Anzac Day is nearly here again. The time when Australia’s politicians grab their flags and put on their sombre faces to prove that they are true patriots who love their country and support the men and women who have worn the uniform and put their lives on the line for the government and the nation over the past century.

Many of those politicians, I am sorry to say, are hypocrites. They are hypocrites because their actions don’t match their words. They weasel on about supporting the troops, but their support is sunny day support that melts as soon as the going gets tough. They send people off to stupid and wrong wars, then fail to support them when they come back scarred and damaged. When ex-service people need help they duck and dodge to avoid responsibility and cost.

One of the most glaring examples of this hypocrisy is the Morrison Government’s staunch opposition to a Royal Commission into veteran suicides in Australia.

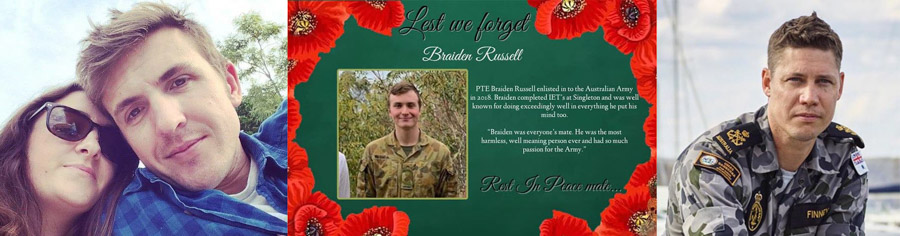

There have been at least 500 veteran suicides since Australia’s involvement in Afghanistan began in 2001. There were at least nine veteran suicides in Australia last October and November alone and at least another two in December. At least 13 more have occurred this year. The suicide rate among men aged 18 to 24 who have been discharged from the military on medical grounds is four times as high as that among members of the general public in the same age group.

Royal Commission

The causes aren’t well-understood, and that’s one thing a Royal Commission might help with. It is known for sure that many people in the military suffer post traumatic stress disorder. It’s also known that many have trouble readjusting to civilian life once they leave the military. It has often been reported that some elements of military leadership tolerate or ignore practices and behaviours – bullying, hazing, sexual assaults – that leave lasting scars. There have been serious questions raised over the allegedly unethical and gung ho culture in some units, with particularly disturbing allegations coming from the Brereton Report into the behaviour of some serving units in Afghanistan.

A major problem is the perception that the Government doesn’t want to know about potentially expensive medical claims from serving and former military personnel and that it drags its feet when it comes to providing help when it’s needed. Last year, for example, a Victorian coroner recommended an audit of the Department of Veterans Affairs when a veteran of service in Afghanistan suicided just weeks after the department rejected his impairment claim.

For the Government’s part, it has tried desperately to avoid a Royal Commission and, even after Federal Parliament voted this year in favour of a Royal Commission, it is still refusing to make it happen. Prime Minister Scott Morrison – having been dragged against his will to the point where he no longer declares himself against an inquiry – seems to believe that the Government has already done enough.

More than 400,000 Australians have signed a petition supporting the Royal Commission, prompting Liberal Senator Jim Molan (himself a former Army Major General) to mock those supporters as “ignorant” and the idea of the Royal Commission as “motherhood” and “apple pie”. (Senator Molan has, since those comments, sadly been diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer.)

The Government has established a National Commissioner for Defence and Veterans Suicide Prevention, appointing lawyer and former military staffer Dr Bernadette Boss to the role on an interim basis. According to her terms of reference, her office is to “predominantly focus on deaths by suicide among ADF members and veterans who have had one day or more of service since 1 January 2001, where the death occurred between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2018, as this is the period for which the most comprehensive and robust data and information is available. However, the National Commissioner will be able to include other cases as they consider appropriate”.

Some in the veterans community, however, fear that the office of the commissioner may ultimately become just another cog in the same machine that now seems to work so hard to deny and delay veteran claims, and which is alleged at times to cover up evidence that reflects poorly on the defence forces and the government. This may be an unfair belief, but is perhaps not surprising under the circumstances.

The belief of those who support a Royal Commission is that it will be able to demonstrate greater independence from the Government and defence forces, and will be able to ask hard questions without fear of repercussions. Given the Government’s proven practice of penalising with savage budget cuts any government organisations that dare to offer any criticism of its policies and practices, and its equally demonstrated love of stacking departments and tribunals with its own partisan hacks, it is no surprise that many people want an inquiry that is shielded from these standard government tactics.

I would suggest that the Government and the defence forces don’t want an independent inquiry that might show them in a bad light. And I would suggest that any independent inquiry would almost certainly do exactly that.

History of neglect

Australian governments have a history of abandoning and neglecting veterans that goes back as far as the end of The Great War in 1919. Hardly were the soldiers home from the war than the Government began ruthlessly breaking its promises to them. It relentlessly cut pensions, denied payments, delayed help and stood almost idly by while ex-servicemen died by the thousand. During 1929-30 the death rate for Great War veterans (for all causes) was about seven a day.

Research I did in 2016 for the centenary history of the Newcastle RSL sub-branch (contained in our book, The Hunter Region in The Great War) shows many disturbing similarities between the treatment of veterans today and those of 100 years ago.

One of Australia’s most highly decorated Great War soldiers, Victoria Cross winner Joe Maxwell, wrote in The Newcastle Morning Herald on Anzac Day 1931 that the plight of many returned soldiers was pitiful, “and stands as a monument of disgrace to a country for which these gallant fellows sacrificed so much”. Maxwell described a tour of the Depression-hit streets of Newcastle, where he found scores of ex Great War Diggers sleeping rough in parks.

“Near the gas works another “battalion” is bivouaced in dug-outs, shelters, and two hard-boiled members of the 18th Battalion have made their abodes in adjoining 6ft cement stormwater pipes,” Maxwell wrote. “The crowd of men congregated at the municipal tip near the Sports Ground recall memories of Egypt, with its scores of hungry natives salvaging the garbage tins at the AIF camps, for scraps of food. To add to the family coffers – as one fellow confided – they collect old tins, pieces of copper wire, and, in fact, anything which can be bartered to the second-hand dealer, who calls each evening.”

This general neglect of returned Great War servicemen was not confined to Newcastle. In 1932 the retiring president of the Coonabarabran RSL Sub-branch, Rev. Father C. Lonergan, wrote that the returned soldier was “without honour in his own country, and his fate writes a page in the history of this country of which no-one can be proud”. “Amid rapturous scenes at their departure, diggers were assured that: ‘living or dead, they were never to be forgotten’. They were to be placed high on the pinnacle of the nation’s gratitude,” Fr Lonergan said. “Bravely and faithfully the duty was borne, with well-nigh infinite patience and steadfastness, even when all round appeared to fail. The world proclaimed it! But the war was scarce over when a change seemed to set in. Public opinion forgot the promises and the cheers.”

Newcastle’s RSL journal complained about the government’s treatment of Diggers: “Departmental failings: No perspective, no imagination, no sympathy, no ability worth anything; and the Digger suffers”.

Hunter Region wartime leader Brigadier-General John Meredith wrote that men had returned “with their ability dulled by years of service and unaccustomed work and we find that they must be classified as perfectly sound, totally incapacitated, partially incapacitated, shell-shocked and recurrent sick”. “. . . these men who have sacrificed the best part of their life to the honour and glory of this glorious Commonwealth are almost starving. The streets of the towns and cities are full of Diggers who are unable to work owing to their disabilities, and whose pensions are not sufficient to keep them, are compelled to ask charity of the public, who unfortunately look askance at them, and they are fast becoming derelicts with no thought of the future. They start to wander from place to place, and also many of them are dying in strange places without a friend or relation near them,” Brigadier-General Meredith wrote.

That was in the Great Depression, of course, and the huge number of Diggers in need was greater than today when relatively few need support in an apparently prosperous country at a time when the traumas of military service are said to be well-understood.

While Australians properly pay their respects to the warriors of the past, they might care to spare some thought for those of the present, and to ask themselves whether the nation has learned from the lessons of the past.

Amidst the hymns and exhortations to never forget, it seems, something very important is being forgotten after all.