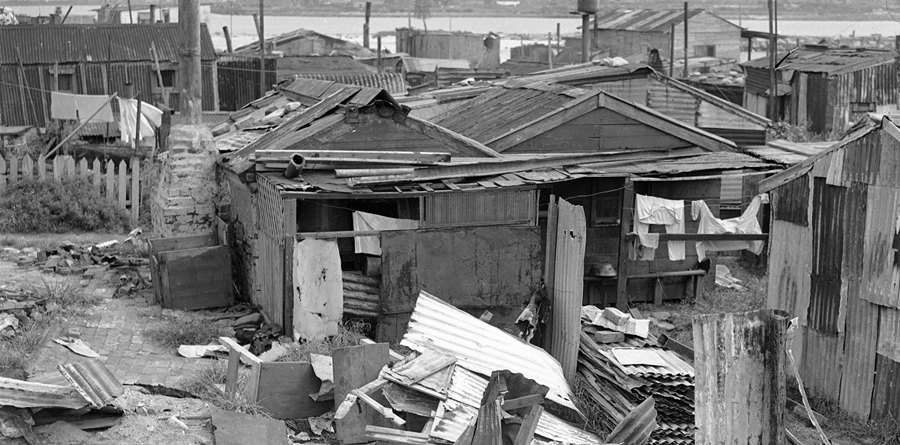

When my father was stronger he sought to alleviate our desperate situation. There were several “dole villages” scattered around the suburbs of Newcastle where destitute people had knocked together some form of shelter. Mostly they were people who had been evicted from their homes, or just left because they could not pay the rent. To subsidise their food relief, these residents were often dependent on hand-outs from soup kitchens run by various church organisations but these dole villages were often crowded and unsanitary, as well as being m full public view. Probably the largest of these settlements was at Nobbys in Newcastle and the following letter, written by the late Lottie Jenkins of Jayes Travel Service, provides an interesting social commentary.

Nobbys Camp was not as depressing as it sounded. The little humpies, shacks and tents were very well kept and the inhabitants seemed to try to outdo each other in creating little gardens around each one. It appeared a lovely spot to live in, with a beautiful beach, close to fishing, surfing, boating and the city. When we had visitors a walk to Nobbys was one of the tourist attractions.

This was a romanticised and elitist perspective of the dole village.

My parents did not want to be on public exhibition in their reduced circumstances and my father heard of a small group of people living at Fingal Bay, near Port Stephens just north of Newcastle. He was impressed with the area so, with a little help, built a bag humpy and we moved, taking our few possessions on a delivery truck. The house in Islington was securely boarded up because desperate people use desperate measures and it was not uncommon to find squatters moving into an empty home. Many residents were reduced to using the palings from the dividing fences for firewood as they had no money for gas or electricity. Even old furniture and lining boards were also used. Those who lived adjacent to railway lines were more fortunate as children were sent to gather coal which had fallen from the coal wagons.

The walls of our bag humpy were made from rolls of hessian and waterproofed with a cement wash. A bush timber frame had been used, the roof was of second-hand corrugated iron, and push-out wooden shutters provided light and ventilation. Our bunks were corn bags stretched over four posts driven into the soil. The uprights of a home-made wooden table and forms were similarly anchored to the ground. Mattresses were often stuffed with bracken fern which, although a bit noisy, did not seem to keep anyone awake. We had a few bags scattered over the floor. Wooden butter boxes and packing cases were used for cupboards. A safe, that is a ventilated cupboard for perishable foodstuffs, was made from a wooden frame covered with fly screen wire which was hung in a shady place under a tree. My father was handy and built a useful cooking arrangement. He cut the top off a ten gallon drum, hinged the top so that it would open and close like an oven door, and bedded it on its side in the open fireplace. The white clay in which it was set hardened from the heat, and I can remember many delicious blackberry pies which he made in this oven. Kerosene lamps and candles were used for lighting and a hurricane lamp was always carried when out of doors at night time. (At this time our home in Islington did not have electricity connected so we were quite accustomed to lamps and candles.)

Life at False Bay

Fingal Bay was then known as False Bay and we always affectionately called it “Falsie.” The dole village was roughly divided into two small settlements, one in “the Corner” where we lived and the other at “Middle Camp.” The humpies were usually made of a mixture of corrugated iron, canvas, hessian and driftwood and there were probably about forty altogether. Although made of such flimsy materials, there was adequate spatial territory between the dwellings. I suspect there was a floating population. I can remember there were people my family knew well by the name of Ward, Skewes, Presbury and Shepherd. I understand that others living there at this time were Jack and Ron Barry, Ron Sault, Fred Burt, Hiram Price and Bob Alexander. Middle Camp was on the site of the present surf club house and this was where the Prescott family lived. Later on other families came there including Roberts, Southwoods and Millwards.

Our move to False Bay was a wise decision and, as our diet improved, so did our health. Some men started small market gardens and the bountiful sea provided us with a healthy, if monotonous diet. I can remember my father patching up an old rowing boat and one of the professional fishermen from Nelson Bay must have given us a cast-off net. The men used to row out in the bay and put the net in. What marvellous hauls of mullet they pulled in. Dad built a smoke house and, using saw dust or whatever was available, dried and smoked the excess mullet. At certain times these fish contained roe and these were rich and nourishing. Sometimes a few of the men from the village helped the professional fishermen. A few fish and the occasional lobster was often their reward.

Our water supply came from a nearby spring and this was carried to our humpy in empty kerosene tins which had been fitted with a handle. The humble kerosene tin was a much prized possession in those years. By cutting down one corner and diagonally across the top and bottom and opening it up, a washing up sink with attached draining board was formed. The edges were rolled to prevent injury and to make handling easier. Toilet arrangements were rudimentary with a pit covered by a wooden box with a centre hole, and four posts surrounded by a hessian screen. My mother boiled the washing out of doors in a drum over the fire and bath water was heated the same way. We bathed in a miner’s tub which was a circular galvanised iron tub about one metre in diameter with two handles. Driftwood and packing cases were eagerly sought and my father made chairs and stools from these.

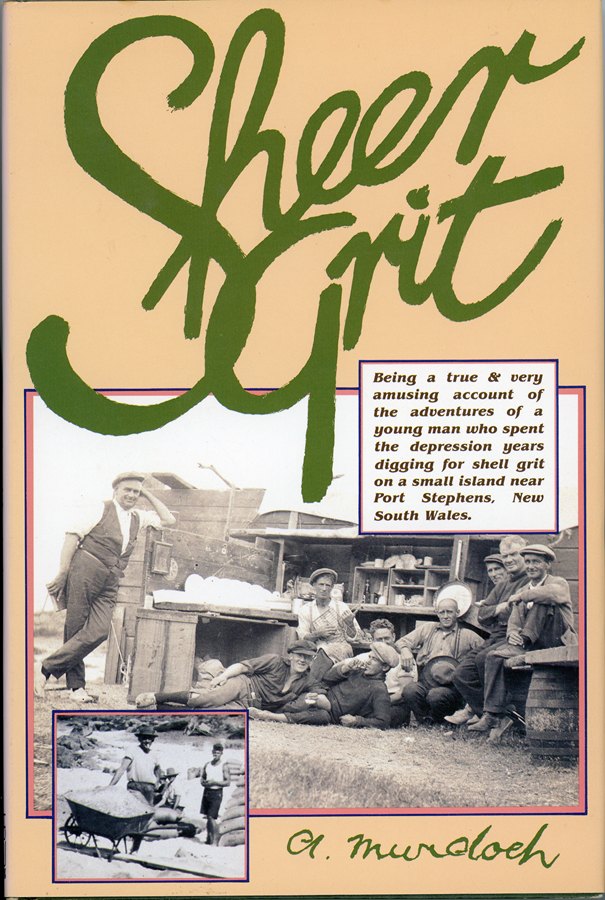

Each dole day the men would walk the four miles along the bush track to Nelson Bay, carrying a sugar bag which was more than adequate for the family’s weekly ration. There were two good stores at The Bay: Blanch’s and Cody’s, and the latter “sold everything!” They both stocked fresh bread which was about five pence a loaf, and according to Arthur Murdoch (author of the book Sheer Grit), competition was extremely keen between these stores at one time.

My sister Vera used this same bush track when walking to Nelson Bay School. She was often alone as school attendance was irregular from the dole village and she hated the long walk as she often saw snakes. Sometimes she was caught in the rain but such luxuries as umbrellas and rain coats were unknown to us during those years and Vera has very bitter memories of this period of her life. Both of us were brought up to be self-reliant and stoical (“hardy” was the colloquialism of the era used to described us). I did not consult a doctor until I was 14 and my first visit to the dentist had been one year earlier. If one of us complained mum would say, “Look at your poor father – he’s dying!” and that soon quietened us. Fortunately the rest, fresh air, improved diet and abstinence from beer and tobacco had a beneficial effect on my father’s health.

At low tide Vera and I often walked across the sand spit to the lighthouse on the island. This was the Outer Light at Point Stephens. We usually went to collect lemons which grew wild there and sometimes called in to see the lighthouse keeper and his wife. It was important to watch the tide as the sand spit was covered at high tide and very treacherous. I remember once being caught by the incoming tide and spending many hours at the residence, waiting until it was safe to return. Arthur Murdoch had a shack on the island and was eking out a living digging shell grit which was taken in the Coweambah to Newcastle where it was sold to poultry farmers. If fowls are not given shell grit the eggs shells become soft and crack easily. The island abounded in this product and, although the work was hard, Arthur preferred it to being on the dole. He used to come over to the dole village for a yarn and was well-liked.

Bushfires were a danger during the summer months and Arthur Murdoch wrote of one which caused great damage in the dole village. However, I have a lasting memory of an earlier one when the whole headland was on fire and the blaze continued until evening. Snakes were also a constant worry during the warmer months. Once I was sitting on a stool and on getting up and moving the stool, I found a black snake coiled up underneath. Another time my father carried home a hollow log for firewood (everyone was encouraged to bring some wood when they returned to the humpy) and when he threw it down out slithered a black snake. However, these were minor problems and we youngsters made our own fun with the lovely beach and clear blue waters of Fingal Bay our playground.

Smelly canvas sandshoes

Due to our straitened circumstances, sugar bags were highly prized in those days. My mother unpicked the stitching, boiled the bags in the drum or copper several times to soften them and then hemmed the edges. A piece of tape was sewn on the corner and the finished product hung from a nail on the wall, a rough hand towel for the whole family. After the same initial treatment of unpicking and boiling, my mother made others into aprons, trimming the edges with bias binding. Our clothing requirements while there were practically nil as we wore any old things. Our bed linen and clothing was patched so frequently that mum wound up patching the patches. Nearly everyone wore canvas sandshoes because they were the cheapest footwear available and bare, sweaty none too clean feet in these certainly produced a distinctive odour. Our sandshoes were so bad that they had to be left outside the door.

However, we kept some neat, tidy clothing for the occasional trip back to Islington to see that the house was in good order. We would walk into Nelson Bay, (I would have to walk to a certain tree stump before I was given a piggyback) and board the Coweambah. This little steamer, known to us as “the old Cowie,” made regular runs between Tea Gardens and Newcastle. I think we folk from the dole village were given a free passage. Mum was a very poor sailor and I remember her being very seasick and, although I was only about four, I had to get sweat cloths from the seamen so that she could tidy herself up. I suspect that we made monthly visits to Newcastle Hospital to get Dad’s supply of insulin. I remember many of these visits later on because it usually took a whole day of waiting in the outpatient’s department of Newcastle Hospital.

There was a good community spirit in the dole village, with the men working as a team when the fish were on and at other times playing crib, chess, draughts and cards for hours. The women seemed to be friendly and I know my parents forged some enduring friendships during those years. Arthur Murdoch, commenting on the residents of the dole village, said:

I occasionally walked round to see them and never saw a happier crowd of people. Everyone on the same level, no money but no worries. As times got a little better, one by one their former jobs were offered to them again. In conversations with them, as they returned to their old jobs and to resume their life in the city, they left with regret.

We stayed at Fingal Bay, with intermittent trips back to Islington, until I was due to commence school in 1934, when we came back permanently. My father was offered an invalid pension of one pound per week, but he rejected this as being totally inadequate. He obtained work “on relief” – that is a few week’s work on the basic wage of three pounds nineteen shillings – and his first job was as “billy boy” for a pick and shovel gang working in Islington Park. These gangs were employed on suburban works such as road making, kerbing and guttering and park maintenance. The men were supplied with picks, shovels, wheelbarrows and one concrete mixer for each gang. Planned as labour-intensive work, this was one way of sharing the jobs. Municipal councils were allocated government funding for road works and men were employed on a week to week basis, while work and funds lasted. Great was the derision of the neighbours when my bricklayer father became a billy boy, but the same people had little compunction in trying to borrow a shilling to make a bet on a racehorse once they knew money was coming into the household.

There was certainly a difference in the Islington community, as compared with the dole village at Fingal Bay where we had all shared and helped each other. Morale in Islington, like other densely settled inner suburbs of Newcastle, was extremely low. Many people had been “put out on the street” with all their possessions beside them for non-payment of rent. Households were overcrowded as the young couples and their children returned to live in the family home and there was real hunger and destitution.

This was the era of “hand-me-down” clothes, and of many other economies such as walking into Newcastle to save the tram fare, or even walking one section to save one penny. Through necessity, home haircuts were fashionable and usually some member of the family was adept at this task. My father was the barber in our household.

Rolled oats, bread and dripping and bread and treacle (dark syrup) formed the staple part of our diet. Each week a man with a horse and cart drove around our neighbourhood calling out “rabbit-oh, rabbit-oh,” and my mother usually bought a pair for about one-and-six. This was the only meat some families could ever afford. Another regular hawker, also with a horse and cart, called out: “Clothes propsss, clothes propsss, sixpence each”. The small suburban yards usually had a wire clothes line stretching from the house to the rear boundary and at least one clothes prop was required to support the wet washing. These hawkers would cut a load of suitable saplings in the bush and then drive around the suburbs until they were all sold. The horse and cart was a popular conveyance, and the “rag and bone man” regularly canvassed the district, calling for “aa-ny old ragss,” as did the “bottle-oh” calling for “eee-mpty bottles.” We children always kept a good look out for empty soft-drink bottles as there was a one penny refund, and this would buy a few sweets. Household bottles were always saved to sell to the bottle-oh.

Once a week the “fisho” would also go down our street and I was sometimes sent out to buy a pound of prawns. (This was our luxury cuisine as curried saveloys were more the norm.) The bread was delivered by horse and cart and the light draft horses used to know the run and follow the baker from house to house, saving him much walking. With all these horses on the roads a certain amount of manure was left, but it hardly had a chance to cool before some child was sent out to collect it for the home garden.

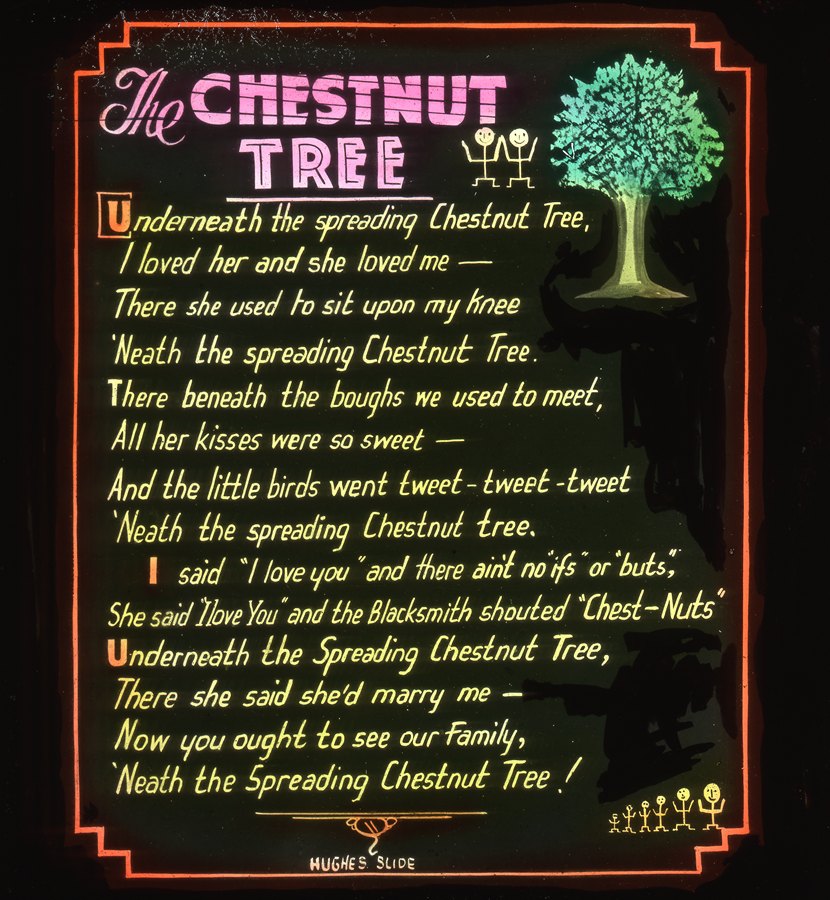

Dulcie aged 16

Dulcie aged 17

Dulcie in 2015

During these years most families had a safe for storage of perishable foods. However, as the economy improved ice chests, (the forerunner of household refrigerators for the working class) were again brought into use. The “ice-oh” would come through our suburb each day and he would have a load of ice on the back of his cart, cut into various sizes. He used ice-pincers to carry the block into each house where he would put it straight into the ice chest. If you were out the day the ice-oh was due to call, the back door was left unlocked and the money on top of the ice chest. Covering the block of ice with a bag was supposed to make it last longer and the ultimate economy was to buy ice only three times a week during the summer months. In winter the service was usually discontinued.

Down and out door-to-door salesmen were often very sad cases. They were usually trying to add a little extra to the dole, and dressed as neatly and tidily as possible in their threadbare clothing. “Buy some mothballs please missus.” At other times the caller might be trying to sell razor blades and shoelaces, or perhaps he wanted to “Sharpen your scissors, lady?” or “Mend your saucepans?” The trouble was that we were all down and out, and in our family all the ready cash was hoarded to spend on food and clothing. My mother was known as a good manager and she fed us to the best of her ability. Also, we were not in debt, as was the case with many families who had borrowed from money lenders to tide them over. They were to find that it took years to repay the debt due to the high rate of interest and the uncertainty of employment.

During the early thirties, at the height of the depression, a phenomenon occurred with the practice of “snowdropping.” In the inner suburbs it was unwise to leave washing unattended on clothes lines, especially overnight as these “snow droppers” would remove what they needed.

Before long my father was lucky enough to get work at his trade but some of this work was in the country so he could only get home at the weekend. His diabetes was always a problem as he was on a strict diet and had to inject himself with insulin night and morning. His condition was not really stabilised as he suffered from diabetic comas. At other times when his behaviour became irrational he had to be given a teaspoon of sugar and all his friends and workmates knew that he carried a small tin of sugar in his pocket for this emergency.

As the 1930s progressed money became a little more plentiful m our household. My sister had left school at 14 years of age and the only employment she could find was domestic work in private households for the munificent wage of five shillings a week. Many of these women exploited the young girls, extracting their “pound of flesh” and on one occasion my father had to rescue my sister from one particularly avaricious employer. Vera eventually found more compatible work but her experiences during the depression were more unpleasant than mine.

We finally had the electricity connected to our home and mum requested a wireless. This gave us great pleasure, especially when we listened to programmes such as Dad and Dave whilst washing the evening dishes. My mother travelled by tram to Newcastle once a week to go to the pictures, where she viewed a romanticised version of life, quite the antithesis to what she was experiencing. We children often went to the Saturday matinee at Herbert’s Regent Theatre on the corner of Beaumont Street and Maitland Road in Islington. I think it cost us about three pence admission and we were given one penny to spend.

A great morale booster during the thirties was community singing which was held in the city theatres. Admission was about three pence for adults and my mother often took Vera and myself. There was usually a pianist, and the words of each song were projected onto the screen. A lively compere would soon have the audience, mostly women and children, singing their heads off. This had the therapeutic effect of alleviating their often overwhelming troubles and producing happy faces.

For recreation my father enjoyed his regular Saturday night visits to the Newcastle Boxing Stadium, then situated in King Street near the National Park Street intersection. He was a member of the Waratah-Mayfield RSL where he found companionship and recreation, as was the case at the local hotel. My parents were avid readers of light literature, and lending libraries were situated in every suburb. A book could be borrowed for three pence per week and this provided a form of escapism for them.

Before long dad purchased another second-hand car, much to the disappointment of my mother who aspired to move from Islington into a better suburb and a bigger house. However, my father’s philosophy, “Leave deeds, not debts,” was later to prove its worth.

At this time we returned regularly to “Falsie” for holidays. However our car usually became bogged in the sand, whether we used the track from Anna Bay, or from Box Beach. Soon our humpy became derelict so dad bought a tent and we enjoyed many camping holidays at Nelson Bay. This was also a favourite place for a day’s outing when my parents visited the friends they had made during the early depression years, including the Asquiths of Fly Point and the Hunters of Nelson Bay.

There were still a few families living at Fingal Bay during the late 1930’s such as the Prescotts, Southwoods and Barrys. As the beach became more popular with tourists Arthur Elphick opened a shop in a converted bus. During World War 2 the American army was stationed at nearby Gan Gan Camp and the last of the squatters of Fingal Bay were evicted, their dwellings bulldozed and the beach taken over by the Army. Soon after the war ended land at Fingal Bay was subdivided and offered for sale, with the resultant development that is now evident.

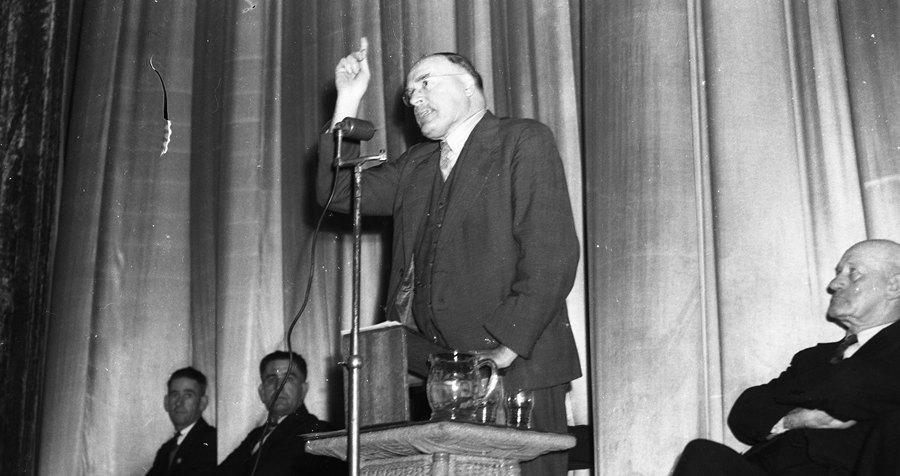

However, the years of the Great Depression had psychologically affected members of my family. Frugality had become a habit, as had “saving for a rainy day.” Savings banks were distrusted and politicians and political parties viewed with great cynicism. During my early days I had always heard heated political discussions between my father and his friends. They were of the opinion that during the early days of the depression politicians were not addressing the financial situation competently. When British economist Sir Otto Niemeyer advocated reduced government spending and repayment to Britain of all monies borrowed dad was highly incensed. Jack Lang’s bold plans for economic recovery were more acceptable to my father and the charisma of Lang was a great influence on the working class. After Lang’s dismissal my father joined the Communist Party of Australia. He never recovered from the demeaning experience of being “on the dole” and unable to feed his family, although willing to work. Dad had left England largely due to the class stratification system. He used to say that “he doffed his cap to no one” and this did prevail in Australia where we enjoy a more egalitarian society than in England. However, in the early days of the depression when food dockets had to be collected from the suburban police station servility was often demanded by these petty tyrants. Also, dole recipients were usually regarded as second class citizens by the more affluent.

With the outbreak of World War 2 my father commenced working on the open hearth at the BHP steelworks at Mayfield. I can remember many occasions when the soles of his feet were blistered from this hot work and I was given the job of pushing a needle and thread through the blister to “let it out” (allow the fluid to escape. It’s a wonder he didn’t develop gangrene!) In 1943 tuberculosis was diagnosed in Dad’s one sound lung, so he was admitted to Concord Repatriation Hospital near Sydney. It was there he died in 1944, aged 54. He spent his last weeks battling with the War Service Department which was of the opinion that he was not dying of war-related injuries. However, the medical profession thought otherwise and mum received a War Widow’s Pension after his death. As she was only 46, this proved to be of great benefit for she lived until she was 80.

In retrospect, mum told me that some of the happiest days of her married life were spent at Fingal Bay.