Wickham residents were startled by a loud explosion at about 2pm on Saturday, December 16, 1939. Within moments the cause was clear: one of the huge fuel storage tanks owned by Commonwealth Oil Refineries near the waterfront had caught fire and was burning ferociously, sending huge black smoke clouds into the sky. Those who recalled the suburb’s earlier scare with the fire on the oil tanker British Honour in 1930 scrambled to get their families and belongings out and away from the danger zone.

A signalman – J. Sommers – at the Hannell Street railway box heard the noise too, and felt the ground move. He couldn’t see the burning kerosene tank, but he could see the smoke and lurid glare of the flames. The signal box had not long before been connected by direct phone line to the city’s Fire Brigade headquarters at Cooks Hill, just so that the signalman could help ensure easy access across the line for rushing fire engines. This time the line was useful for another reason. The signalman’s call was the first the fire brigade knew of this potentially disastrous fire.

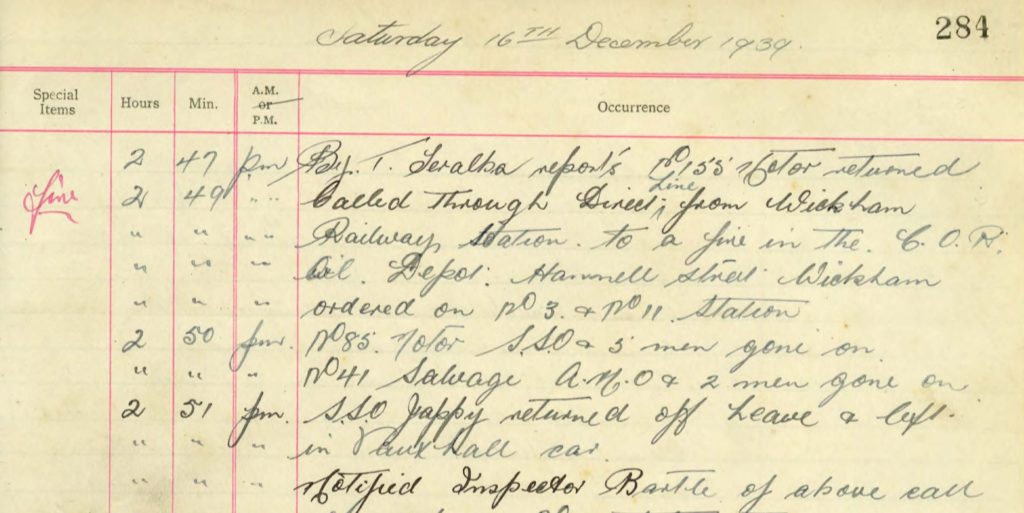

Fireman Barry Magor – son of another well-known fireman, Ken Magor – has the original incident book from Cooks Hill Fire Station, setting out the sequence of events from the perspective of the fire brigade. The entries for December 16 start peacefully enough, with the usual mundane burn-offs, roll-calls and equipment reports, but from the point at 2.49pm when the call about the fire came through the day becomes frantic indeed. You can see the pages in PDF form here.

In the explosion that preceded the fire an oil company engineer, Maxwell Reybourne Nathan, 35, was killed. His body was found 50m from the explosion site. The fire was a big challenge for firefighters, who had to keep the other nearby fuel tanks cool so they didn’t also catch fire, while also somehow managing to get fire suppressing foam into the burning tank. The heat was extraordinary, and the roaring of the blaze was described as deafening as the firemen pumped millions of litres of water from a street hydrant and from Throsby Creek. Those fighting the fire up close had to be constantly sprayed with water, while everybody prayed that the tank would not collapse. It was considered lucky that the tank’s roof had blown off at the beginning, and also that the tank had been welded and not riveted. Firemen were unable to simply play water on the flames, since the water would have sunk below the burning oil, raising its level and making the danger even more severe.

Meanwhile, hordes of onlookers flocked to vantage points, creating a problem for police who were trying to keep people away in case of a bigger explosion. One onlooker was an employee at the Newcastle Kodak film lab, keen photographer Russ Hughes, who took a number of shots on 35mm film.

It soon became apparent to the firefighters that their best chance to stave off disaster was to pump fire-suppressing foam into the top of the tank, but unfavourable winds made this impossible until a 30m ladder was brought and brave firemen, putting their own safety last, clambered up next to the inferno. It took time to get the ladder in place since the ground around the tank was soft and wouldn’t carry the heavy fire engine. By the time the foam was ready to be pumped into the blazing tank its walls had begun deforming. Fortunately, the foam began working almost immediately, forming a thick blanket over the top of the kerosene and cutting off the fire’s oxygen supply. Firemen worked in relays of three, pumping in foam while the top of their ladder became charred from the heat. As a matter of interest, the foam product, known as “Foamite” had glucose and licorice powder as two of its main ingredients.

The fire was put out after four hours, but it prompted renewed calls for the oil tanks to be moved away from residential areas. Authorities insisted, however, that the risks were too small to justify the trouble.

While the fire was taking hold an oil tanker in the harbour nearby – which had been preparing to discharge a cargo into the tank, was hastily removed to safety.

The fire on the British Honour, 1930

No doubt many were recalling an earlier fire, the blaze aboard the oil tanker British Honour, at the nearby oil berths on February 24, 1930. This fire had been attended by the same fire brigades and it was reported that some of the same firemen were at both fires. Experts asserted that the ship fire was the more dangerous. This was probably the case for the firemen, who had to go below decks when bulkheads were bulging from heat and an explosion had already blown the ship’s bridge away.

The British Honour was a fairly new tanker, only about two years old, when it made its first, fateful visit to Newcastle. It was about 9am when people reported hearing an ominous rumbling and flames were seen to burst from the ship. A pall of black smoke rose into the air, summoning hordes of onlookers . The crew rapidly abandoned ship, with only a handful suffering injuries to their feet caused by jumping ashore.

Police tried to hold back the crowds, but the onlookers pressed in and some suffered burns when a series of explosions ripped through the ship, culminating in a very loud one at about 10.30 am. Following this explosion, flaming debris rained down and some spectators were hit. Fireman hurried to the wharf and played streams of water over the ship. For some time, 10m flames roared from the affected tank. It was claimed that safety valves prevented the ship’s total destruction.

Terrified children were evacuated from nearby Wickham Public School, and a racehorse which was being swum near a jetty close by was blinded and maimed by the fire and had to be be destroyed.