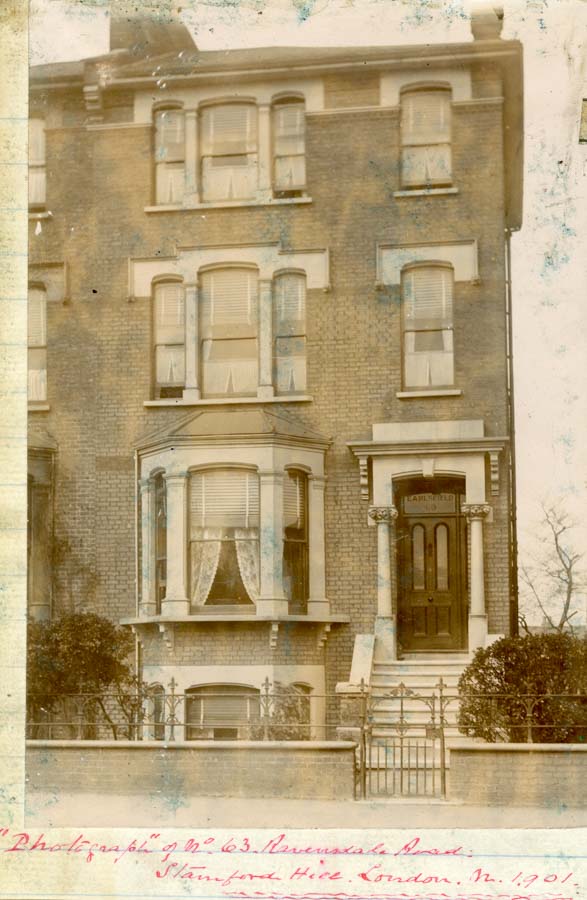

This rather melancholy epilogue to the logbook of Captain Robert Huddle – excerpts of which I have transcribed in other posts – finds the old seaman washed ashore in England, “a chronic invalid” on “a petty pension”. The volume ends with a pasted-in photo of his residence in London in the year 1901: 63 Ravendsale Road, Stamford Hill. I have looked on Google Earth, and the building looks almost the same today.

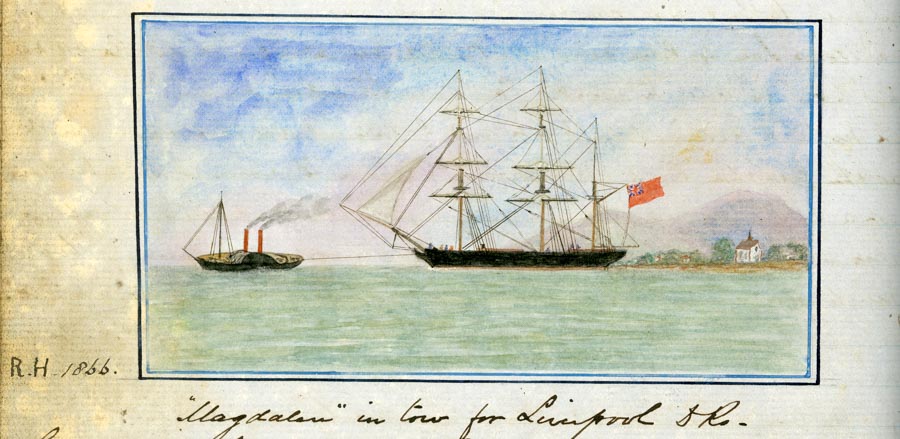

As the beginning to the end of this narrative I have attempted to set out in the preparatory pages some references to my voyages between the year 1856 and the date when I began to record in this log some impressions on the various incidents arising during my travels henceforward at sea. Some of them perhaps deserved more ample description than were bestowed on them at the time of occurrence. Be that as it may, they are in substance and fact memoranda affording some idea of much which I have seen of interesting things and places. What they lack in tendency to book-making by being faulty in denseness of description, might serve as it were a mirror reflecting in its varied aspects the different phases of life at sea and convey some information to my relatives and friends rather than afford reading matter to attract other interests. The daily notes throughout the pages correctly map the journeys which have taken me to many parts of the world and represent the more diversified portion of my career. Those relating to the time I put in as chief mate on board the barque Magdalen were uneventful and the time was exceedingly tedious, engendering in one a tendency to blunt his susceptibilities insofar as tempting me to set down in writing notes on much that such a dreary voyage familiarises one with. Other than my being nigh starved in this craft nothing unusual happened. After I bid her adieu my appointment to and service in the well-appointed Atlantic steamships in which I afterward served was distinctly a step in the right direction. It was a new departure in my experience. The duties of an officer in them were arduous, exacting and inseparable from considerable exposure to vile weather but the accommodation diet and other comforts they provided afforded a fair measure of content consistent with shipboard life. The time on board these ships was at all times more or less interesting, with amusements of some sort or other or with much that tended to rub off the rough corners and asperities of everyday life at sea.

My voyages across this familiar ocean ferry were notorious in having disagreeable weather for something like eight months out of 12: either gales of wind or – what is much more objectionable to the mariner – fog. The other notable incidents arising during these trips were the breakdown of the engines on board the SS William Penn, my attempt to board a derelict ship on fire, the stranding of the RMS Tripoli near Boston and a somewhat unique one on board the RMS Batavia. One of her saloon passengers died whose friends then on board were desirous that the body should, if at all possible, be retained on board till the ship arrived in Boston. It was decided to have a suitable box made and place the corpse in it immersed in whisky. By this means it was kept on board and handed over to its relatives in Boston. My cruise as chief officer in the steam yacht Hebe was an agreeable and interesting round of travel and up to that date was incomparably the brightest of any of my former ones. This cruise, as it afterwards proved, was responsible for imbuing me with a determination to quit the Cunard service, knowing as I did that further promotion than the second officer in it was denied me in consequence of my not having held previous command of a ship. This essential qualification was the passport to further promotion in this AI service.

In the diary of the RMS Brisbane it will be seen that I wrote more detailed notes which compare more favourably with the more prosy ones of former voyages and present a little of the sunny side of my travels, but one need not suppose on that account that my time in the Far East was all “couleur de rose”. A reference to the diary will show that I had privations and hardships there as also later on realising that residence in the East was not only endurable but at times delightful.

First glimpse of Singapore

My first glimpse of Singapore was in the Brisbane. It was decidedly pleasing when nearing the harbour. The beauty of the scenery dotted about the numerous islands which fringe its approaches, the green fresh verdure on them, seemed such a refreshing relief to one’s sea- wearied eyes to rest on. After a short stay in Singapore, where we were very busy furbishing up the Brisbane, the novelty of my new surroundings began to wear off and I did not jot down everything I saw there with that devouring speculative curiosity peculiar to the griffin. I felt I had come to stay in the East and if Singapore or any other place my travels might lead me to had any attractions future occasion might arise when I should perhaps see more of them.

It was from Singapore as a centre I revolved around as far as Cochin China, Hong Kong, Australia, Java, Madras Coast, Sumatra and the Red Sea – where I was shipwrecked – and again later on in the Straits of Banka I met another disaster which ended in my wanderings being confined to within a radius 400 miles of Singapore in command of the colonial steamer Pluto, an appointment that satisfied my aspirations as I knew if there was any enjoyment or the reverse of it obtainable during my stay in the Straits Settlements there was some chance of realising it. When I first entered the port of Singapore I had fairly high aims and not a few wholesome ideas as to ultimate success if I remained long enough. I had a mature experience and felt pretty sure it would be of use to me. The sequel to this narrative shows I was not incorrect for in the new duties I was destined to be employed in my experience served me in good stead. During my time in the Pluto I had many opportunities of travelling onshore in the Malay Peninsula, the climate of which is much hotter than in any other I had been in.

The country was then but little known. It was without rule and without roads. Slavery was rampant. Murder, robbery and arson were rife and piracy along the seaboard and in the adjoining rivers was of frequent occurrence. It was in November 1875 that the first British resident stationed there was murdered by the Malays. Shortly after this event a punitive expedition under General Colborne was dispatched to occupy the country. The troops advanced up the country as far as Kinta the capital of Perak in order to punish the Malays and occupy numerous posts throughout the state. The Pluto was actively employed in conveying troops, stores and government officials from Singapore and Penang to Perak where the authorities, both Imperial and colonial, were engaged in establishing a settled order of government. The Sultan and other headmen were eventually captured and in due time came a successful close to the campaign. Order was restored, or rather brought about, and the country brought under British control. On my returning to Singapore with the new colonial steamer Sea Belle in October 1883 I again voyaged to and visited some of the places in the Malay States. The country is now contented and prosperous with good roads and buildings, well-constructed railways, plantations and tin mines in all directions. In fact, everything shows evidence which bespeaks proper administration, indicating what advantage it has been to these native States and its people that the British power came to aid them and give them proper government.

Swallowed the anchor

In May 1884 my sea service came to an end and I, as it were, then swallowed the anchor by being installed in office on shore in the marine department, Singapore where permanent residence has its advantages certainly but it is a question whether these or its disadvantages predominate. The absence of any change of season – to one who knows what winter is – is monotonous. The round of sunrise and sunset at the same hour day after day all the year round with an equability of temperature varying so little as to be scarcely perceptible tends to induce so complete a change of habit in one which unfits them to adapt his system to or tolerate the radical changes of life which residence in England imposes on one without very considerable protest.

From 1874 to 1893 I was witness to rapid developments and improvement in Singapore. The place since the opening of the Suez Canal has become an important centre of commerce. It is the largest coaling station in the East and has seldom stored in its harbour less than 250,000 tonnes of coal, besides being the one point which all seaborne trade from Europe and India must pass on its way to China, Japan and parts of Australia. Large amounts of money have been expended on defence works for the protection of the place which has now become a powerful fortress. The strategical importance of Singapore has become so far recognised by the British government that expenditure from both the Imperial and colonial governments has been furnished with a lavish freedom with money for its defence. As a shipping port it has now the enviable reputation of being equalled by no other in the East. The island is picturesquely pretty and its city a flourishing one. The business part of it is on the sea-front and in the adjoining square are situated the banks and principle European stores. It is true there are parts of the town which have a wretchedly sordid and miserable appearance but once away from these districts there is much that is charming about the island.

My private quarters were in the Hotel de Europe and to my snug rooms there I was always eager to adjourn after my official work was done. From my balcony there, which faced the Esplanade recreation ground and the roadstead, I could lay back in the seductiveness of a long chair and survey with great interest between the hours of five and 7:00 PM such a series of kaleidoscopic views which for variety I venture to assert are not to be seen in any other place in the East that would match it during these hours save when a thunderstorm happens to upset arrangements. Every type of man and not a few women are to be seen there, from the well cultured European or American to the semi-savage pagan. The mixed nature of such a motley crowd one sees may be easily imagined when it includes Chinamen on bicycles with their long pigtails streaming a yard behind them, Siamese, Japanese and others on horseback and various coloured vehicles drawn by small and hardy ponies with Malay or Chinese coachmen and footmen conveying for display the most elaborately enamelled and vividly costumed members of the demimonde: Chinese, Malay and Japanese damsels in jinrickshaws and the European and Eurasian community in neat conveyances out for the evening airing and drive before dinner after the heat of the day, besides seeing football, lawn tennis and cricket. All these go to make up one of the most extraordinary jumbles of humanity which it would be difficult to match or meet elsewhere. The inhabitants of Penang and Singapore are mostly aliens to the colony: people who have come either from Europe, India and China for the purpose of seeking a livelihood in it. The aboriginal Malay, so far as he is interested in trade, has ceased to exist. Neither Penang or Singapore produces anything. Both towns are great commercial warehouses carrying on a business of buying, selling and packing and distributing to all parts of the world. The climate is healthy but trying and monotonous, making one feel liverish and sometimes swear at the place. Apart from the town of Singapore it must be admitted that its suburbs are charming. The houses occupied by the leading European residents are delightfully situated about two miles from the town, each standing in its own compound embowered in fernery amidst pretty lawns and beautiful trees forming a very attractive and pleasing picture.

The social surroundings lack nothing in the way of entertainment. There are plenty of amusements provided by those who can afford to pay for them: theatricals, concerts, picnics etc. There are excellent roads affording opportunities for driving and riding or bicycling. There are about 4000 Europeans in the place exclusive of the garrison. The Chinese predominate and have large interest there and they do a large share of the trade in the colony. They own the larger portion of the steam and sailing ships registered and trading in the port. Indeed the Chinese get the cream of the trade, make pots of money and many of them spend it freely. The Malay natives of the country are rather a lazy lot. They however make good sailors, are born pirates, incurable thieves and good liars. Singapore at any rate is not the place in which to see the Malay to any advantage. They are steeped in superstition, teeming in legendary lore to a degree that is absolutely incredulous to a white man. Their stories to listen to them would make one take a real long jump in his sleep if his constitution was strong enough to swallow the tales these people are fond of relating. Malays formed the larger portion of the crew in the SS Medina, Rosa, Minister Van Staat Rochussen, colonial steamer Pluto and Sea Belle.

In China and Japan

The most marked event during my time on shore was the two journeys I made to China and Japan, a recreation that was delightful to me. Japan as a holiday resort seemed just the place that hits the happy medium between over-liveliness and semi-dullness, affording one inexpensive comfort and luxuries without undue expense. To get about as I did and to see as much that was worth seeing could not be indulged in without a sufficient purse. This I had and felt these could be no real pleasure derived from my holiday had I to be perpetually counting the cost or consulting my pocket. Otherwise I should before journeying so far have had to be content with reading about such interesting places rather than have attempted to realise the pleasure of seeing them.

My disappointment was great, then as now, in not having this logbook with me then or during my voyage out in the Sea Belle from London to Singapore and my residence onshore there. Were my notes recorded in its pages during these periods they would, I believe, have afforded more interesting reading, particularly in reference to my visit to Japan where my associations were full of charm and interest. I met many Europeans there, some of whom I had known in the Straits Settlements, and in their company I spent a good deal of agreeable time and hope the day is far distant that I should know their hearty laughs – which attended some of the excursions we made together in Yokohama, Kobe, Osaka and Kyoto – were now pent in by a nameplate or weighted down with a headstone. Even though these may proclaim the virtues they cover, they are but poor consolation even when true which as a rule they are not. Still the memory of these bygone recollections cannot obliterate all the traces of my fondness for a country in which I spent many delightful months’ sojourn. The memory of it is pleasant to dwell on and no one begrudges me loving it all these miles away. The Japanese and his country has been described for all he is worth by many writers. For me to say more of him now I get broke up in no time. Concisely, these trips were a pleasant escape from my duties which failing health began to make tiresome. To get away from them and as it were to live in fancy at least under more leisured and picturesque conditions was as agreeable a change as it was possible I could experience after the enervating effect the climate of Singapore has on one. The inevitable result is that it becomes imperative one should seek a complete change to colder latitudes.

The necessity for such a change was in my case very pronounced. The handwriting on the wall indicated in no unmistakable warning that my time in the tropics was nearing its end. Something in my tone and general health that is really undefinable instinctively told me my active service was within measurable distance a foregone conclusion. My return from Japan and resumption of duty in Singapore made this later on more apparent and as previously mentioned I was sometime afterwards compelled to reluctantly take leave in May 1893 with the hope of recruiting my health and returning again to duty in Singapore for a few years further service. It was however destined otherwise for as the time was near that I should in the ordinary course have returned to my duties in Singapore my health completely broke down. Medical opinion then decided it was undesirable I should return to the East and recommended my retirement on pension. This was in April 1894. My discomfiture on receiving this fiat officially from the colonial office was complete, since when I have tried all I know to become reconciled to the usages of domestic life in England and have failed – besides arriving at the conclusion, rightly or wrongly, long residence in the East has ill prepared one to conform to the conventionalities of home life in this country and from choice I would rather have remained in the East: either in Singapore or Japan.

I have now summarised the contents of this log book and traced out the developments which have followed me from my boyhood to retirement. In concluding my remarks a few more words are wanting to complete my narrative. Briefly it seems to me a hard thing to have to say goodbye to it. The simplicity helps it too often to say and yet mean so much; still one has to say it to those scenes in which he has figured for so many years and at least has to seek that retirement which it should be good one ought to in enjoy a look forward to as the eventual reward of a life spent in a large measure in hard plodding perseverance. The net result of my labours, however, has resulted in my becoming a chronic invalid due to the contraction of ill health while serving under the government of the Straits Settlements, the after effects of which preclude me from participating in any of the pursuits of robuster health and unables me to realise any pleasure or advantages of retirement which is generally supposed to entitle one to. It is painfully irksome to find the exchange from an active life for one of by no means tranquil repose should become so void of pleasure as to afford no occasion in which I could rejoice over the allusiveness of the attractive portion of it. “The best laid schemes of mice and men gang aft agley.” They have with me, for ruined health, a petty pension and enforced idleness entail restrictions which become a sorry solace after so many years of active employment in an adventurous and somewhat perilous calling.

Robert Huddle,

Sidcup, Kent, December 1897.