In years long gone by childbirth was far more dangerous – to mother and baby – than it is in rich countries today. Not only was birth hazardous, but the early years of childhood were fraught with risk. Diseases now preventable ran rife. Without antibiotics, infections of all kinds could be extremely dangerous. Fire was used in heating, food storage and hygiene could be questionable and youngsters were often expected to do chores and tasks that exposed them to potential hazards.

The first few years were the riskiest, it seems. According to Newcastle City Council (NSW), 38 per cent of the 3300 burials conducted in the city’s Christ Church cathedral grounds in the 1800s were children under three years of age.

But funerals, it seems, could have costs attached. What did poor families do when they lost a child and couldn’t afford a formal burial? A recent correspondent, Mrs Helen Cliff, encountered this issue while doing some family history research. Poring over old and forgotten letters, she found a note to her from an aunt in 1966, thanking Helen for taking her newborn daughter to see her. The Aunt observed in her letter that the baby looked like Helen’s sister. Helen, it seems, had a sister, born in 1943, who lived just two hours.

When she pursued the subject with her aunt she was told that Helen’s grandfather had made a tiny wooden coffin for the infant and painted it white. The aunt had lined it with white fabric. Then, according to Helen:

My grandfather and his mate crept out to the Whitebridge Cemetery one night and they buried this poor baby on the edge of the eastern end of the Church of England grounds” – near the fence line but near enough to the family graves. I guess there was no money to bury them and that is why my sister (Marie) was buried this way.

This year (2022) Helen raised the topic with a cousin who surprised her by telling her that she too had a stillborn sibling – a boy – and that he too had been buried unofficially in this portion of Whitebridge Cemetery. Helen had been given to understand that the births took place at the home of an unqualified local “nurse”. She was wondering whether telling her story might lead to more information about similar unofficial burials.

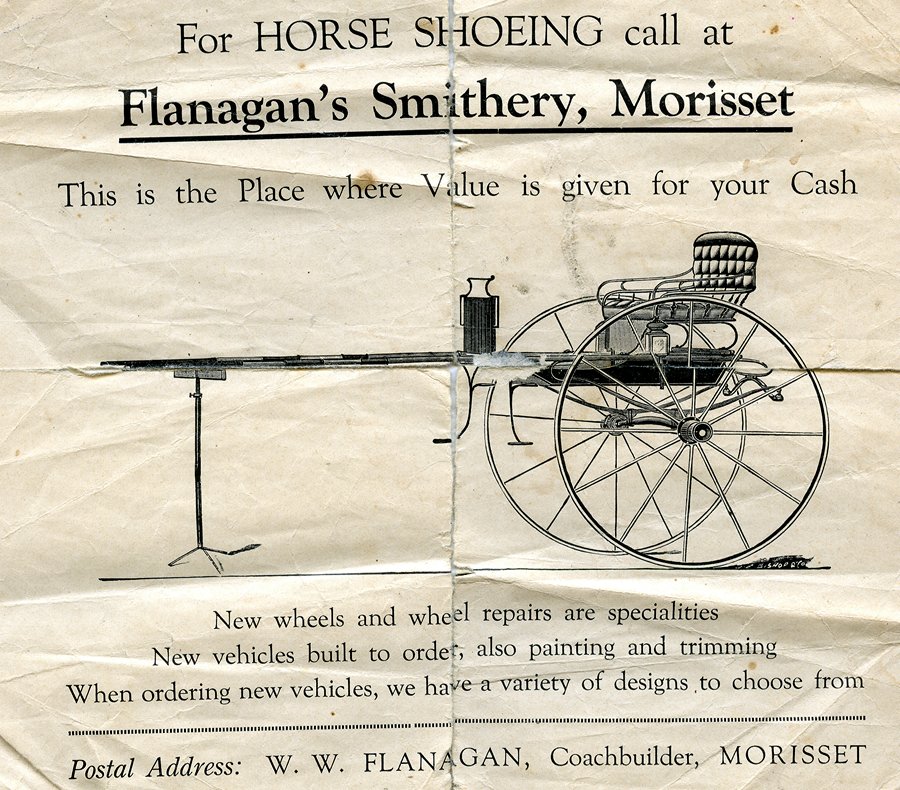

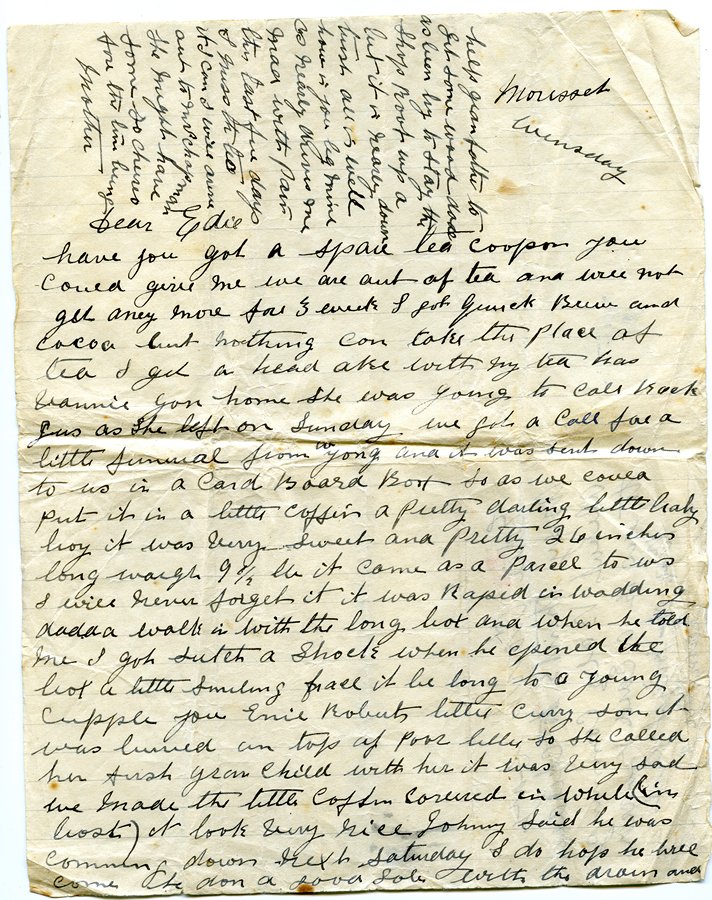

Helen’s story reminded me of a letter I have in my collection, found among some papers relating to the Flanagan family of Morisset, Lake Macquarie. The Flanagans ran a versatile business. They could shoe your horse, build you a new carriage or, if things came to their final extremity, help lay you to rest as undertakers. In the letter Maria Flanagan recounts a sad tale of a baby’s funeral. The letter is undated, but appears to be from the Depression or war years. A transcript of the letter follows:

Morisset, Wensday

Dear Edie,

Have you got a spare tea coupon you could give me?

We are out of tea and will not get any more for 3 weeks I got Quick Brew and cocoa but nothing can take the place of tea I get a head ache with[out] my tea.

Has Grannie gone home? She was going to call back just as she left on Sunday.

We got a call for a little funeral from Wyong and it was sent down to us in a cardboard box so as we could put it in a better coffin. A pretty darling little baby boy it was, very sweet and pretty, 26 inches long, weighing 9½ lb.

It came as a parcel to us. I will never forget it. It was wrapped in wadding. Dadda walked in with the long box and when he told me I got such a shock when he opened the box a little smiling face. It belonged to a young cupple. . . .

We made the little coffin covered in white. It looked very nice.

Johnny said he was coming down next Saturday, I do hope he will come. He done a good job with the drain and helped Grandfather to get some wood. [Dad?] has been trying to stay the shop roof up a bit. It is nearly down.

Trust all is well. How is your leg? Mine has nearly drive[n] one made with pain this last five days. I miss the tea. If I can I will drive out to Mrs Chapman, she might have some.

So cheerio for the time being.

Mother

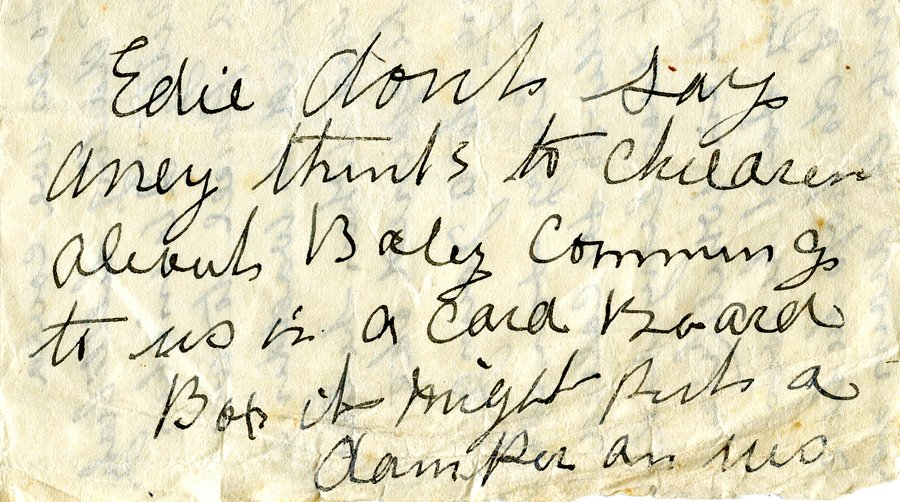

Edie don’t say anything to the children about Baby coming to us in a cardboard box. It might put a damper on us.

It seems surprising today, but until quite recently stillborn infants and “late miscarriages” in Australian hospitals were usually buried in unmarked shared graves, with a policy of attempting to prevent parents bonding in case this exacerbated the inevitable grief. As a result, records and resting places of such children can be hard to find. Helen was able to find both birth and death certificates for her long-lost sister but she doubted whether her own mother had ever seen these documents.

Attitudes have changed a great deal for the estimated seven stillbirths per thousand births in Australia today. New and more sympathetic guidelines have been adopted in clinical practice. And the high-profile support group SANDS offers counselling and advice to those who need it.

My brother died hours after birth in 1963 and they cremated him before my mother was out of hospital. She grieved for him for many years and in 2000 finally applied for his death certificate, no one had ever told her why he died.

Such enduring sorrow. 🙁