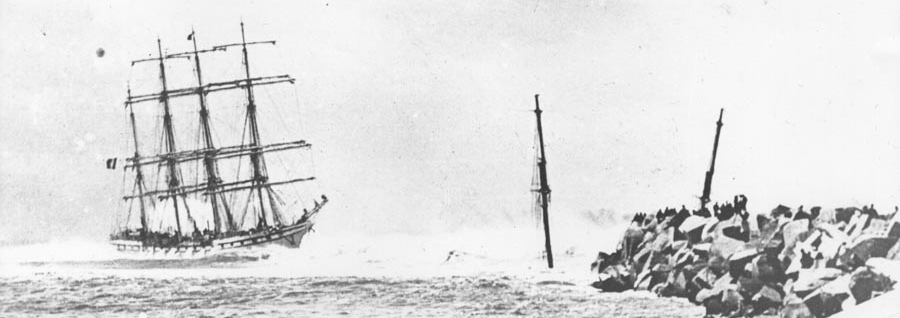

For well over a century, residents of the port city of Newcastle, NSW, have lived with the wreck of the French barque Adolphe, lost on September 30, 1904. The remains of the once-proud steel four-masted ship have been steadily rusting away over the decades, and the ruined bow – which now forms part of the northern breakwater at the harbour’s entrance – is still an appealing subject for weekend photographers.

The story of the famous wreck has been written many times. One of the most comprehensive accounts I have seen is this detailed article by Ken Dutton (reproduced here with Ken’s kind permission).

Adolphe was quite a new ship when it made its fatal visit to Newcastle, having been launched in March 1902. It left Antwerp on July 7, 1904, under charter to Newcastle mining magnates J. and A. Brown to load coal for Chile. Fatefully, it seems that the ship’s instructions were changed shortly after it left. Instead of going to Newcastle for coal, the orders were now to go to Sydney – a little further south from Newcastle on the NSW coast – for a cargo of wheat. Unfortunately the captain of the Adolphe did not receive these new instructions and headed for Newcastle as originally planned. The Adolphe actually passed Sydney Heads on September 28, and might easily have entered that very safe port with little trouble. But as far as Captain Joseph Layec knew, he was meant to go to Newcastle for coal, and that is what he tried to do.

Adolphe was off Newcastle on September 29, standing off the shore in rough seas and waiting for the tugs of the chartering company to shepherd it into port. Brown’s tugs didn’t turn up, however, no doubt because they were no longer expecting the ship at Newcastle. The tugs of rival firm J. Fenwick & Co went out to the Adolphe but Captain Layec preferred to wait a little longer for Browns. When the charterer’s tugs simply failed to appear, the captain finally accepted the Fenwicks tow on the morning of September 30. He was assured it was safe to enter the port, which had a reputation for being tricky and dangerous in the wrong weather. Two tugs, the Hero and the Victoria, took the ship in tow and, with no sails set and the local pilot in charge aboard Adolphe, they headed for the harbour entrance. Just as they were entering, a flag signal was flown from Nobbys Headland at the harbour mouth, telling the Adolphe of its new orders to go to Sydney instead of Newcastle. By the time the signal was near enough to be read it was too late.

With no choice but to keep going into Newcastle through its narrow and tricky entrance, the tugs and ship were hit by three freak waves that snapped the towline between the Adolphe and the Victoria. This was a disaster with no remedy. The lone remaining tug was powerless to fight the push of the waves and the ship was driven quickly onto the notorious “Oyster Bank” on the northern side of the harbour entrance. The Oyster Bank was already littered with previous wrecks and the Adolphe was reportedly smashed bodily down onto one of these, the ruined remains of the steamer Colonist. Another wave threw the ship into its final resting place atop two other wrecks, those of the steamers Lindus and Wendouree.

The heroic rescue of the crew by the Newcastle lifeboat Victoria is part of local lore. It was an extraordinarily brave and completely successful effort, earning the deep gratitude of the captain and crew, the ship’s owners and the French Government, which presented the lifeboat crew a purse of 30 gold sovereigns.

The wreck remained where it sat, since salvage attempts proved impossible. Over time the Stockton breakwater was extended and built over the top of the Adolphe and the other wrecks. This made it possible for brave and foolhardy people to climb the ship’s masts and rigging. According to maritime historian Terry Callen’s 1986 book, Bar Dangerous, “She was stripped of her spars. Her mizzen and jigger masts had fallen in a gale in 1905, and in 1908 the stern half was blown up. The two remaining masts were cut off and the stumps driven down. The fallen masts can still be seen today”.

In the 1980s it was still possible to clamber over the wreck, but repeated complaints about the risk to those who dared to do so led to it being fenced off. A viewing platform was provided, and the wreck of the Adolphe now forms the centrepiece of the so-called “Shipwreck Walk” along Stockton Breakwater.

Greg.

First Blog …the Adolphe.

I got interested by the colour of the hull as my Grandfather was the captain of a similar vessel and took her 12 times around the Cap Horn.

A little research …

The Adolphe was built in 1902 in Dunkirk. It was part of the fleet of the companie AD Bordes which employed most of the male of my family who lived in Dunkirk. It was named after Bordes eldest son Adolphe.

My Grandmother was a Van de Sande, family which came down from Jean Bart, privateer under Louis XIV creating havoc with the fleet of the VOC returning via the Channel….

That’s fascinating Eric. You’ll have to come and visit Adolphe one day!