If you ask most older Newcastle people where they were on the night the Norwegian bulk carrier Sygna went aground on Stockton Beach, they’ll probably be able to tell you.

Since European settlement in Newcastle there have been three really big hurricanes that have left lasting impressions on those who experienced them. All three of these giant storms are known to many by the names of the ships they destroyed.

The first was the Cawarra Gale, which lashed the NSW coast for days in 1866 and claimed dozens of lives – most of them on the SS Cawarra, which sank while trying to enter Newcastle Harbour during the savage storm. The next, on May 26, 1974, tossed a big Norwegian bulk carrier onto Stockton Beach, leaving much of the rusting hulk to rot there for decades, and went down in popular history as “the Sygna storm”. The third is the Pasha Bulker storm of 2007.

The Sygna storm was a once-in-a-lifetime reminder of nature’s awesome power. During its 150-minute peak the gale, with gusts of up to 172 km/h, buffeted the whole region and caused incredible damage.

At Terrigal, a 19-year old man drowned when huge waves smashed across a camping ground and hurled the car in which he was sitting into the ocean. A newly finished house in Francis St, Swansea, literally disappeared at the height of the storm. Pieces of the building and its foundations were later found more than a kilometre away. Another house, at Brightwaters, was lifted and removed from around its startled occupant who was left unharmed to contemplate his property’s brick foundations.

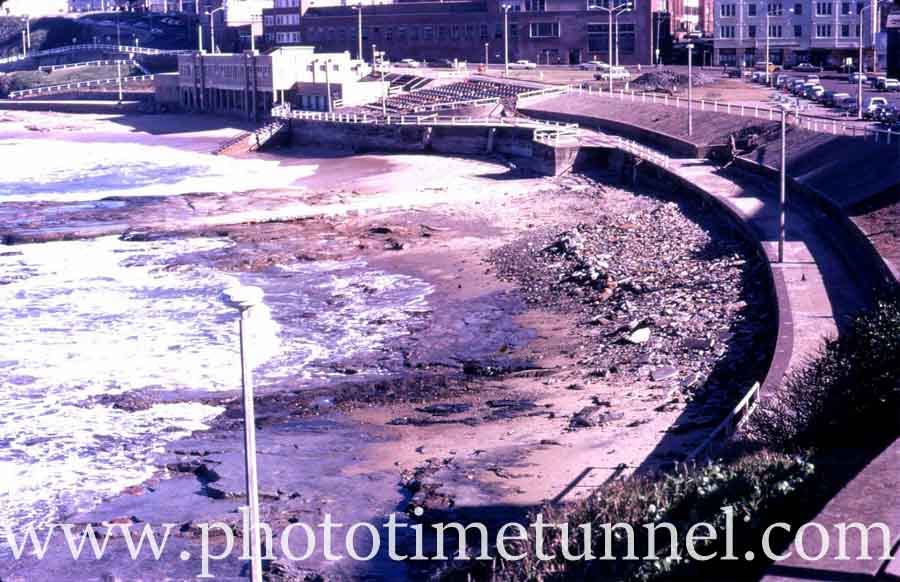

Some other homes either disintegrated or were so badly damaged they had to be demolished in the following days. One Swansea home was destroyed by a fire that broke out during the storm, probably as a result of an electrical fault. A timber church at Morisset was shifted more than 6m from its foundations and at Catherine Hill Bay half of a 200m jetty was destroyed. The Stockton ferry wharf was partly demolished and pieces washed up in Newcastle Harbour. Police estimated that 200 cars were wrecked or damaged. One was washed off Nobbys breakwater and crushed against a rock wall. Several motorists were injured in collisions as they tried to drive during the hurricane.

Houses lost their roofs

People cowered in their homes as countless television aerials crashed down on rooftops and windows were smashed. Hundreds of blacked-out houses lost their roofs and live wires whipped and sparked in the screaming sky. Trees splintered and fell. Caravans flew like kites, with one blowing more than 60m from its site.

For those on the water the fear was greatest. Lives were lost at sea as yachts were crippled and sunk by the buffeting waves and howling wind. In the lakes and bays yachts and cruisers snapped their moorings and were broken up on rocks or dumped in the yards of waterfront homes. One was found next day halfway up a tree. At Wamberal and Avoca waves crashed their way into beachfront houses, cascading through rooms and forcing residents to flee.

When daylight finally dawned residents were greeted by the sight of streets littered with tree limbs, pieces of houses, broken wires, stray shop awnings and broken glass. The cleanup, hampered by continuing rain and bad weather, took weeks. That’s the piece of weather that those who saw it will never forget.

But for all that, the hurricane is always known as “the Sygna storm”.

While most people gritted their teeth by torchlight in the battered suburbs, praying their walls and roof would hold together, there was a heartstopping drama unfolding in the busy port of Newcastle. And just offshore a giant steel ship was fighting a grim and losing battle with the sea.

The Sygna was just one of many ships waiting off Newcastle when the storm struck. There had been a surge in demand for coal and the port couldn’t keep up with the loading schedule. The seven-year-old, 53,000 tonne Norwegian freighter had arrived off Newcastle from Japan five days earlier and was waiting to load a cargo of 50,000 tonnes of Hunter Valley coal, destined for European customers.

Sygna missed the gale warning

In the middle of the afternoon of May 25, the Sygna’s skipper, 57-year-old Ingolf Lunde, missed hearing the NSW Weather Bureau’s gale warning for waters south of Kempsey. Later, when he watched the TV weather report and saw the warning of 40-knot winds, he wasn’t unduly perturbed. Winds of that speed were not unusual, he thought, and his ship could ride them out without too much trouble. Anyway, strong wind warnings had been broadcast over the previous few days and to Captain Lunde it may have all been starting to sound routine.

Until about 8pm the biggest wind gust had been 35 knots, but after 8.15 things got markedly worse. The wind swung around to the south-south-east and started gusting up to 50 knots. The Sygna dragged its anchor at about 9.30, but Captain Lunde wasn’t inclined to fret even then. He had the cable recovered, set a watch for the night and went below to sleep.

By 11pm the weather-watchers at Newcastle’s Nobbys signal station were getting very apprehensive and they warned the ships at anchor off the city that the storm was likely to get worse. Most of the ships took the hint, and by about midnight only three ships remained. The little Chinese-owned ship Cherry couldn’t raise its anchors because the cables were tangled, and the Norwegian bulk carrier Rudolf Olsen was determined to stay put because it didn’t want to lose its position as next in line for coal loading.

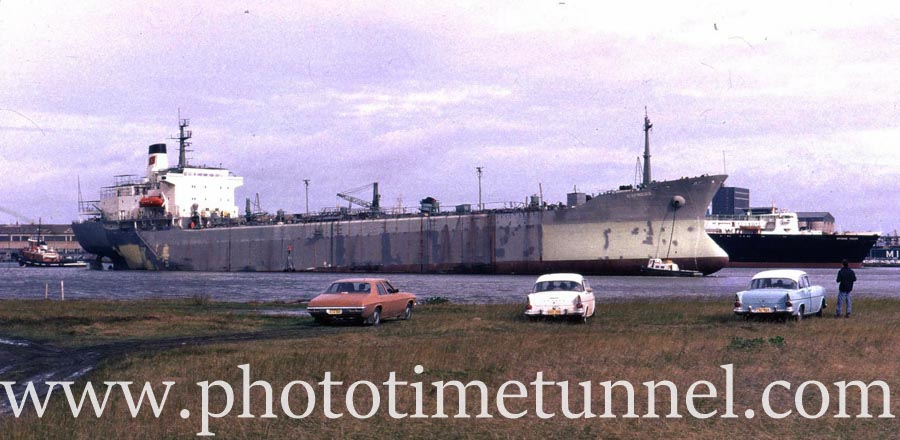

At midnight the winds died down a little: the calm before the storm. A quarter of an hour later, all hell broke loose, and so did six ships moored in Newcastle Harbour. The harbour pilots and tug crews who had been expecting a quiet night suddenly found themselves in the middle of a chaos of confusion. Winds of up to 70 knots were screaming across the water, snapping giant cables and sending huge ships careering around the harbour. No sooner was one secured than another was loose. Ian Wright of BHP Shipping described how he had taken command of the Iron Baron on Thursday, May 23. “The following day we moved to what turned out to be the safest berth in the port – the floating dock. During the blow our biggest worry was that the dock would move, breaking the power cables to the shore. Without the dock’s pumps it would have sunk, taking us with it as we had plates off the hull. A mate of mine was master of the Iron Flinders, which was also berthed in the Steelworks channel: she managed to hang onto the wharf by one single forward tension wire.”

One ship, the Brisbane Trader, was among a group that had broken loose in the Steelworks Channel and it was lying right across the path of the drifting, engineless tanker Express, just built at the State Dockyard and being fitted out. The Express had already been re-secured once that night and had broken free again. Now it had to be pushed onto a mudbank to keep it out of danger. Another ship, the Man Lloyd, was tied up at Lee Wharf when all 18 of its cables parted (each was brand new polypropylene, 18cm in circumference), and it went drifting into the crowded confusion of the harbour.

Some time around 2am the surging waters of the port snapped the communication cables that kept Nobbys signal station in touch with Sydney. The port was left with nothing more than a low-powered domestic radio link. Shortly afterwards, the skipper of one of the harbour boats reported receiving a weak SOS signal. It was the Sygna, reporting itself aground and requesting two tugs to assist it. It was an impossibly optimistic request, given the hectic work to be done inside the port (where the surge was so powerful even the tugs struggled to make headway). The chances of a tug getting safely over the bar in those conditions were so remote as to be negligible. All Nobbys could do was to ask the sea-going tug Warrawee, based at Sydney, to standby in case it was needed.

The other two ships remaining close to shore were fighting for their lives. The Cherry, with its anchor cables still tangled, turned head to the wind and ran its engines flat out to keep its anchors from dragging. Its frightened crew didn’t get the cables untangled until conditions improved after 8am, when the ship fled, belatedly, to the safety of the open sea. The Rudolf Olsen, which had been reluctant to risk losing its turn at the coal loader, almost finished up ashore. The ship was luckily able to raise just enough engine power to turn its bow into the storm and hold on through the ordeal.

The captain was asleep

Not so lucky was the bigger Sygna. Although a Norwegian inquiry exonerated the ship’s officers from blame, there seems little doubt they’d have saved their ship if they’d turned and run to sea between 11pm and midnight when most of the others did. But at 11pm Captain Lunde was asleep. He had been so unconcerned, even by the 10pm gale warning he heard or the dragging of the anchor in the storm’s early stages, that he didn’t even bother dropping the ship’s second anchor. He went to bed and told his officer of the watch to wake him up if the anchor dragged again.

So, as the other ships around it left the area, the Sygna just sat tight, swinging at its single anchor while the wind and sea rose around it. By 1am the anchor let go and the ship was adrift. Captain Lunde, wide awake now, gave orders to weigh the anchor, but the weather conditions were so bad even this simple job became a major problem. By now the winds were gusting at 80mph. The captain ordered full speed ahead and full port rudder, finally deciding to head for the open sea. Too late.

Full of ballast water and drawing about 9m, Sygna was pushed sideways by the storm, bobbing up and down on the angry swell like a cork in a tub. The ship bounced on the bottom of Stockton Bight at least twice before it was pushed ashore and many believe it was one of these knocks that put the main engines out of action. Unable to turn the ship’s flailing head to the wind, Captain Lunde gave orders for a full starboard turn. A few minutes later, at 2.15am, Sygna was aground on Stockton Beach.

The crew of 28 men and two women – mostly from the Bergen district in Norway – were not in immediate danger. Captain Lunde had already made some contact with the Newcastle pilot cutter and he also sent a telegraph message to his shipping agents in Newcastle. He wanted help to tow his ship, which he was not yet ready to abandon. The harbour authorities planned to wait for daylight to assess the Sygna’s plight. They had plenty on their plate already and there had been no call for a rescue of the crew.

Red distress flare fired

After 4am the Sygna fired a red distress flare which was seen at Nobbys and helped locate the stricken ship. Captain Lunde again requested tugs at 5am, but was told the bar was too dangerous for tugs to leave port. As soon as daylight appeared, Newcastle Water Police took a four-wheel-drive along Stockton Beach to where the ship was stranded. They reported it was hard aground, but the crew appeared to be in no danger.

This assessment changed at 7.30am when the police reported that the ship now appeared to have broken its back and might be starting to disintegrate. Oil was pouring from the ship and a crack had appeared in its side. With news of the fractured hull, the Sydney-based sea-going tug – more than 5 hours away – was taken off standby. Williamtown RAAF was put on alert. The base agreed to supply a helicopter to evacuate the crew if requested.

But first an attempt was made to remove the crew by lifeboat. Police fired a rocket line aboard the ship and the famous photograph was taken of spectators and volunteers, rugged up on the rainy beach, hauling the line taut. The lifeboat attempt failed, however. The boat’s motor failed, the current was too strong and the danger was deemed too great.

By midday a helicopter was taking off from Williamtown and by 3pm the crew had been safely removed.

Captain Lunde, infinitely more worried about his ship now it was hard aground and doomed than he had been when it was lying alone on a single anchor between a gale and a hostile coastline, refused at first to leave. He had to be reassured that his departure would not cost the Sygna’s owners their salvage rights.

CONTINUED: CLICK NEXT PAGE TO KEEP READING

Greg,

I enjoyed reading the above account of the “Sygna” night. I had taken command of the “Iron Baron” (3) on Thursday, 23 May, 1974 & the following day we moved to what turned out to be the safest berth in the port, the floating dock. During the blow our biggest worry was that the dock would move, breaking the power cables to the shore, without the dock’s pumps it would have sunk, taking us with it as we had plates off the hull. Some of my cadets & junior officers were in that photo of the volunteers manning the rocket line. A mate of mine was Master of the “Iron Flinders” which was also berthed in the Steelworks channel; she managed to hang onto the wharf by one single forward tension wire. The “Express” was a new ship, built at the Dockyard, being fitted out.

Th