Coon cheese is finished as a brand. The most surprising thing is that it took this long. The brand’s owner, Saputo, has decided it will move with the prevailing tide of public opinion and change a name that some have perceived as racist.

And while it is certainly true that the name doesn’t have racist origins – it was named after famous cheesemaker Edward Coon – the company has evidently opted to take the same line so recently taken by other big food product makers. That is, if the brand-name is upsetting a growing number of people, then it makes more sense to change names than to keep arguing.

In recent times food multinational Nestle has announced it will change the names of its popular Redskin and Chico lollies, foreign brands including Uncle Ben’s and Aunt Jemima’s are being shelved, and big-selling Asian toothpaste brand Darlie (it used to be called Darkie) is also being retired. Eskimo Pie ice creams are going, as are some brands that feature pictures of native Americans.

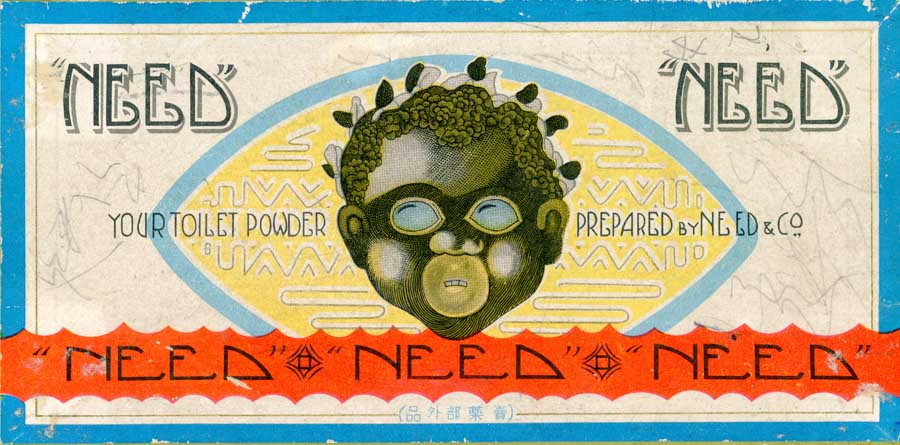

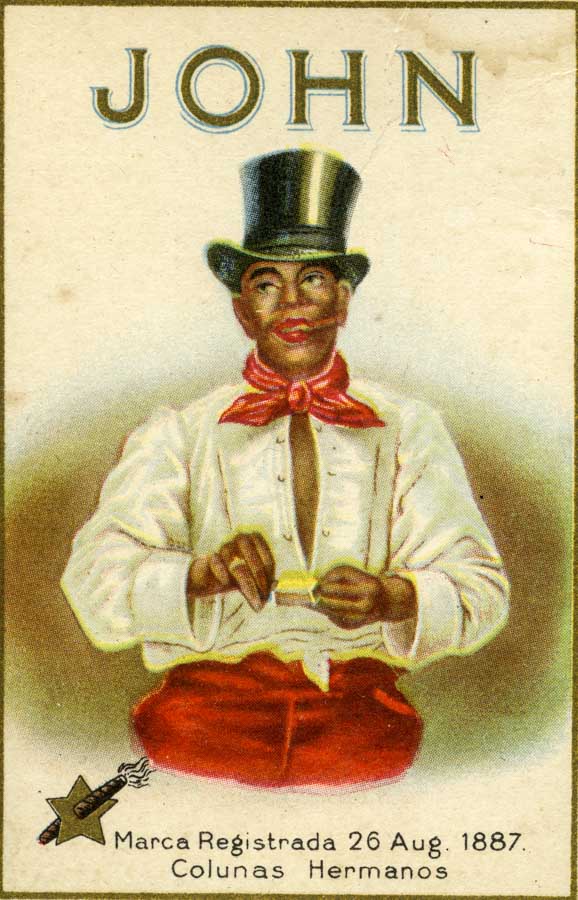

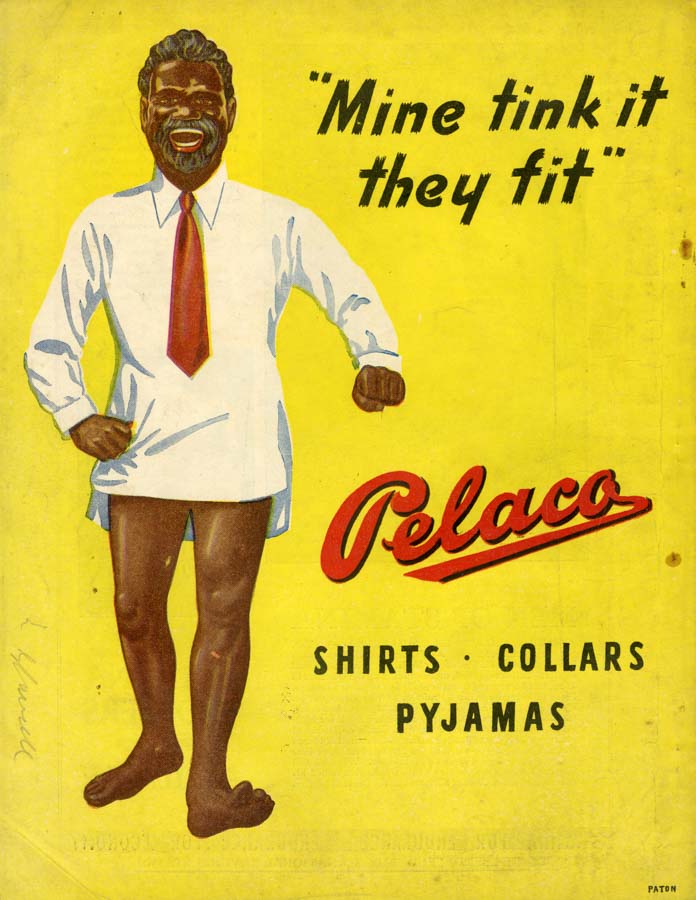

Advertising that overtly uses racist stereotypes is rare today, and the brands in question were hangovers from a time when that wasn’t necessarily the case. It was common in many places, including Australia, to use motifs representing black people – in particular – in branding and advertising as servile, not-very-bright and always eager to please.

.

.

.

.

It’s interesting to watch the media response to the recent brand retirements. Even Australia’s most rabid newspaper mastheads – which normally leap on any perceived opportunity to push a story that fits the formula “politically-correct nutters ruin everything” – have been far more restrained than they would have been if the name changes had been decreed by a government body, for example. The corporations involved are big advertisers, one might suppose, and they wouldn’t be walking away from long-established brand-names unless they believed it made economic sense to do so.

On social media, not surprisingly, the conversation over Coon cheese is livelier, and almost entirely based on the fact that the name wasn’t ever meant to be racist. On the other hand, many argue that the Coon family in question had apparently anglicised their name from the German “Kuhn” – presumably to blend in more easily with a community that might have had issues with German people. Such name-changes are very common. The original family name of US President Trump, for example, was “Drumpf” – although the question of when it was changed is debated.

Switch on your trannies

I observed a similar argument in a Facebook group recently when a person, presumably an older person, suggested that others might want to listen to a particular radio program and urged them to “switch on their trannies”. This caused a backlash from people who have never heard of transistor radios, but who are acutely aware of violence and discrimination against transgender people. The person who posted the item quickly changed the post, explaining their understanding of the word but also wanting to avoid offending people. But of course the argument raged on for a while.

It’s not hard to see the point of those who argue that the intent behind the use of a word is the most important thing, and that “tranny” and “Coon” when applied to radios and cheese have no ill intent. But then again, when you are on the receiving end of a derogatory name for long enough you will surely come to hate the sound of the word, no matter how it’s intended. When that’s the case those who use the word or are familiar with it are confronted with a choice. Does the word have such great importance for them that they feel unwilling to let it slip into disuse? Or is it inconsequential enough to let it go, and put the feelings of those who are hurt by the word foremost?

.

.

On that note I can’t help wondering about the locale named “Coon Island” at Swansea, Lake Macquarie, Australia. According to popular tradition – recorded authoritatively in Val Hall’s History of Coon Island, the place was named after a white man nicknamed “Coon” Heaney. The late Mr Heaney (real name Herbert Greta Heaney) was at one time the sole inhabitant of the island, which was consequently named after him. The history explains that Mr Heaney got his nickname because of his dark skin colour which came either from the coal dust of his employment or from the deep tan he acquired by fishing on the lake in the sunshine. There will be some, perhaps, who believe Coon Island should keep its long-standing name. Others will certainly argue that the name has outlived its usefulness and might helpfully be retired and relegated to history.

Language is changing, as it always does and as it always must, reflecting changes in the way societies think, in the way they see themselves and in the way they want to see themselves. These changes are almost always slow, and they seldom win unanimous support. What we must hope, above all, is that the goal that underlies the often-symbolic arguments over particular words is kept at the forefront. The best world will be one where race and gender are no longer perceived as battlefields. In that world, prisons won’t hold disproportionate populations of some racial groups and lack of employment and educational opportunity won’t be linked to skin colour.