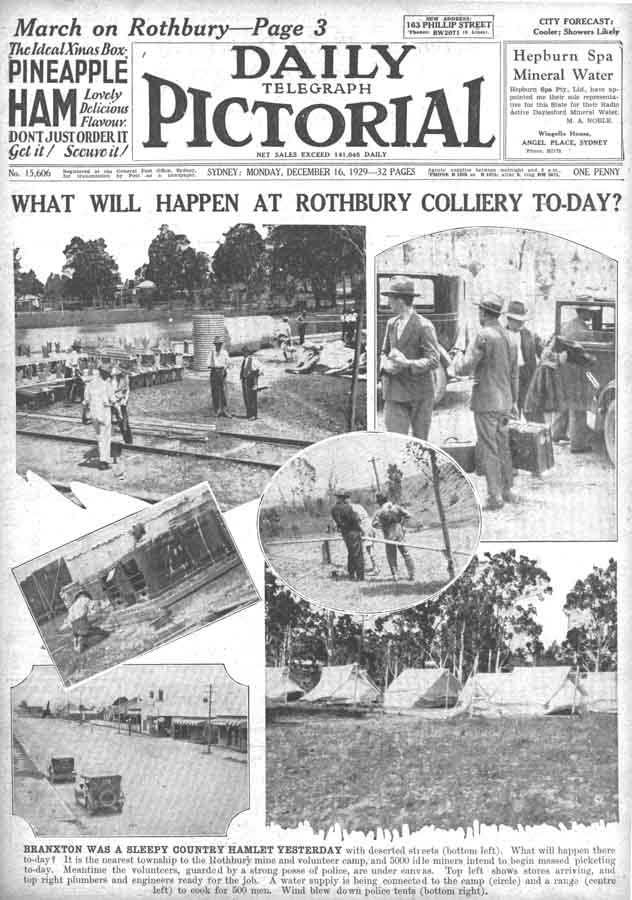

IT was December 16, 1929. Christmas was just around the corner, but it wasn’t shaping up to be a merry one for many residents of the Hunter Valley Coalfields of NSW.

In March, thousands of coalminers had been locked out of their workplaces by mine owners whose profits were being eroded by the steadily unfolding financial catastrophe of the Great Depression. The mine owners wanted the miners to take a hefty pay-cut, but the miners refused – unless and until the mine owners opened their books and revealed the true state of their profits and costs. With neither side willing to budge, the mine owners and their federal and state government allies saw the dispute as an opportunity to break the strength of the powerful miners union.

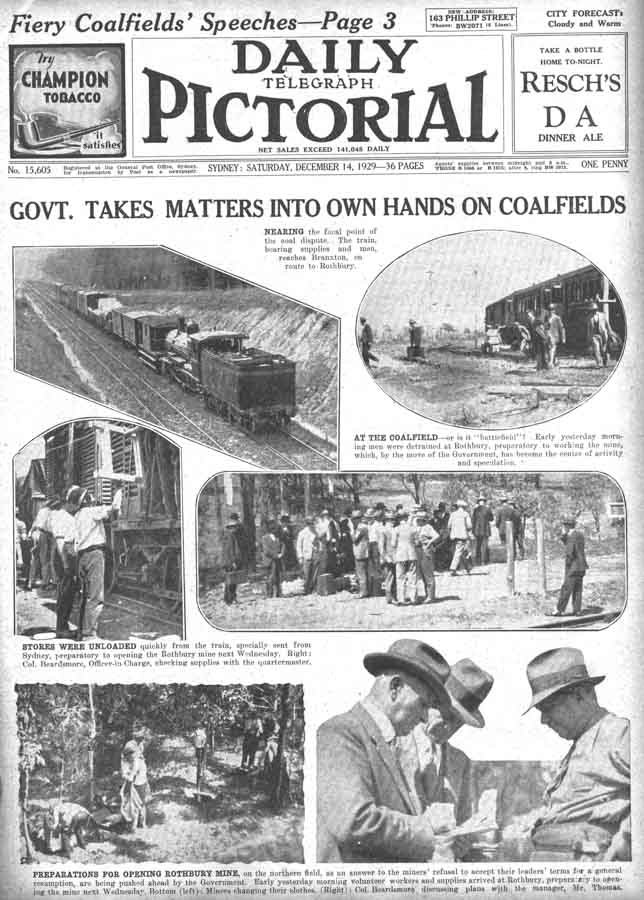

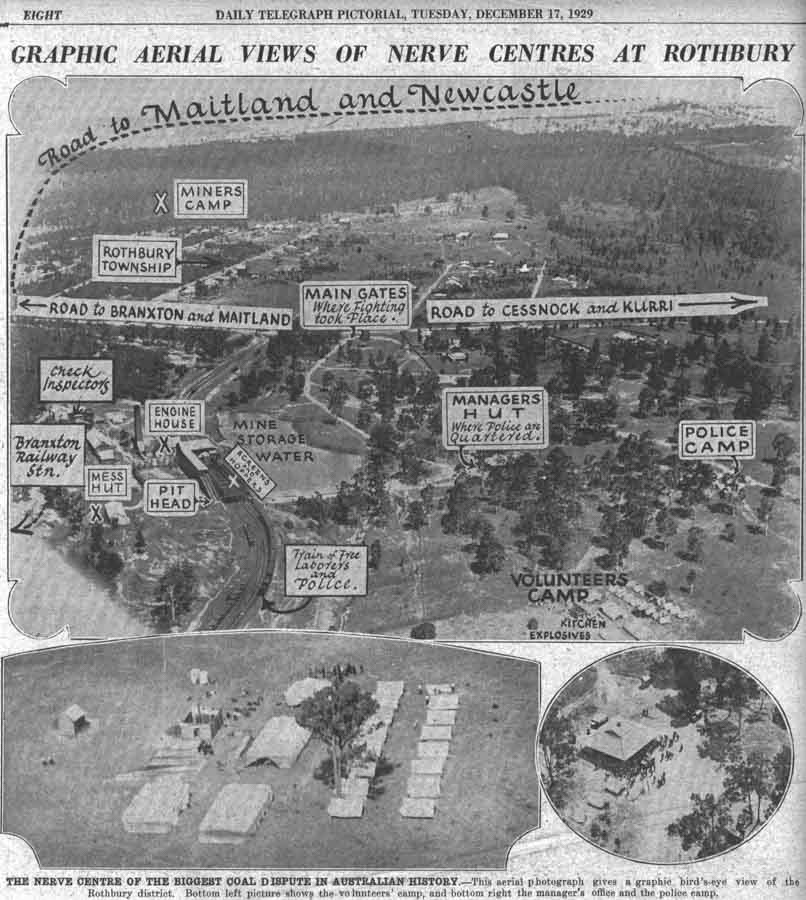

But by December the lockout had failed to starve the miners out as planned, so the mine owners and the NSW government called in “free labour” or “scabs” to run one of the mines – Rothbury – under police protection. The miners responded by resolving to set up a picket on the mine.

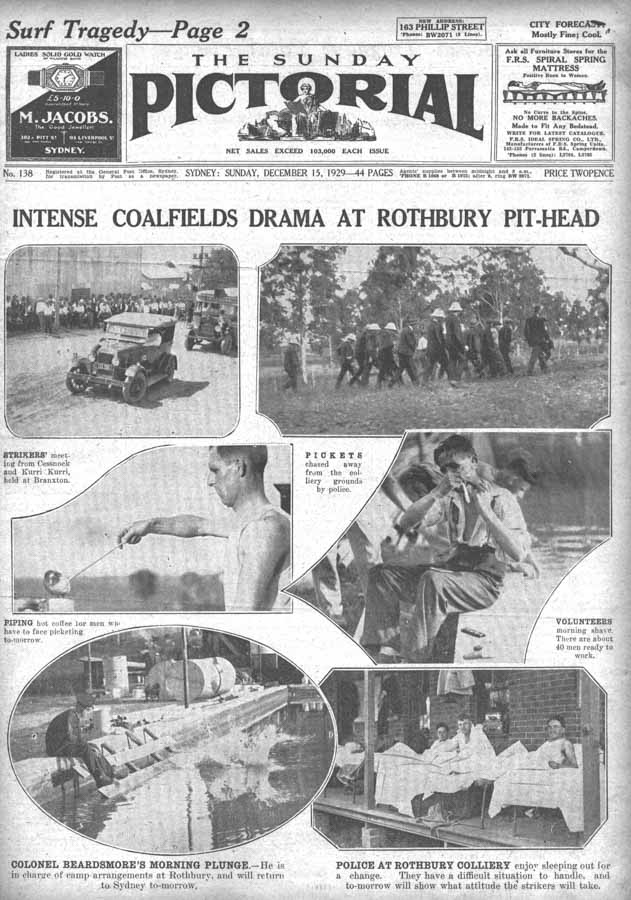

With little idea of the forces that had been set to oppose them, a mob of picketers and demonstrators went to Rothbury on that December day, determined to “speak to” the scab workers. The police were just as determined to prevent them, and they were armed.

The result was a chaotic shambles of ill-organised hostility that pitted rock-hurling miners against angry police with guns and batons. By the end of the riot the toll was one miner dead and several men wounded on both sides. The riot ushered in a brutal period of virtual martial law on the Coalfields, with squads of resentful police patrolling the towns and villages in trucks and cars, savagely enforcing the law against illegal public gatherings and subjecting union officials and “stirrers” to a sustained campaign of harassment.

After six more months of a lockout that should have been illegal under federal law because of the obviously collusive nature of its organisation, the miners were forced back to work on the owners’ terms, bloodied, bitter and harbouring resentments that would last for decades.

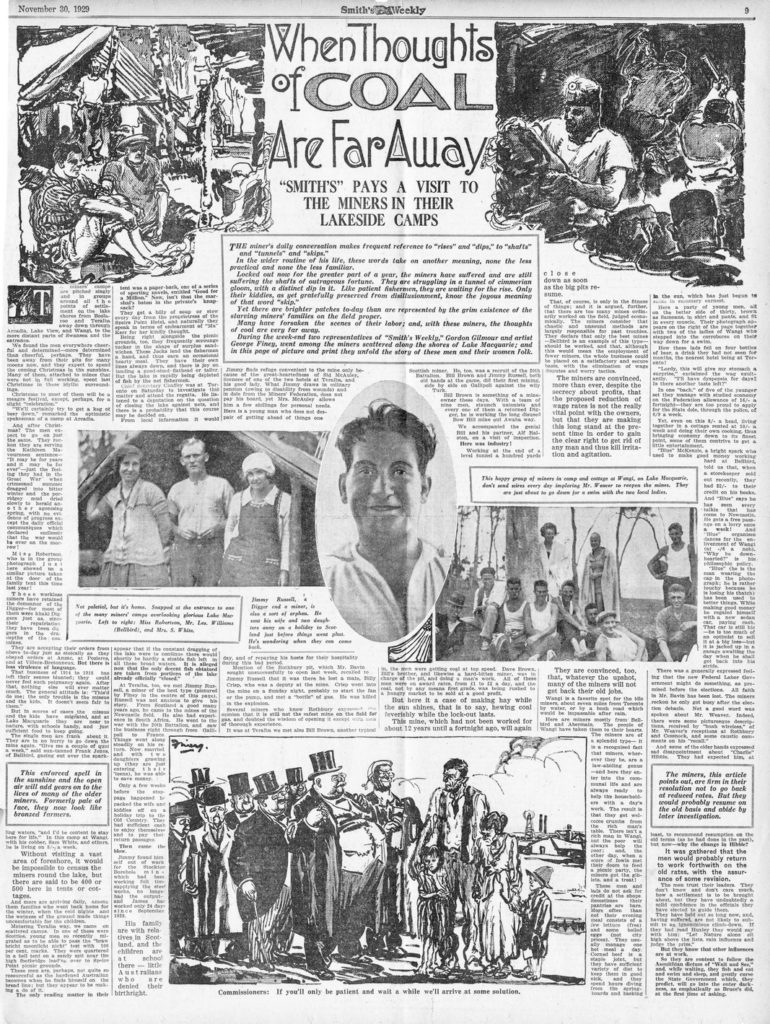

The great Lockout of miners in 1929

Many people have heard of the Rothbury Riot, but not so many realise its context. The brutal skirmish between striking coalminers and police was really the violent climax of a long, equally brutal industrial conflict still referred to in the Hunter as “The Lockout”.

In the 1920s, the mine owners on the Hunter coalfields were generally dominated by big commercial interests with investments not only in mining, but also in shipping and overseas trade. These powerful combines had enjoyed a long period of great prosperity, but when economic conditions turned against them, they looked to cost-cutting as the best way to shore up profits.

It was not apparent at the time that declining business conditions presaged the onset of the Great Depression, though in retrospect many clues can now be seen to have pointed that way. Coalmine owners in the United Kingdom, for example, had responded to falling profits by harshly forcing down the wages of their own workforce through their own lockout in 1926 – well before their Australian counterparts moved the same way. But by the time the Lockout began in the Hunter, it was already clear that the strategy had not helped bring profits back to the UK owners.

Political foot-soldiers and media mouthpieces

The mine owners’ approach typified a kind of reactionary employer radicalism that demanded total control over labour and was prepared to use its political foot-soldiers and media mouthpieces to win at almost any cost.

Many of the Hunter miners had come from the UK and retained powerful memories of bruising, no-holds-barred industrial warfare in their countries of origin to achieve even the most basic improvements in work conditions and pay. Transplanted to the different climate and social environment of Australia, they nurtured a highly democratic trade union model that permeated mining communities by providing and supporting varied social welfare functions. What employers and the state could not, or would not provide, the miners took it on themselves to create co-operatively.

Part of their ethos was a firm belief in taking no backward steps on pay and conditions. The ingrained distrust of employers meant there was little chance miners would entertain overtures from mine owners to share any portion of the burden of declining market conditions. Actually, under the employment models of the time they had no choice but to share that pain, since their shifts could be cut without notice.

Hence, when the mine owners began in 1927-1928 to intensify their always-latent demands for lower wage costs, the miners dug in, arguing instead for a wide-ranging inquiry into the coal industry that would examine the true position of mine owner profits. The mine owners made it clear that they would never permit their books to be opened. They also made it clear that they would use every mechanism at their disposal, including political leverage and blatant avoidance of industrial law, to have their way.

Hunter coalminers believed in the power of their union solidarity, but they were shown by actions elsewhere just how far the employers and their government allies were prepared to go to break that power. During the 1928 waterside workers strike for example – fought over similar issues to those emerging in the mines – the police fired on picketing workers, injuring four and killing one. The dead wharfie was Allan Whittaker, a veteran of the first Gallipoli landing in 1915.

The law was ignored to favour the mine owners

Amendments to industrial law in 1928 made it illegal for any organisation – employer or trade union alike – to “order, encourage, advise or incite” its members to “refuse to offer or accept employment”. Any organisation that did so “shall be guilty of doing something in the nature of a lock-out or a strike as the case may be”. There is no doubt that employer organisations in the coalmining sphere were breaching this law in the lead-up to the Hunter Lockout. How else could it be explained, for example, that every northern mine involved in the Lockout used identical words on their identically typed letters to their employees advising them that their services were no longer required? No such perfect uniformity had ever been seen before.

But the conservative prime minister, Stanley Bruce, ignored the clear evidence of illegality and did all he could to help the employers win. The federal attorney-general, Latham, actually commenced proceedings against one mine owner, the famous “Baron” John Brown, but Bruce ensured the action was withdrawn. Bruce and the Northern Collieries Association used every weapon they could, ducking and weaving to create the impression of being prepared to negotiate while actually striving to avoid any genuine attempts at resolution that did not involve the breaking of the mining unions.

The effects of the Lockout were quickly felt throughout the Hunter community. In the March, 1929 issue of the Commonwealth Bank staff journal, Bank Notes, the report from the Newcastle branch noted that: “any unrest whatsoever amongst the coalfields causes a serious depression in this city”. In May, Newcastle’s mayor, Harry Wheeler, tried to call a conference to head off the dispute, but his efforts were treated with contempt by the coal owners. At the time, the coal companies provided electricity to the Coalfields towns, and even this was used against the locked-out miners. Power to Kurri Kurri was cut off, but customers had to keep paying rental for their meters. Families scavenging for coal on waste ground were charged with stealing.

The state government, concerned that local police officers enjoyed too friendly a relationship with their communities on the Coalfields, sent police from other districts with instructions to be more harsh.

Ironically, the more people thrown out of work by the widening effects of the Lockout, the more expensive it became for the government to cover their food relief expenses.

Mining companies refused to open their books

From the start, the miners and unions demanded a royal commission into the coal industry. They believed that, if the mine owners were forced to honestly open their books, the alleged pre-eminence of the cost of labour would be exposed as a lie. The owners furiously opposed all attempts to have their books opened, and the few attempts to inquire into the true state of their trading figures were ill-informed, misled or both. When a royal commission was established, in June 1929, it quickly became apparent that it would never be allowed to study the books of the mine owners.

That battle was so comprehensively won by the mine-owning industrial combines that the miners lost faith in the royal commission almost from the start, realising their only hope for justice was the electoral defeat of the conservative Bruce government.

By October 1929, a large portion of the Australian public had become sickened by the government’s virulent anti-union, anti-worker bias. The growing depression was biting hard across the country, and when voters were given the chance to have their say on the weekend of October 12-13, they annihilated the government. Prime minister Bruce lost his seat, a feat matched only by his conservative compatriot and almost equally fervent anti-union campaigner, John Winston Howard, in 2007.

Elected was Labor’s Joseph Scullin, who had unambiguously promised to end the coal dispute, no doubt attracting much support by that means. Indeed, the mining union – hard-pressed as it was to support so many locked-out members on scant strike-pay – heavily backed Scullin’s election bid with funds. After the election the miners thought the royal commission was redundant. “Their” Labor government would re-open the mines as it had promised, they believed. This belief proved mistaken. The new government convened a fruitless conference between the parties that led nowhere.

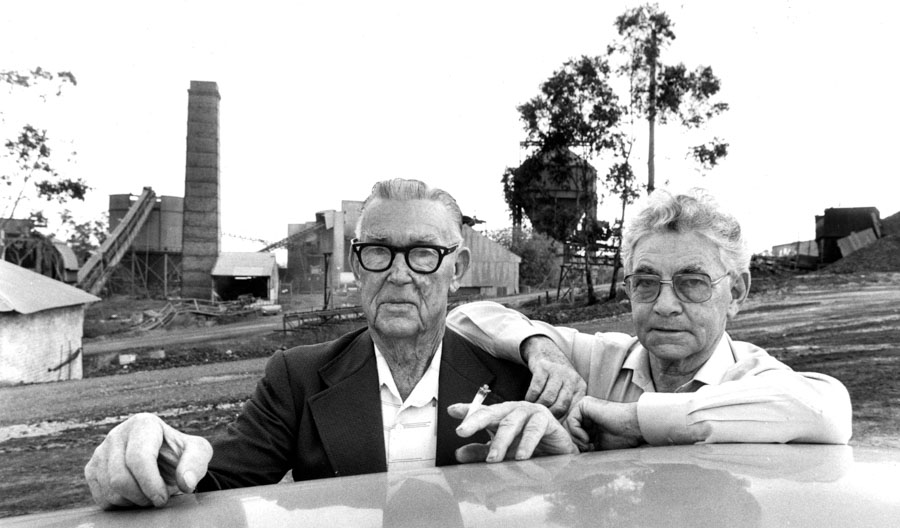

The Lockout was a deathly serious dispute whose course was intricate and riddled with political and industrial intrigue. Former union official Jim Comerford, who experienced both the Lockout and the riot, wrote the definitive book on the subject, Lockout, published in 2006 – shortly before his death. Even Comerford, who managed a laudable degree of dispassionate fairness in his detailed retrospective analysis, admitted the subject could occupy many volumes if every angle was pursued.

Labor Government breaks its promise to miners

By November 1929 it was plain that the Scullin Labor government would not honour its promises. Still, the mine owners – perhaps worried about what the change of government might mean to them – actually moderated their demands, scaling back their proposed pay-cut and dropping a number of union-busting claims.

In retrospect, Comerford wrote, the Lockout should probably have ended there. But bitter feelings were running too high and the compromise was not acceptable to angry miners or their communities.

At that point, where the Bruce conservative federal government had left off, the Bavin Coalition state government picked up. The NSW government announced that it would re-open four Hunter mines, by force if necessary. Soon the government’s attention settled on Rothbury colliery as the focus of its union-busting attention. And as the government moved to bring its “free” labour to work the mine, the angry miners – feeling betrayed and besieged on all sides – marched out to form their picket and demonstrate their frustration.

Why had no government enforced the clear-cut industrial laws that forbade collusion among unions or employers and declared the Lockout illegal? Why had the royal commission been so firmly excluded from studying the true finances of the mine owners? Why had the Scullin Labor government so comprehensively betrayed its unambiguous promises to the miners? And why now, did the Bavin NSW Coalition government decide to ratchet up its pressure and create a crisis point by overt provocation? These are the questions that nobody would answer. The only answer most miners and mining communities could see was that the money and connections of the wealthy and powerful mine owners trumped the cause of equity and trumped even the law itself.

The weather just before December 16, 1929 – the day the government declared it would re-open Rothbury with “free labour” – was hot. Jim Comerford was just 16 and he was more interested in swimming in the local waterholes than in industrial matters, but the Lockout was such a huge event that its influence was inescapable. In a 1988 interview with journalist Marjorie Biggins he recalled the knots of people on the streets of Kurri Kurri, all talking about the state government’s planned re-opening of Rothbury. A big meeting the night before was angry, and passed a resolution to march en masse to the colliery. Boys weren’t supposed to go, but Comerford and his mates saw it as an adventure not to be missed. He and his mates left their mothers crying at home and joined the miners.

At the same time, trains carrying the “free labour” from Sydney were on their way up the line. As the trains passed through stations, boys and men ran alongside and spat on the windows to register their disgust with the “scabs”.

Returned WW1 diggers led the march

A convoy of buses and trucks formed in Kurri Kurri to take the miners to Rothbury. Hundreds of women lined up to see the convoy off. A big tree – felled across the road to stop the vehicles – was quickly manhandled out of the way and the convoy made its way to Greta. The Kurri Kurri men camped in the park in the main street of Greta for the night, and in the distance they could see the bonfires of their comrades from Cessnock who had already arrived close to the contentious colliery. Returned servicemen who had fought in World War I were conspicuous among the groups at Greta, and they led the camp in a singalong. Few slept that night in anticipation of the next day’s confrontation.

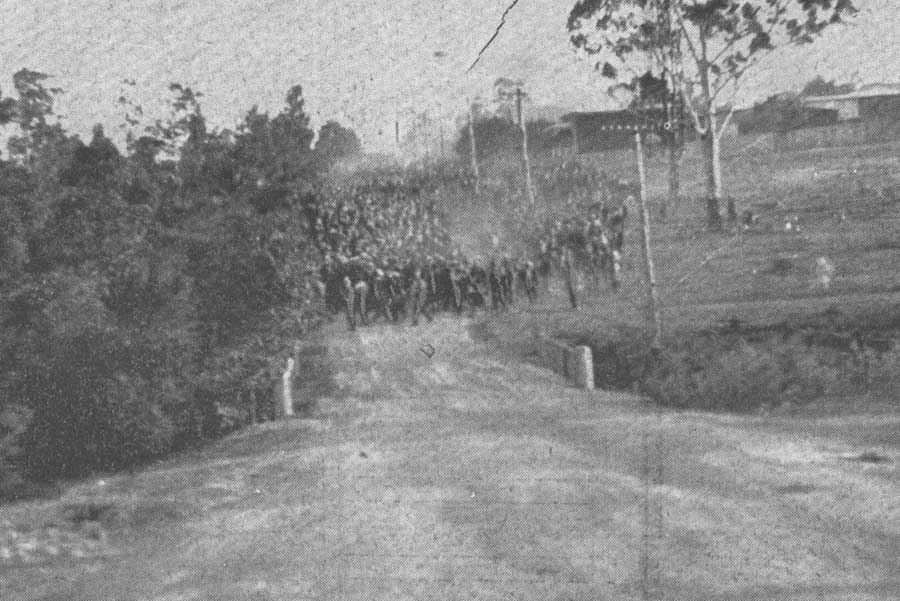

Just before dawn the miners’ pipe band started to play and a column of miners began to march from Greta to Branxton as the red rays of the sun shone through the surrounding trees. Everybody, even the band members, wore their pit clothes and Comerford said the mood was picnic-like. At Rothbury the column met up with the Cessnock men on a hill overlooking the colliery.

To Comerford’s surprise, and to the surprise of many others, there seemed to be little involvement or organisation by union leadership. This was a grass-roots demonstration. A local man addressed the assembled thousands of miners, telling them they had come a long way, and not for nothing. Their plan was to approach the “scabs” and persuade them of the error of their ways. The self-appointed leader – a Lancashire man named Sheridan – suggested the mob surround the pit to dilute the police defence, but the miners didn’t pay attention. Instead, they filed down the hill behind their pipe band, approaching the mine fence in a massed clump.

Visibly tense police

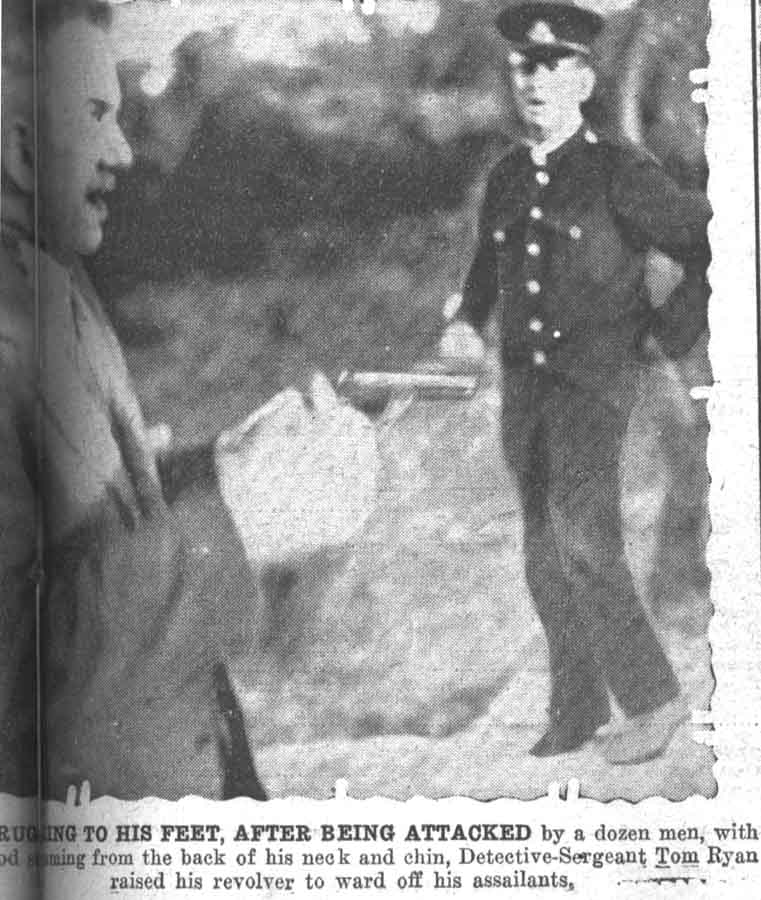

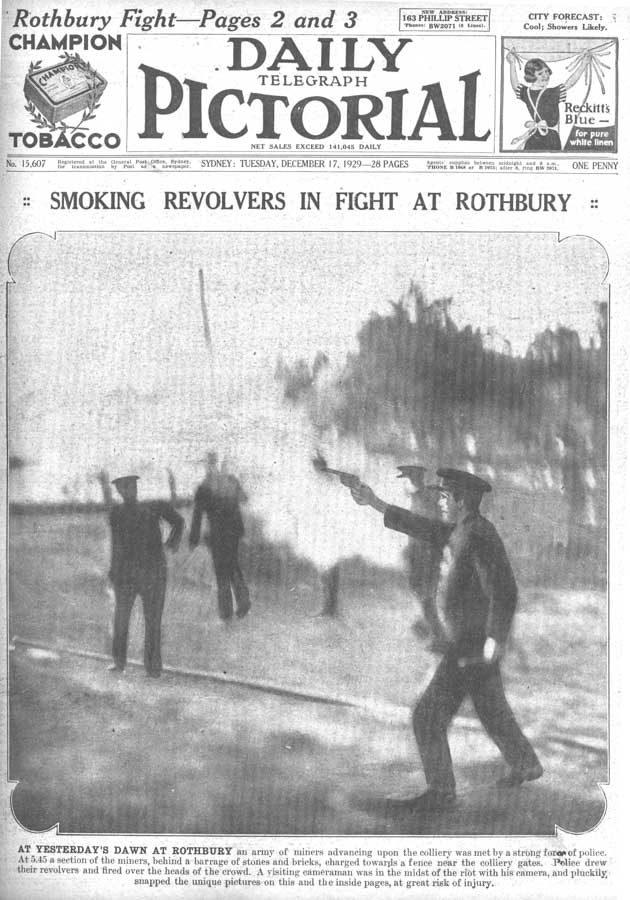

A visibly tense policeman met them at the colliery fence and warned them they would not be allowed to enter. The leaders ignored him and breached the fence. Then the riot began. At first police on foot with batons tried to stop the rush. When that failed, mounted police joined in but they couldn’t stem the tide either. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting between miners and police was all around.

The returned servicemen among the miners were infuriated when they saw the army tents that had been set up to house the “scabs” and some even recognised former comrades in arms among the ranks of the police. Some of the hatred and indignation was personal, from both sides.

Some miners pulled mounted police off their horses and that – according to Comerford in his 1988 interview – was when the shooting started. Panicked miners found it harder to get out than it had been to get in. Hemmed in by rows of empty coal wagons, their movement was restricted and they found it hard to get out of range of the police firearms. The police drove them back over the fence and an angry stand-off followed, with furious shouts and insults directed at the police, who nervously stood their ground, most with weapons drawn.

Miners ripping up rails

Away from the scene of first confrontation, another group of miners worked through the fence and started ripping up rails at the colliery siding. They were detected and chased by mounted police and, as they were escaping, some of the police on foot spotted them and began shooting again. This unnecessary shooting angered the whole body of miners even more, bringing feelings to boiling point.

The third, and worst, clash came when a car was seen moving towards the colliery and a rumour spread that it contained one of the hated state conservative politicians. The car was mobbed, its windscreen smashed, tyres slashed and its driver knocked unconscious. The police charged with batons, but when this failed they started shooting again.

The miners retreated once more, leaving their wounded lying on the ground until a relative lull enabled them to be retrieved.

While vigorous pro-government propaganda muddied the waters of media reporting of the riot, the official injury lists tell a story. Many miners hid their wounds and sought treatment secretly to avoid victimisation in future.

The death of Norman Brown

Apart from the acknowledged death of 26-year-old Norman Brown, shot in the stomach by police, nine other miners were acknowledged to have been hit by bullets. Brown was said to have been hit by the police bullet while he was sitting in a paddock with a group of mates. One miner, shot twice in the spine, never walked again. Young miner Wally Wood, 21-year-old wheeler from Richmond Main colliery, was shot in the throat.

Years later Wally Wood told journalist Norm Barney about the incident. “I’d leaned down to pick up a rock to throw and something picked me up and put me in the middle of the road, flat on my back,” he said.

Jim Comerford, then just 16, was present and witnessed the shooting. He said later that he was within touching distance of Wally Wood when he saw a policeman rise from behind a bush, steady his revolver on his arm, take aim and fire, before running back to the police compound.

While Wally Wood lay on the ground, making choking sounds, a passing motorist – Mr John Bootland of Rutherford – inadvertently drove into the riot area on his way to a family picnic. One of Mr Bootland’s children, Maisie Bradbury of Telarah, recalled what happened. “We were on our way to a picnic when Dad drove past the spot where a man had been shot. There were bricks and stones flying in all directions and I could hear gunfire,” she told Norm Barney. Mr Bootland told his terrified children to lie on the floor in the back of the car while he put the wounded miner on the front seat, stemming the blood with his wife’s scarf. He drove to Branxton where an ambulance took Wally Wood to Maitland Hospital.

Police claimed they “aimed at the ground”

Comerford remarked acidly many years later how extraordinary it was that the allegedly armed miners, allegedly aiming at police, managed to hit none, while so many bullets fired by police who were allegedly trying to miss, managed to find targets in flesh and bone.

The police later claimed they all aimed at the ground or into the air, and said the bullets that hit miners must have ricocheted. Most miners scoffed at this story.

The official list of police injuries (again very incomplete), included bruises and lacerations.

Media reports insisted that some of the miners had been armed and that they were first to open fire. The same reports insisted that the police followed their orders to aim high or into the ground.

Comerford remarked acidly many years later how extraordinary it was that the allegedly armed miners, allegedly aiming at police, managed to hit none, while so many bullets fired by police who were allegedly trying to miss, managed to find targets in flesh and bone.

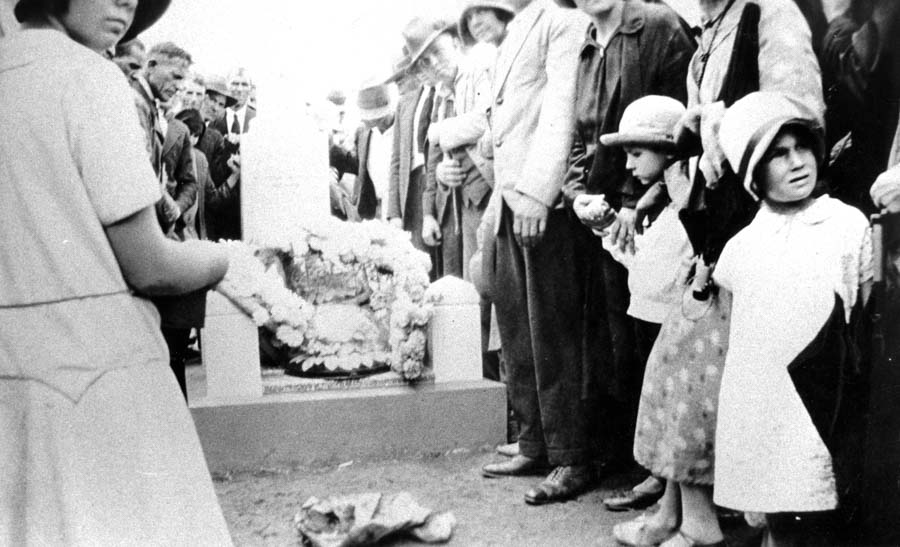

The miners left to lick their wounds, bury their dead and recuperate. Norman Brown was buried at Greta the day after the riot. Huge numbers attended the sombre, angry ceremony.

“What about Norman Brown now?”

The authorities, sensing victory, ratcheted up their pressure on the mining communities, unleashing the hated “basher gangs” of police in what amounted to a reign of terror in the Coalfields towns. Invoking “unlawful assembly” laws, the police broke up any groups of more than three people on the streets. Convoys of police vehicles patrolled the streets of Cessnock and Kurri Kurri, and mining union officials complained that their homes were invaded at all hours of the day and night by aggressive police claiming to be searching for incriminating evidence.

The Lockout continued for another six months, by which time the mine owners and their government allies had finally succeeded in starving out the miners and the mining communities.

In June 1930, when the discouraged miners voted to return to work with reduced pay, under terms dictated by the mine owners, tradition holds that, in the silence following the momentous vote, a lone voice loudly asked: “What about Norman Brown now?”.

Good article. My grandfather’s brother, Richard Thomas, was the manager of Rothbury at the time of the riot. His son, Keith Thomas (cousin of my father’s) was 12 years old at the time. I asked him some years ago (not long before his death) if he remembered anything of that day. He said that all he remembered was crowds of miners heading down the laneway beside the house (the manager’s house where the family lived somewhere at the mine). They were shouting and banging on the old paling fence with sticks as they went. Some men pulled loose palings off the fence as they passed. Keith’s mother and siblings were with him in the house. They all hid in the bedroom with the curtains drawn.