It’s a tricky business, naming modern-day edifices after long-dead people. You might have an idea in mind that your candidate was a solid citizen with many outstanding virtues, but it’s often worth checking just in case there’s a skeleton or two in the closet. The John Hunter Hospital in Newcastle, NSW, offers a couple of examples.

I was health reporter for The Newcastle Herald at the time the John Hunter Hospital was opened, and I recall a suggestion by the health board chairman that the hospital be named the “Johns Hunter”. This was, I think, a forelock tug to Johns Hopkins University in the USA, but mostly a reference to the fact that there were three John Hunters the new hospital was being named after. There was John Hunter the former Governor of NSW, after whom the Hunter River and entire Hunter Region – of which Newcastle is the unofficial capital – was named. There was John Irvine Hunter, an Australian anatomist who died in 1924 at the age of 26, having already been appointed the youngest anatomy professor at the University of Sydney. Then there was the other John Hunter, the 18th century “father of scientific surgery”.

In recent years some clouds have begun to gather over the reputation of this John Hunter, with some scholars suggesting that the corpses of near-term pregnant women used in the compilation of his brother’s master work The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, may have been obtained through sinister means.

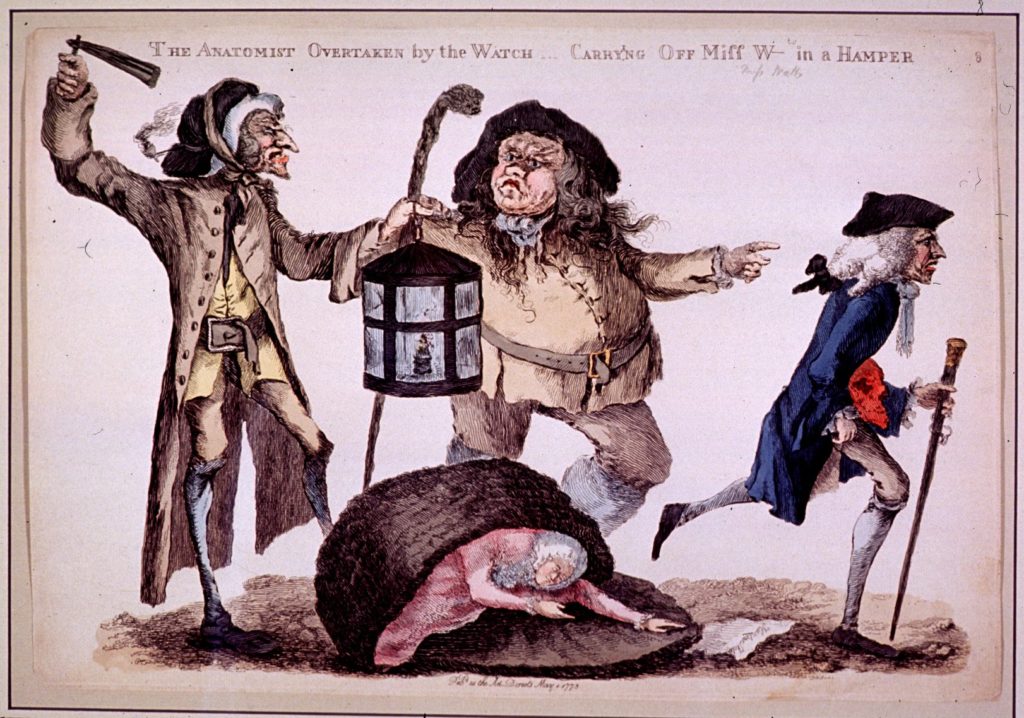

John Hunter, who was born in Scotland 1728 and died in 1793, went to London at the age of 18 and got a job with his famous older brother William who had made his name as an obstetrician, anatomist and surgeon. The elder Hunter had a thriving practice and a very popular school of anatomy and surgery. Young John showed a special aptitude for dissection and as such was a great asset to his brother’s business. Part of his job was liaising with the procurers of bodies for dissection, including the so-called “resurrectionists” who raided graves to meet the hectic demand for bodies from anatomy schools. The Hunters’ school was especially demanding, since it provided each student with their own cadaver for lessons, instead of merely letting the students watch the teacher do the dissections.

The profusely illustrated book on the pregnant uterus contains images of twins in utero, with a note by John Hunter that accused the dissector in the case of having procured the body without the authors’ knowledge, adding that this was “the cause of a separation between them, for the leading steps to such a discovery could not be kept a secret”. It is suggested by Hunter’s modern-day critics that corpses of near-term pregnant women were extremely hard to get, and those carrying twins even more so, so the “leading steps” must imply whatever activities were involved in getting the body. The comment makes it plain that the authors would have preferred those steps to have been “kept a secret”.

Given the tempting prices paid by anatomy schools for cadavers, it is no surprise to learn that some providers did the killing themselves – most notably the infamous Burke and Hare. Indeed, smothering a person to death with a view to selling their body is called “burking”.

It must be noted that other academics have argued strongly against the allegation. They point out that the book was assembled over a number of years, so the pregnant corpses might well have been acquired with no wrongdoing.

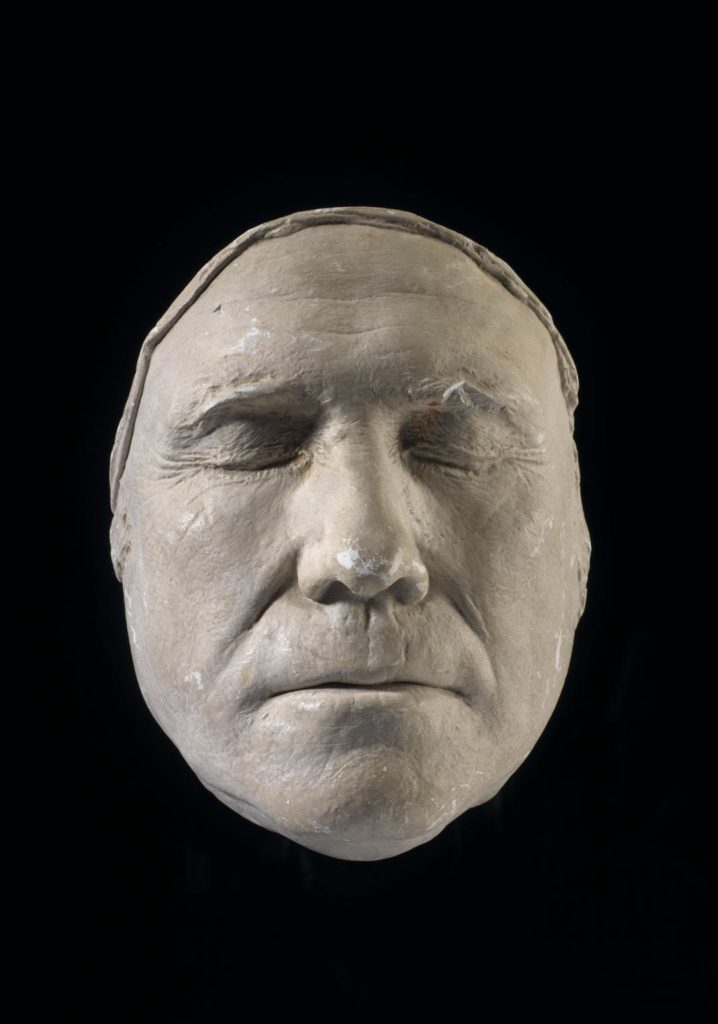

But it’s beyond doubt that John Hunter’s personal ethics in the area of corpse acquisition are open to question, given the well-known case of Charles Byrne, the “Irish giant”. Byrne had a disease that caused him to grow extraordinarily tall, making him a celebrity across Britain. Hunter made it known he wanted Byrne’s body when he died, but Byrne made it equally well-known that he didn’t want to be dissected by Hunter or anybody else. When he knew he was dying Byrne paid his life-savings to ensure he was buried at sea, away from Hunter or any other body-snatchers. But Hunter bribed enough people to ensure he got Byrne’s body anyway. He stripped the skeleton bare and put it on display in his famous museum, which was packed with a myriad anatomical specimens. The remnant of Hunter’s museum, now in the hands of the Royal College of Surgeons, still features Byrne’s skeleton, despite numerous calls to do the decent thing and bury it in accordance with its owner’s wishes.

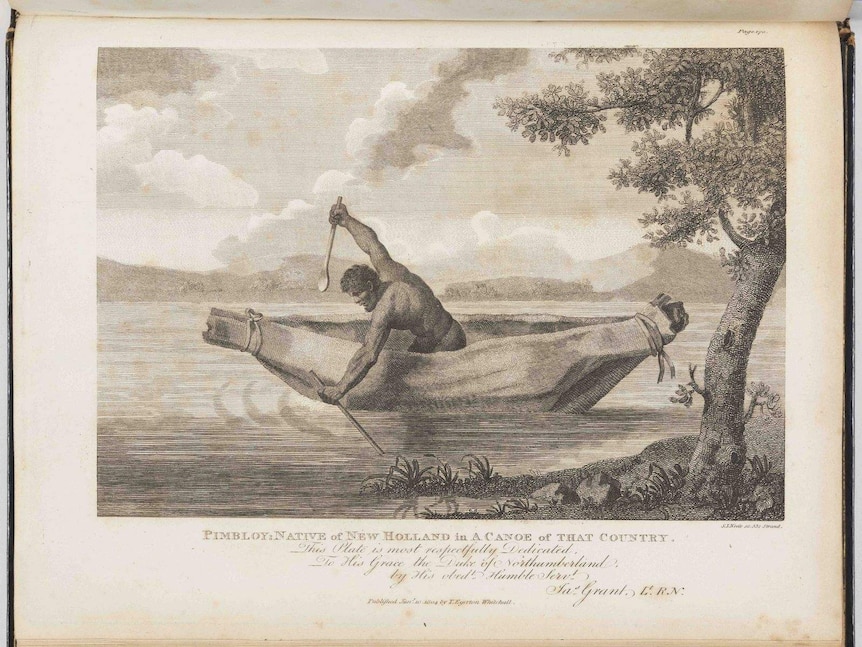

Hunter made an outstanding contribution to medical science. He was also a very strange man who led a remarkable life. He joined the army for a while to get more practice at trauma surgery. He conducted literally thousands of dissections of humans and animals, did many bizarre experiments – some of which were definitely cruel, like deliberately promoting miscarriages in pregnant dogs – and even used himself as a human guinea pig, injecting himself with various infectious agents including gonorrhea and syphilis. He had a large private zoo, stocked with living creatures from all over the world.

Hunter was a friend of both Captain James Cook and Sir Joseph Banks – the famous promoter of Botany Bay as a destination for British convicts – and when Banks was sent the head of Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy in 1802, he thanked Governor King for the gift, which he wrote was “very acceptable to our anthropological collectors and makes a fine figure in the museum of the late Mr Hunter”. Requests for the return of the skull of Pemulway, “the Rainbow Warrior”, have met with the reply that it appears to be lost – perhaps destroyed in a World War 2 bombing raid.

I suspect this John Hunter would have been bemused to learn that a hospital in New South Wales had been named at least partly in his honour.

Now for the runner-up

Former commandant of the penal settlement at Newcastle, Captain James Wallis, has the peculiar distinction of almost having had a hospital building named after him. Hunter New England Health was planning to name its relocated Royal Newcastle Hospital services after Wallis when the services were shifted to a new building at the John Hunter Hospital campus. The plan to name the building after Wallis stalled when objections were raised on behalf of Aboriginal communities.

Historical documents showed that Wallis had in 1816, before coming to Newcastle, led a punitive expedition against some Aborigines near Appin. Wallis had been sent by then governor Lachlan Macquarie to punish the tribes who had stolen corn and potatoes from white farmers. His official journal records the chilling event in disturbing detail. The Aborigines were camped near a cliff top when a crying baby gave away their position. Wallis and his armed men sent in dogs and the blacks panicked and fled. The soldiers started shooting, killing seven. Seven more plunged over the cliff in their terror and were killed by their fall. The bodies of 14 men, women and children were recovered and Wallis took their heads back to town (as he had been ordered to do) to prove he had done his job.

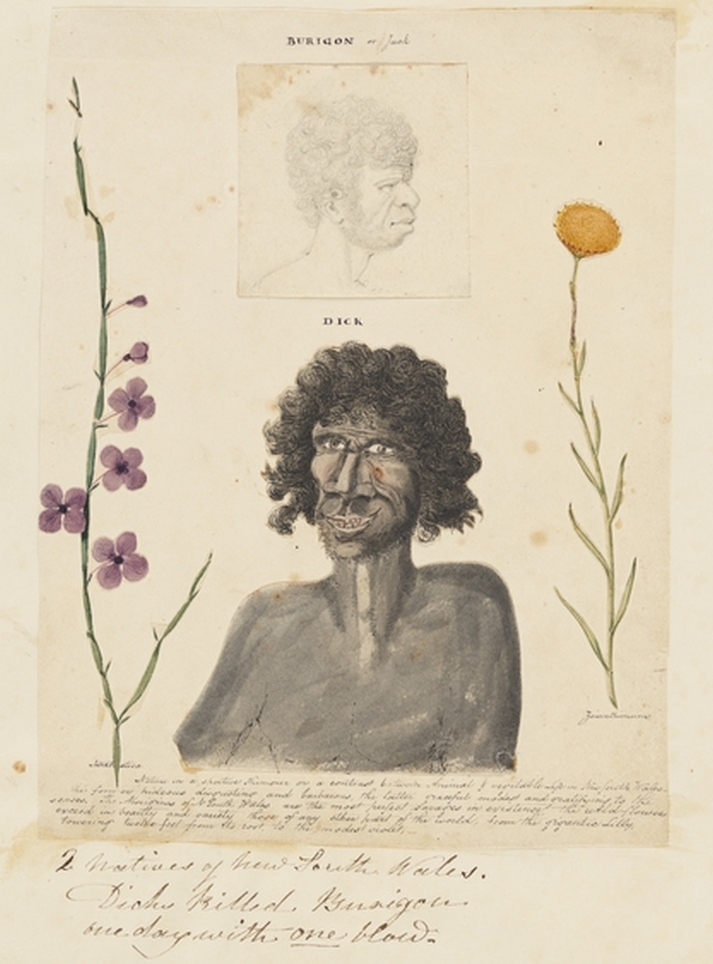

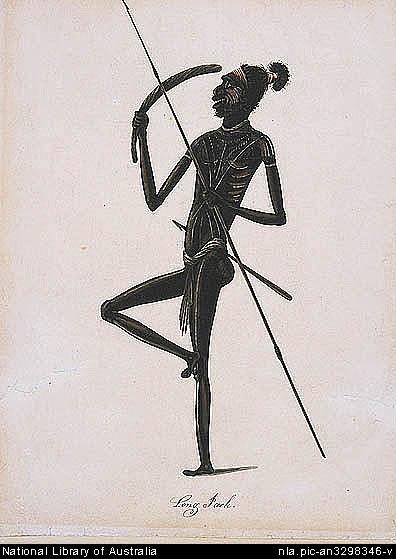

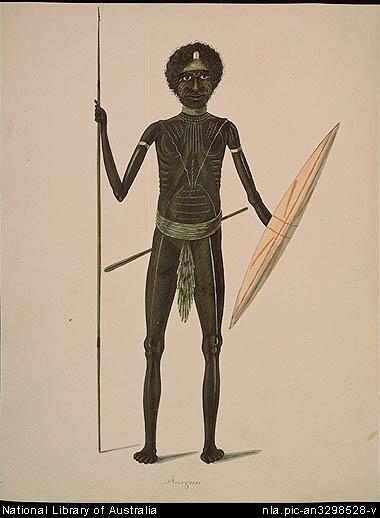

The exposure of these facts to the general public immediately cost Wallis his posthumous hospital naming rights. Clearly, he was complicit in a terrible atrocity. But, as usual, matters are not completely clear-cut. A monster he may have been in his actions at Appin, but a page of his writing, found in a book in Canada, reveals a man of some sensitivity, capable to some extent at least of appreciating the qualities of the strange new land in which he found himself and also those of the Aborigines he came personally to know. The short piece of writing describes two Aboriginal brothers, Burigon (also known as Jack), “a chief of the Newcastle tribe”, and his brother Dick. John McPhee, the Sydney historian who located the document, said it had been in an album that had belonged to Wallis’s widow. He learnt of its existence through a dealer, found out who had bought it and had asked the owner for a copy. The owner had happily agreed.

The piece of prose was written to accompany two sketches Wallis drew of the men. Its content, in edited form, says:

Burigon (commonly called Jack) was the elder & chieftain of his tribe. He was a keen shrewd fellow attached to me and to the Europeans generally from interested motives, for we often administered to his wants. Though they are not so numerous as ours, still savages have theirs, a tomahawk, a fish hook, tobacco, sugar, kangaroo and in cold weather a blanket were objects of Jack’s ambition.

Often when hungry he has said to me, “Massa shoot crow for me to Paata”. When the bird fell the process was very simple: thrown on the fire, the feathers were quickly scorched. To rub them off, tear open the body, take out the entrails, give it another cast for a few moments on the fire, and then devour it, was all quickly performed and satisfied for the time Jack’s appetite.

He was tall and gaunt, very expert with this waddy or club. ‘Twas his scepter and with the prowess of arm, sustained his kingly dominion. I once witnessed its power. He came and told me he had got a second wife and I congratulated him and asked how Mary his present wife would like it. He answered very well, that she was “murrybodgeree”, very nice girl.

In a few days he came to me in much distress to say his “beautiful his blooming” had been taken from him by his brother Dick and sought my influence to recover her. I declined, as I never interfered in their disputes. The following day I was near our barrack and Jack with me when the lady’s appearance with Dick raised a storm. Jack seized her by one arm and Dick by another. She threw herself on the ground and to save her arms from being torn from her body. I interfered. I then told her to go where she pleased. When seeming to prefer Dick, Jack appeared satisfied in bestowing a few thumps in an awkward manner on his brother and Jack was walking off, when Dick drawing his “wamsa”, threw it with all his force and unerring aim. It struck his shoulder, stung with the pain and irritated by his treachery, Burigon turned around & taking his fatal Waddy from his belt, he struck his brother one blow on the side of the head. ‘Twas enough. He fell and was borne away senseless.

Burigon came to me next morning in distress to tell me his brother Dick was “murky” (dead) and that his tribe would kill him. I advised him to remain in one of my out offices until the storm had subsided. He did so for a short time but appeared to pine away so at separation from his people that, determining to brave the worst, he left me. For a few days he remained away and then returned a frightful object, his matted hair and dark face all clotted with blood and his skull fractured in a most dreadful manner. He again took up his old abode. The surgeon to the settlement kindly bound up his wounds and he recovered his health and peace of mind at the same time for this had assuaged the wrath and reconciled him to his subjects. He had however a secondary punishment to stand from the neighboring tribes. He however did not appear to dread their vengeance so much and arming himself with a large wooden shield which he begged from me he sallied forth and returned in some days unhurt after having stood his punishment and having escaped unhurt.

Jack dived like a waterfowl. My dogs once returned to me with every appearance of having killed a kangaroo. He tracked in the direction they came from until we found a small deep pond. Jack said “I believe kangaroo here Massa”, and dashing in soon disappeared. He remained under water until my suspense amounted to anxiety when at length his black face appeared with a smile of triumph and he held above the water a fine large kangaroo.

. . .There are scenes in all our lives to which we turn back to with pleasurable, though perhaps with a tinge of melancholy feelings, and I now remember poor Jack the black savage ministering to my pleasures, fishing, kangaroo hunting, guiding me through trackless forests with more kindly feelings that I do many of my own colour, kindred and nation.

Jack proved his attachment and confidence by giving me his only son a fine boy ten years old to be sent to the native establishment formed at Parramatta by the late benevolent and truly philanthropic Governor Macquarie.

Jack’s career has been, I understand, since terminated by a treacherous stab from a convict who by his execution soon after paid in this world the forfeit of his crime, and was the first European that suffered for an Aboriginal native of New Holland.

Dick was a shrewd active fellow but wilder and more untamed than Burigon; he appeared drowsy and fatigued as I copied his face, faithfully though without art. “Dick,” said I, “suppose you murgi (die) where will you go?” He hesitated for some time. “I don’t know Massa, but,” (and he significantly pointed down), “I believe I go to hell.” Poor Dick was soon after made wiser than I can pretend to be.

Wallis’s information about Burigon’s death was correct. The chief was killed by runaway convict named in official records as John Kirby. An 1821 letter from the Rev Samuel Leigh to the Wesleyan Missionary Society described “Burgon” or “Long Jack” as “a sensible and intelligent man”, and noted that “a few months back whilst on an excursion [to apprehend runaway convicts]”, he “was cruelly stabbed to the heart by a bush ranger who has since been apprehended, tried and convicted of the murder and executed for the same”.

An exceptionally detailed account of the murder of Burigon can be found here, at the University of Newcastle’s Living Histories site.

As for James Wallis, he attained the rank of major by the time he retired from the military. He lived another 30 years until 1858 when he died, aged 73.

Wallis is known to have been an amateur artist and in the past he had been credited with a range of paintings, including some scenes of Newcastle now more commonly attributed to the convict artist Joseph Lycett. McPhee, who is an expert on Lycett, said he had spent some time researching Wallis’s life in a bid to discover whether the military man had been a good enough artist to have produced any of the paintings credited to Lycett. That research that led him to discover Wallis’s manuscript describing his relationship with Burigon. As well as the manuscript, the album also contained a number of sketches from Wallis’s various postings around the world. These were of great historical interest, but not of conspicuous artistic merit, reinforcing Lycett’s claim to the Newcastle district scenes, Mr McPhee said.