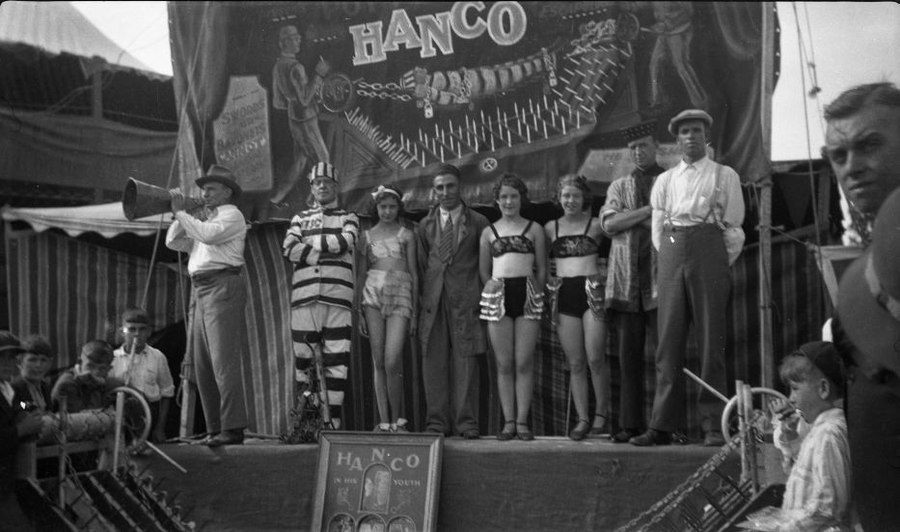

When my friend Pete Smith decided to recreate a photograph originally taken by his grandfather, Syd Smith, at Maitland Show in 1924, he asked me to stand in as the “star” of the picture. The only star quality that rendered me suitable for this honour was the habitual frown into which my face tends to relax. That somewhat unhappy cast of feature apparently makes me resemble the man known as “Hanco”, whose escape act features in the vintage photo.

Naturally, being asked to stand in for Hanco led me to wonder about him. Who was he? What was he like? What can be discovered about his career as a showman and vaudeville performer? At this stage, I’m sorry to say there is not much information readily available. Still, there is some – enough to whet the appetite – and I find myself now with another long-term project on my hands: to find out all I can about this Antipodean Houdini before I am called upon to step in front of the camera sometime in 2024.

Syd Smith’s photo, shared years ago by Pete on the internet, has turned up on the website of a Houdini and escapology enthusiast in the USA who has presumed to place his own copyright watermark over the image. I can vouch, however, for the photograph’s provenance, since I have had the privilege to scan Syd Smith’s negatives.

By the time Hanco posed for Syd’s photo at Maitland in 1924, he had been working as an escapologist and quick-change artist on the Australian and New Zealand entertainment circuit for the best part of 20 years. Interestingly, he was not the first (or last) to use the name “Hanco”. One predecessor was English stage performer Theodore Bernstein, who billed himself Hanco the Handcuff King in the early 1900s. According to some reports, he dressed as a prisoner and told audiences that he had learned his tricks in jail. This British Hanco killed himself with a table knife on January 18, 1906, aged 35. An inquest in Liverpool ruled he had been temporarily insane, apparently depressed because of ill-health and a lack of engagements. The American stage magicians’ journal Mahatma laid the blame for his death on two British managers whom it accused of having a grudge against “an American handcuff king, on whom they made thousands of pounds weekly, but when he accepted contracts for an opposition firm, they hired a cringing associate of thieves, also a man – who is known to have been implicated in several burglaries – with this companion”. “This action on their part only served to add to the American’s reputation and had a tendency to hurt the poor underpaid imitators – some of whom were previously earning an honest livelihood at other trades,” Mahatma editorialised. While knowing little of the circumstances, I can’t help suspecting this piece of commentary may have been mostly intended to further inflate the reputation of America’s prize escapologist, the famous Houdini. Another unsourced account asserts that the British Hanco had made the mistake of revealing the tricks of escapology on stage and thus made himself subsequently unemployable.

Naturally, the great Houdini (real name Ehrich Weiss) is an important part of the context to this story. Houdini began his escape routines in the USA in about 1900 and became a global touring sensation, spawning numerous imitators. Thanks to Houdini’s amazing escape stunts and equally amazing talent for self-promotion, similar acts were very popular in the early 1900s, with numerous people putting themselves forward as practitioners of the art – wriggling free from ropes and handcuffs and performing more elaborate escapes as stage entertainment.

As far as “Hancos” are concerned, the earliest reference I’ve found to escapologists using the name in Australia is in Sydney’s Evening News on April 3, 1905, where “the Hanco Brothers, Handcuff Kings and Gaol Breakers” were on the bill at a charity show at the Gaiety Athletic Club as part of an entertainment troupe managed by promoter Bert Howard. The Hanco Brothers were said to have been “discovered” by Howard, who was reportedly planning to take them, along with two fighters he apparently managed, to the Maitland Show in 1905, where they were reported to have been successful in handcuff escapes. Later, Howard was accepting substantial financial challenges from people who wanted to test the escape skills of the Hancos using “chains, handcuffs, locks etc”.

I don’t know if the Hanco of Syd’s photograph was one of the Hanco Brothers reported in 1905, but he may well have been. Our Hanco begins to appear in press reports on Trove from 1909 and his real identity is revealed in an article in the Australian magazine The Theatre in its issue of October 1, 1910. He gave his name as Cook, self-described as “a Victorian native, and the son of Dr [Charles] Cook, who is practising in Victoria at the present time”. He had “drifted” into show business about eight years before, he said, and was hoping to tour America with his escape act.

In fact, the performer widely known as “Sam Hanco” was Samuel Phillip Cooke. A small amount of additional information about him is stored in the Alma Conjuring Collection as the State Library of Victoria. He is reported to have married show performer Dorothy Guest (who used the stage name Dora Marlowe and performed as part of an act called the Marlowe Sisters) on July 30, 1912, at Brisbane. Dorothy was reportedly “the second-eldest daughter of Frederick Guest, of Melbourne.”

A transcript of a 2000 interview with Great War digger Raymond Durston mentioned Hanco (Private Sam Cooke) being in uniform in wartime, participating in shows and concerts for recruiting purposes. According to National Archive records, Sam Cooke was born at Prahran on October 17, 1878. At the time of his first enlistment in Sydney in February 1917, (he signed up twice) he was living at Darlinghurst and had two children with Dora, one of them aged three. He didn’t last long in uniform. Bunions on both feet made it impossible for him to march and drill and caused him to be a “constant attendant at sick parades”. He drew his last army pay on June 15, 1917. His next enlistment – this time for overseas service – was on March 22, 1918, at Footscray. It was at this time that he performed with recruiting parties, until he was sent overseas aboard the Barambah on August 31, 1918. He caught influenza on the ship on the way to England, missed active service (the war ended on November 11, 1918) and was sent back sick to Australia aboard the Karoa on March 28, 1919. He was finally discharged on medical grounds on May 22, 1919.

As escape artists go, Hanco seems to have been a very good one. He already had a fine repertoire of acts when the great Houdini took Australia by storm in early 1910. Indeed, with at least one routine he appears to have beaten the American master to the punch. It seems plausible that Houdini’s heavily promoted tour of Australia whet the appetite of Australian showgoers for similar escape acts, open the door for Hanco to thrive.

Hanco’s routine escape act involved wriggling free from straitjackets, handcuffs, chains and ropes. He often challenged members of the public to tie him up and he went to great pains to have witnesses check the knots to preclude cheating. The only locks he admitted being unable to defeat were the Chubb brand. Sometimes his audience volunteers were too enthusiastic and thorough for Hanco’s liking. In 1911, having asked volunteers to buckle up his straitjacket, Hanco was dismayed when one of them also tied knots in the straps to make life harder for the escape artist. Warning the volunteer, Arthur Cummings, that he would “knock him to Footscray” when he got free, he made good on his threat half-an-hour later, putting Cummings in hospital for three days. Hanco pleaded not guilty, suggesting some of the boys in the lane might have got to Cummings, but the judge fined him 20 shillings.

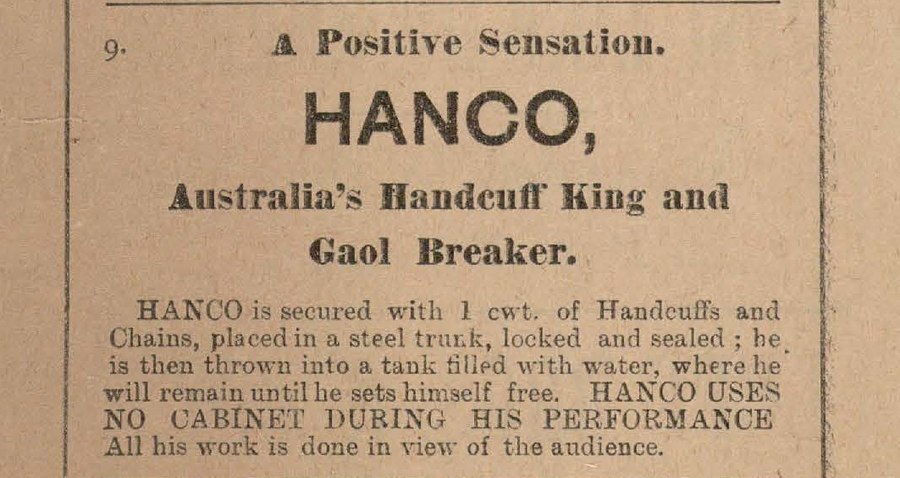

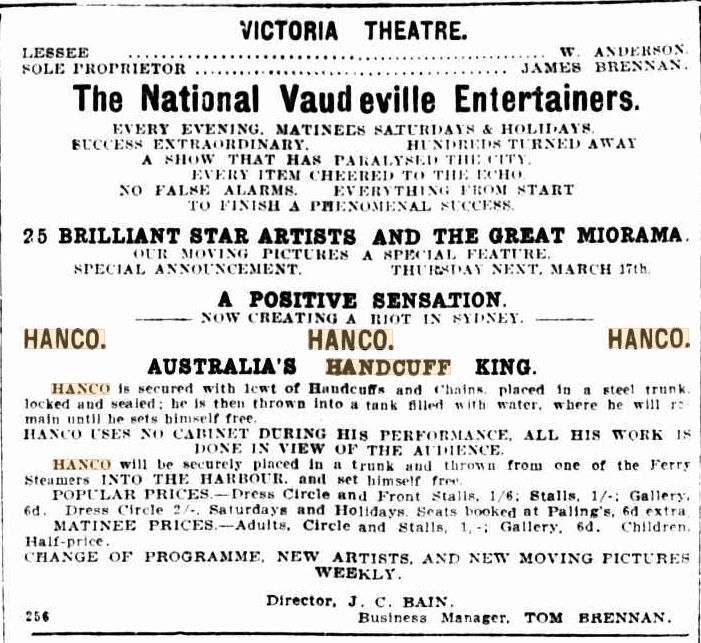

A favourite Hanco act was to be handcuffed, leg-ironed, jammed into a small trunk and immersed in water. He tried his hand at bullet-catching and quick costume-change acts. One of his signature routines involved an apparatus named the “Spanish maiden-crusher”, a coffin lined with sharp spikes into which he was locked, head down, only to emerge in less than 10 seconds wearing a completely different costume. Another was his “human submarine” act, in which he was placed in stocks, cuffed and dropped head first into a 3m deep tank from which he would escape in about a minute and a half. In still another act, Hanco would dive from a height of 40 feet into six feet of water and swim underwater for 90 yards.

In 1911 The Sydney Morning Herald described a Hanco act:

Hanco, the handcuff king, whose boast it is that he can escape from any bonds successfully, defied the attempts of Messrs. F.W. Hertle and M.C. Brennan, two of his challengers, to keep him in durance. The terms of the challenge called for three tests. The first was the regulation strait-jacket, but with this addition, that the challengers were to have the right to rope Hanco after enveloping him with the jacket. With his arms crossed on his breast, and trussed up like a fowl, he certainly did not appear to have an easy task before him. After a few seconds preliminary wriggling and rolling, however, he succeeded in getting his arms free from the enveloping rope, and soon afterwards released his arms. After that the rest was easy, and in rather under seven minutes Hanco, holding the rope and jacket in his right hand, was bowing in his shirt sleeves to the audience. The second test appeared even more difficult. A small rectangular iron rack was placed endwise on the stage. Hanco was handcuffed and leg-ironed to it. Then a heavy iron chain was twice passed round his neck and fastened tightly to the top bar of the rack. With a meaning smile on his face, Hanco withdrew his hands in quich succession from the handcuffs as easily as, or perhaps it would be more correct to say, with greater ease than the majority of women take off their gloves. The chains were quickly removed from his neck, and then with a couple of almost contemptuous motions, he withdrew his feet, still slippered, from the leg irons. Again there were thunders of applause. Seeing that Hanco had so easily found their two previous attempts to secure him, his challengers, acknowledging defeat, decided to dispense with the third test.

It wasn’t always that easy. A Dunedin (New Zealand) newspaper reported:

Hanco, the Handcuff King, while doing the Fuller Vaudeville Circuit, was beaten by two young experts at Dunedin. They tied him with a long, strong rope, which, having a “policeman” grip above both elbows, pinioned his right arm to his chest, and the left to the small of his back. A couple of turns around his neck prevented his arms from moving down, and the turns being tight round his thighs, prevented an upward movement; the elaboration of

coils round his arms and body did the rest. Hanco gave in after a two hour struggle.

At Kalgoorlie in January 1911 he also had a tough time:

A more exciting feat was the way in which Hanco freed himself from ropes placed around him by Messrs. Dwyer and Shilinsky, miners on the Perseverance Gold Mine. With ropes tied on every limb and in every way that could be thought of to operate against any movements that might be made, it seemed certain for several minutes that Hanco had essayed a task that was beyond his powers, but by the use of great strength he strained the sash cord that was used on him until he could lie at full length, a position which he won, although his legs had been tied back towards his head. At last Hanco got one arm free as far as the elbow, and he worked until the other was also free and useful, after which it was only a matter of untying knots until he again stood a victor before the audience. The last section of his wonderful show was clone in a tank containing several hundred gallons of water. Prior to this he was handcuffed with a pair of double-lock, figure-eight, eight-ratchet handcuffs (which were obtained at the Kalgoorlie police station), and leg-ironed in a, style that suited the vigilance committee, who then dropped their man into the tank, where he remained for three or four minutes, a period which was full of excitement for the audience, who seemed to recognise the dangerous nature of the act. Hanco was obliged to come to the surface several times for air and return to his work. At the end of the time stated he was assisted out of the tank holding the open handcuffs and leg-irons up to the gaze of the audience, who applauded vigorously.

At Barcaldine in February 1913 he walked off the stage in disgust after some heckling:

Hanco was announced to do the trunk and tank act; that is, to be locked in a trunk and thrown into a tank of water. After some difficulty he freed himself from some fastly-tied ropes, during which process some of the audience called out “Hurry up” and “Do you want a knife?” Hanco then left the stage, saying he would proceed no further.

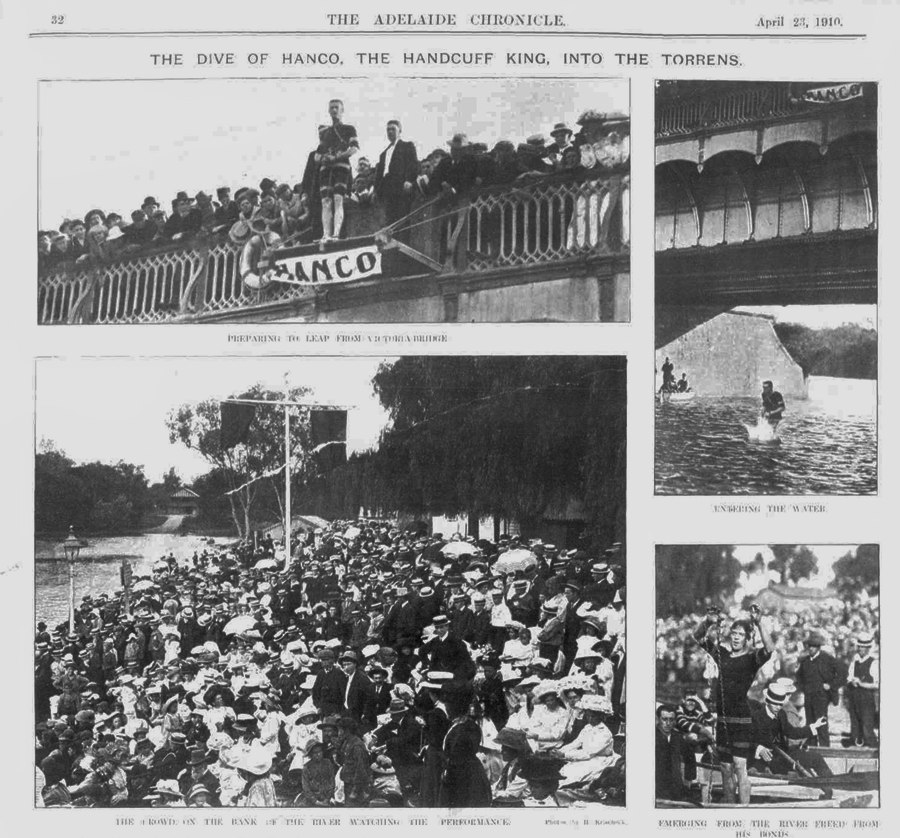

Hanco got a lot of publicity for his plunges into rivers, preferably from high bridges. He would be chained up, then would dive into the water and rapidly free himself. Performing at Maitland Town Hall in August 1910, Hanco did his usual escape routine, but begged off the advertised “trunk and tank” escape, saying he had caught a chill after diving into the Hunter River from the Belmore Bridge that day. He promised to come back another day, when he would be “bound and placed into the mouth of a cannon, from which he would be fired some 30 feet into a tank of water, prior to which he would succeed in removing his manacles”.

Being lowered into a river while bound inside a trunk was the stunt for which Hanco has been credited with stealing a march on Houdini. When the stunt went well it was a sensation, but on one occasion at least it went badly wrong, as the Wagga Advertiser reported in February 1910:

The performance arranged to take place at the Hampden Bridge yesterday afternoon, when Hanko, billed as Australia’s great handcuff king, was to be locked with handcuffs and leg irons, and placed in a trunk and lowered into the water to remain there until he freed himself, was a complete fiasco. A huge crowd assembled which lined the banks of the river on either side, and before the time for the performance Hanko’s colleagues were very busy with collecting boxes, and apparently reaped a rich harvest of coin. Hanko was well bound with irons and chains, and was put into the box, which was afterwards locked. Before it reached the water, however, the lid burst open and Hanko was revealed inside free from all encumbrances. “The box has busted”, he called out to his helpers on the bridge, and so the great crowd moved away disappointed with the outcome of the afternoon’s holiday.

Hanco’s act struggled on during the war years, until his enlistment(s). Postwar it evidently took time for the show circuits to recover and Hanco never regained his former profile. He continued to work, though perhaps mostly on the travelling carnival circuit. In 1933 at Mordialloc he was billed to “endeavor to free himself from a straitjacket while manacled and tied at the ankles and suspended 70 feet in the air. After releasing himself, Hanco will dive through a sheet of flame, into a tank of water.” At the 1938 Altona carnival he was billed to escape from a straitjacket while hanging from a tall pine tree in a public park. He would have been pushing 60 by then, and it can’t have been easy. (That’s assuming it was the same Hanco.)

There was at least one other “Hanco the handcuff king” working in Australia. Another Hanco – real name James Harris – was jailed in 1922 in Tasmania for robbery. It was apparently not a first offence.

Fascinating show people! But where is the photo with you standing as Hanco ?

Not taken yet 🙂

Great post Greg!