My mother was adopted, so our family tree is a bit complicated. On her side, the biological family branch was at a dead end for a long time, until a late-life DNA test by my mother unearthed some results.

On the adoptive side, though, it’s an interesting set of branches that I’ve recently started to follow. My main interest has been to establish the facts – if I can – about the Aboriginal heritage of my adoptive grandfather, Jack Pritchell. This has been talked about in our family for many years, but I’ve never been able to clarify the story.

With a few days intensive work on Trove and Ancestry, and bearing in mind some titbits of information gleaned over the years from various relatives, I’ve managed to narrow things down a lot. And in the process I’ve been introduced to some remarkable characters, of whom one of my favourites is my grandfather’s uncle, Tom Pritchell. Tom Pritchell was copiously memorialised by a 1930s newspaper correspondent who had worked with him as a stockman on a cattle station north of Gloucester, NSW, and the articles now digitized on Trove paint a vivid picture of extraordinary characters in an interesting place and time.

To set the scene, the documented story of the Pritchells in NSW begins with a pair of convicts.

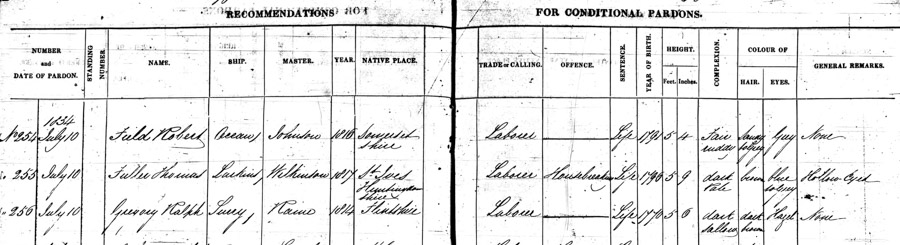

One, by the name of Robert Fields, was born around about 1790 in Milford Port, Somersetshire, England. He was sentenced to death in August 1815 for stealing silver plate, but the sentence was moderated to transportation for life. He came to New South Wales aboard the ship Ocean, arriving in January 1816. He was pardoned on July 10, 1834 and died on June 1, 1869, at Port Macquarie.

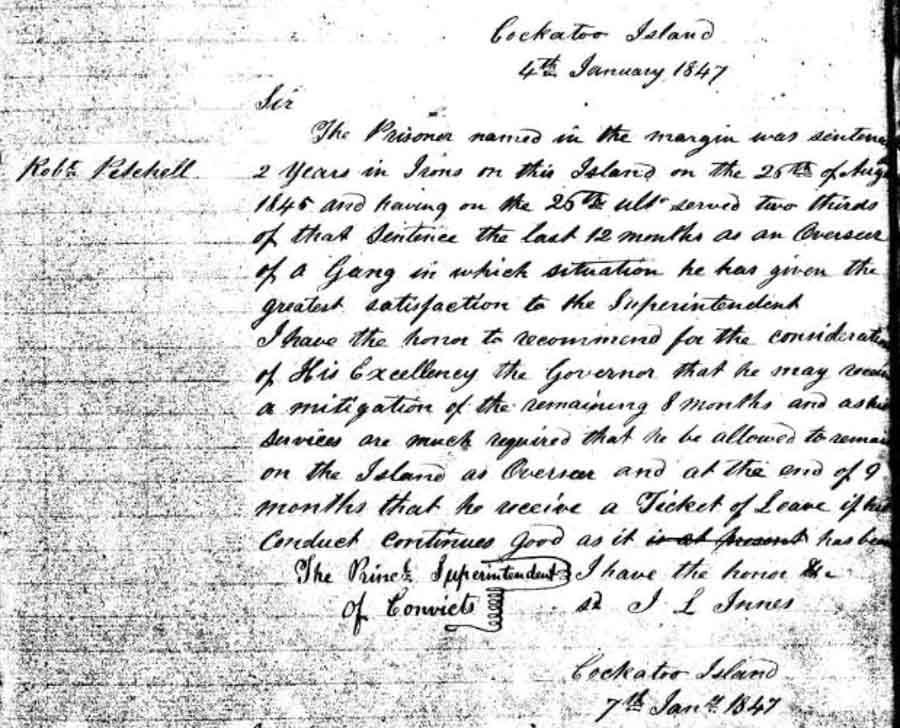

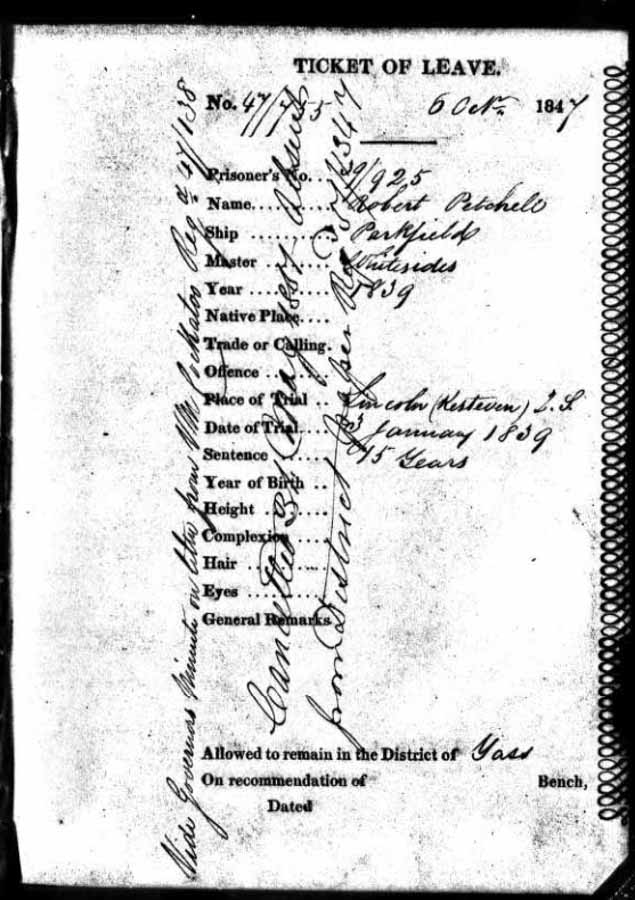

The other was Robert Pe(t)chell, born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1817, convicted of horse-theft on January 3, 1839 and transported to Australia on the convict ship Parkfield, departing on May 13, 1839.

According to convict records Fields was five feet four inches tall, had a ruddy complexion, sandy to grey hair and grey eyes. On May 11, 1825 he was sent to work at Port Stephens to work for the Australian Agricultural Company. He was listed as living there in the 1828 census.

At some point Fields appears to have been transferred by the AA Company to one of its inland cattle properties, probably Giro Station, north of Gloucester, NSW. There are no marriage records for him, but he fathered some children, including Mary Fields who was born in the Gloucester district on July 12, 1835.

It seems to me highly probable that the unidentified mother of Fields’ children was an Aboriginal woman – perhaps working at Giro Station too. I am guessing that their baby, Mary, was raised at Giro, which was one of a cluster of very large adjoining properties, on which was a big population of workers, including hundreds of Aboriginal people.

How our second convict Robert Pe(t)chell got to Giro I am not sure. In his convict records he is described as five feet, five and a half inches tall, of dark sallow and freckled complexion with brown hair and brown eyes. The records add this detail: “Eyebrows meeting. Man, woman, two half-moons, sun, seven dots, HPMPHRPBOP, heart pierced with two darts. T inside lower right arm, woman, cross pipes, heart, cross pierced with two darts, and mole on lower right arm”. He was clearly a well-tattooed young man when he arrived in New South Wales to serve his 15-year sentence. I am guessing the string of letters tattooed on his body may have been initials of family members.

It seems Pe(t)chell did not behave well at first, since on August 25, 1845, for repeated absconding, he was sentenced to two years in irons at Cockatoo Island. Two-thirds of the way through that sentence he was acting as an overseer of a convict gang and had pleased the principal superintendent enough to be recommended for a ticket of leave at the end of his sentence. His ticket of leave was granted on October 5, 1847, and it states that he was supposed to remain in the district of Yass.

Seven years later he was in the Gloucester district, probably at Giro, since on July 12, 1852, he is recorded as marrying Mary Fields, the daughter of Robert Fields. He would have been about 40 years of age at this time, and Mary would have been 16 or 17. The marriage is recorded as occurring either at Taree or “Manning River” – probably the Upper Manning at Giro. Neither bride nor groom could write, and each “signed” the certificate with their “mark”.

The couple had about 14 children. Quite a few are listed in records as being born at Manning River, Giro Flat, or Giro Station, so I presume the couple continued to live and work there for some years after their marriage. At some point they moved to Thalaba, on the Williams River near Dungog, where they lived the rest of their lives. Robert died there on August 8, 1901, and Mary followed on August 24, 1906. By that time, the family name had morphed into Pritchell, in which form it remains today.

When Mary died, the death certificate gave the cause of death as “exhaustion” and “cerebral haemorrhage”. In the column marked “mother” the document states “not known”. In that marked “Children of marriage” is written: “Thomas, 50; Lizzie, 45; Robert, 40; John, 35; Mary, 29; William, 27 – living”, and “eight females dead”. Of those children, it was Robert who sired my adoptive maternal grandfather, Jack.

For those using this article for their own family history purposes, Robert Pritchell Junior married Ada Harriett Williams at Dungog in 1900 (Ada had been born in 1869 at Stroud). Their children were Robert (1900 – 1901), Herbert Bruce (1901-1955), Jack Kenneth (1903-1973), twins Mary and Eric who were born and died in 1906, William Claude (1906-1968), Elsie May (1910-) and Cecil Thomas (1914-1985).

Stockman Tom Pritchell

But just at present I’m most interested in Tom Pritchell.

Quite a lot can be said about Tom Pritchell, thanks to articles by his old friend Richard Hinton, published in The Wingham Chronicle and the Dungog Chronicle in 1932. Richard Hinton had lived as a child with his parents on the sprawling cattle station known as Cooplacurripa, which adjoined Giro Station where Tom Pritchell was probably born. Hinton’s parents moved away to Nowendoc, but young Richard went back to Cooplacurripa to work as a roustabout, stockman and general hand. He was a good writer, and his extensive descriptions of people and events at the station during the late 1800s are colourful and compelling. The station, and other lands surrounding it, were owned or leased by the Mackay family – a powerful and wealthy force in the district at that time. It is said that, at its peak, Cooplacurripa covered a million acres and contained 13,000 cattle, many of them effectively wild in the rugged, mountainous country.

Stockmen at Cooplacurripa had to be excellent horsemen and bushmen. Tom Pritchell was clearly both. In his second long article on “Good old days on Cooplacurripa”, Hinton wrote that he would “first refer to three Aboriginal hands employed on Cooplacurripa about the year 1868”. The three men he described in that article were Old Billy Barlow, King Micky and Tom Pritchell. To quote excerpts from Hinton’s articles:

Tom Pritchell was on Cooplacurripa Station for years as a stockman. He died at Cooplacurripa, and his mortal remains rest not far from the home stead. Tom was a splendid horseman, and the same can be said of him so far as handling cattle was concerned. He was a fine man in the bush. Tom and I were head stockmen at Cooplacurripa in W. H. Mackay’s time.

I remember that when I first went to work on Cooplacurripa Station, we had to ‘point’ our own nails and shoe our own horses. We would have one day pointing nails, because not everyone could do it. Tom Pritchell and John Andrews were the best hands at this work. The next day we would shoe the horses. Sometimes we would have fourteen or fifteen horses to shoe before we could start out in the bush. This pointing and shoeing business used to take place every fortnight or three weeks. The day after shoeing, all hands would leave the station for various parts of the run.

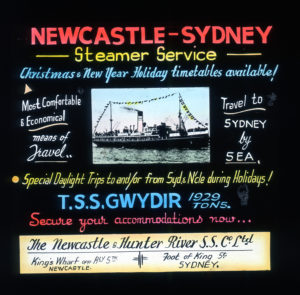

Sometimes Tom Pritchell and myself would have a day off, and we used to ride down to Wingham, where we usually had a pretty good time of it. In those, days Mrs. Brown kept a hotel where Reg. Platt’s business premises stand to-day. The hotels did not close those days till 11 o’clock at night. When Tom Pritchell and I started for home, we usually had a ‘life-saver’ in each pocket — and a couple on the saddle in front of us. We would ride straight through to Cooplacurripa, and very often started work straight away, after riding the best part of the night. But they were good times, those— and Tom Pritchell was one of the kindest and most generous hearted mates I ever had.

Tom goes on a wallaroo hunt

A much earlier article dealing with Tom Pritchell was published in The Manning River Times on May 20, 1899. The author isn’t named, but I’d be surprised if it wasn’t young Hinton:

A very amusing hunt after wallaroos took place a few weeks ago, by a small party, on the Upper Manning. It appears that at the back of Mr Sam Frost’s residence, at Tigrah Station, there is a mountain that is almost perpendicular on one side, with a ledge of rock overhanging the river. On the top of this mountain is the favourite haunt of the wallaroo. Unlike the kangaroo and wallaby— when hunted, instead of making for the scrub— the wallaroos invariably make for the extreme edge of a precipice, where they use their strong tail as a prop, and sit bolt upright; and when once they place themselves in that position, it is very hard to dislodge them, unless they are shot. However, on this occasion the hunters had only their dogs and horses to depend on.

Mr Elijah Frost, one of the hunters, knew well from experience that it would be useless under the circumstances to hunt them— unless he first cut them off from the precipice— which he to a certain extent succeeded in doing. However, in spite of his efforts, one old-man wallaroo — which seemed to have diverted the attention of three of the dogs, made for the edge of the cliff, and after propping himself there, stood upright; and as the dogs came up he successfully caught two, one after the other, in his arms, and toppled them over into the river below. The last dog managed to get a good hold of the wallaroo, and after doing a “Larry Foley’ for a few seconds, both went over together. By this time Mr Pritchell and Mr Frost decided to leave that spot, and wreak vengeance on all others that might come in contact with them that day, for the loss of their three dogs. They at once left in search of the other wallaroos that had made for the next ridge, and it was not long before another old man, about 4ft. 6in, was brought to bay; but he, being unable to get on to the edge of a precipice, scrambled up on a large solitary boulder, or rock, that was about 6 feet high, and there he sat and waited for the adversary — who was not long in coming up to him.

Pritchell, thinking that the position of the old warrior was an admirable one for dispatching him, spurred his horse up to him, and taking the butt end of his whip, did the ‘sledge-hammer’ business for a few minutes at him, but found that the old fellow was too well up in the art of self-defence to be hit so easily, and that all his strokes were a ‘wee’ bit short. However, Tom was not going to be done so easily as all that, so again driving his spurs into his fiery steed, he sent his horse up neck and neck with the wallaroo, at the same time raising the butt-end of his whip to make the final hit, expecting to crush him into a pulp, when the wallaroo quietly turned on the rock and caught the horse round the neck, into which it drove its teeth, when, before you could say ‘begob,’ the horse seemed to go mad, and away it bolted down the mountain side, doubled-banked this time— Pritchell on its back, and the wallaroo clinging to its neck.

Doubled up in a heap, insensible

After waiting on the top of the hill for a considerable time, Mr Frost, thinking that Pritchell must be having a high time of it somewhere, went in search of him, He was not long, however, before he got on his trail, and after following it for a considerable distance, found Pritchell doubled up in a heap insensible. A little further on lay the wallaroo quite dead, with one of its eyes torn clean out of its socket, and for a considerable distance further the ground was torn up, where the horse had evidently been doing a series of acrobatic performances. Only bits of saddlery were to be found, and the horse was not to be seen and has not up to the present time been heard of.

It was not long before Mr Pritchell regained consciousness, and after resting awhile, Messrs Pritchell and Frost wended their way towards home. They had not gone far along the edge of the mountain, when they heard the half -suffocated yell of one of their dogs in the creek below. Mr Frost at once mounted his horse and galloped post haste down to the creek — when he found his dog and a wallaroo fighting. The wallaroo seemed to have gained a partial victory over the dog, and was trying to put the dog’s head under water. Mr Frost at once dismounted, and taking his whip went into the water to down the marsupial. He had not advanced many steps into the creek before the wallaroo threw aside the dog, and made for him. Mr Frost immediately turned and ran for his horse, but the place being steep, and he having a light pair of elastic-side boots on, his headway was slow. Although he took the strides ‘ all right,’ still, as he said, every two feet he went forward he seemed to go four backward.

By this time the wallaroo had got so close that the cold shivers were beginning to do a handicap up and down the young man’s back, acquainting him by a process of telegraphy— that is only known to those that have been in a similar fix— that the hairy brute would soon embrace his legs, and leave the imprint of its teeth upon them. However, he was not destined to undergo such treatment, for just at that moment his dog came to the rescue, and seized the marsupial by the spine, and giving him a jerk, left it quite unable to fight again. The horse seeing the scuffle between the dog and wallaroo, and the frantic efforts of Mr Frost to reach him, made off, leaving him to walk five miles home with his disabled comrade, who was by this time stiff and sore. They managed to reach home about 9 pm, minus their dogs and horses, with only their bruises and haggard faces to show the extent of their pleasure in their day’s outing.

A grave by the river

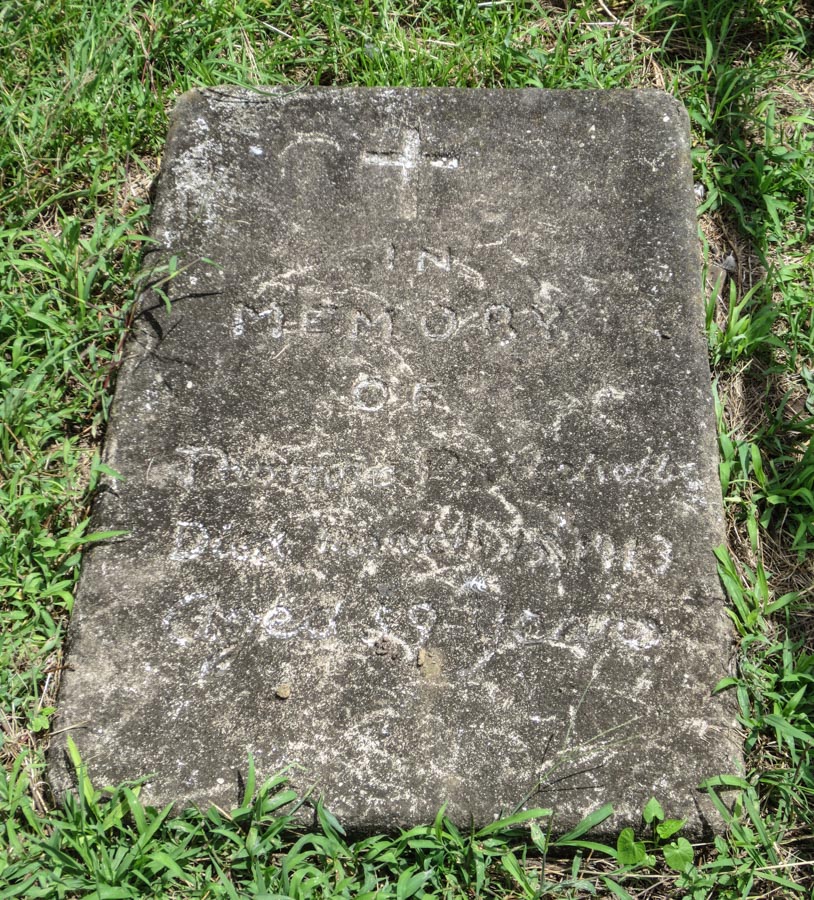

Tom Pritchell died at Cooplacurripa Station on March 15, 1913, aged 59. The Dungog Chronicle reported:

An old and respected resident of Cooplacurripa passed away rather suddenly on Friday night last, in the person of Mr T. Pritchell, a native of Dungog district where his relatives reside. On Thursday morning he had complained of a pain in his left side, but soon felt all right again, and on Friday he went about his work as usual in the best of spirits. He became ill again after tea, when everything that care and kindness could suggest was done for him. Towards midnight he felt better, and insisted on Mr G. Brewer, who was sitting up with him, retiring. On going into his room in the morning he found him dead, having passed away peacefully in his sleep. The interment took place on Sunday when, in the absence of a clergyman, Mr J. Frost read the burial service of the Church of England. The deceased was about 58 years of age, and had spent nearly all his life in the service of Mr J. K. Mackay, the last 23 or 24 years of which he resided at Cooplacurripa.

In 1924, in the Wingham Chronicle, writer F.A. Fitzpatrick described a rare motor trip from Wingham to Nowendoc, via Cooplacurripa. Paragraphs from that article follow:

The party pulled up at Cooplacurripa homestead, and Mrs Wilson, with that homely kindness so characteristic of her, invited the travellers to have lunch. Cooplacurripa homestead occupies an ideal site on the great run, with the waters of the river winding by, and ever crooning a song— a ‘rippling song’ that sounds louder and louder in the stillness of the night.

Down yonder, near the bank of the river, is a small enclosed plot, and there sleeps his last sleep one who was a faithful worker on Cooplacurripa. The cement stone on top of the grave bears the following inscription: — ‘In memory of Thomas Pritchell, Died March 15, 1913. Aged 59 years.’ It seems that Pritchell was a trusted employee on Cooplacurripa nearly all his life — having come there from the Dungog district.

On the station land, ‘neath a pleasing sky, now he sleeps; And the wind moans, loud as it wanders by. And it weeps: For a loyal spirit has taken flight; And the moon looks down on his tomb at night, and vigil keeps.

F.A. Fitzpatrick

I visited Cooplacurripa on February 17, 2021, and found Tom Pritchell’s grave still in place. The marker stone was very weathered but the inscription was still legible. Generations of owners had respected the grave, and someone at some time had even touched up the lettering with white paint. Station hand Peter Fitzgerald, who had spent many of his 59 years working at Cooplacurripa, said the grave had a picket fence around it when he first went to work there.

An interesting article about Cooplacurripa can be read here.

Richard Hinton’s first article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s second article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s third article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s fourth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s fifth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s sixth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s seventh article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s eighth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s ninth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s tenth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s eleventh article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s twelfth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s thirteenth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s fourteenth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Richard Hinton’s fifteenth article about “Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa” can be found here.

Thank you for writing such a beautiful piece on my uncle 4 generations back. I loved reading about his exploits as a cattle hand. My grandmother died when my mother was 3 years old and didn’t know much about her family. My sister and I (my loving sister has persevered at it longer than I) traced our ancestry back to the Pritchells . Our line is from Jemima, Tom’s sister.

Thanks so much Wendy. It’s lovely to get your feedback. Sincerely, Greg.

….Haven’t heard the name ‘Cooplacurripa’ for over 50 years …. wonder whether it was in stories of Jimmy Blacksmith or whether there was a connection to the ‘Mrs Wilson’ mentioned …. they first settled at Coolongolook before drifting up through Nowendock and onto the tablelands …. so many ‘rabbit holes’ so little time … but all immensely rewarding …

It’s a name to conjure with, that’s for sure.