EASY credit is a two-edged sword. For most people in mainstream Australia it’s easy to borrow money, but for a great many it’s a lot harder to repay.

I remember the solemnity that accompanied the arrival of my parents’ first credit card. It was the 1970s and “Bankcard” was new to Australia. My vague memories of dinner table conversations are that this was an American idea, convenient but dangerous. Firm rules had to be established to make sure this powerful new genie remained a servant and never became a master. Bankcard purchases had to be closely monitored and the entire balance had to be paid off within the 30-day limit to avoid paying interest.

These rules weren’t hard for my parents to follow. My mother ruled the family finances – literally – with a ruler and blue and red pens in an exercise book. Once a month she sat at the table and tallied up the income and outgoings (my father was paid monthly) and delivered the verdict. Being a child I never realised how our actual diet related to this monthly exercise, at least during some periods. Early in the month, when the horn of financial plenty appeared to be overflowing, we might eat steak. By the end of the month, when the bottom of the barrel was being scraped, sardines on toast might make a meal.

The use of credit to smooth the peaks and troughs of family cash-flow wasn’t really an option in those times. Credit existed, of course: just in different forms to those most prevalent today.

It’s hard to imagine what Australia was like in the 1970s. I don’t want to overly romanticize it, but things were very different. The second world war had only been over for 30 years by the mid-70s, and Australia’s war-enforced self-sufficiency was still somewhat evident in the apparently thriving local and locally owned industries and businesses that offered a very wide range of career and work opportunities. But money wasn’t super-plentiful. My father moved employers mostly because he was offered a subsidised housing interest rate as an incentive to jump ship. I recall my parents giving thanks that the job my mother was obliged to quit when she became pregnant with me provided a superannuation windfall that became the deposit on a block of land.

Getting housing finance could be tough, a fact that led people to come up with creative solutions like building societies, credit unions and Starr-Bowkett societies, where you and other members helped each other raise the funds to build or buy at far more favourable rates and on better terms than the big banks were willing to offer.

Consumer credit took simple forms. Like the tab my grandparents had at their local grocery store. The store owner let the tab go only so far before clamping down. Only when the tab was cleared could they start running it up again, which sometimes meant my grandfather was forced to unhappily forego his tobacco.

Pawnshops, of course, provided an avenue for those willing to “hock” some item of value, handing it to the pawnbroker in return for a loan that could be redeemed for a fee that included a margin for the lender, who had the right to sell the item if you failed to redeem it. This article, about famous Newcastle pawnbroker Dinny O’Brien, gives some idea of the business.

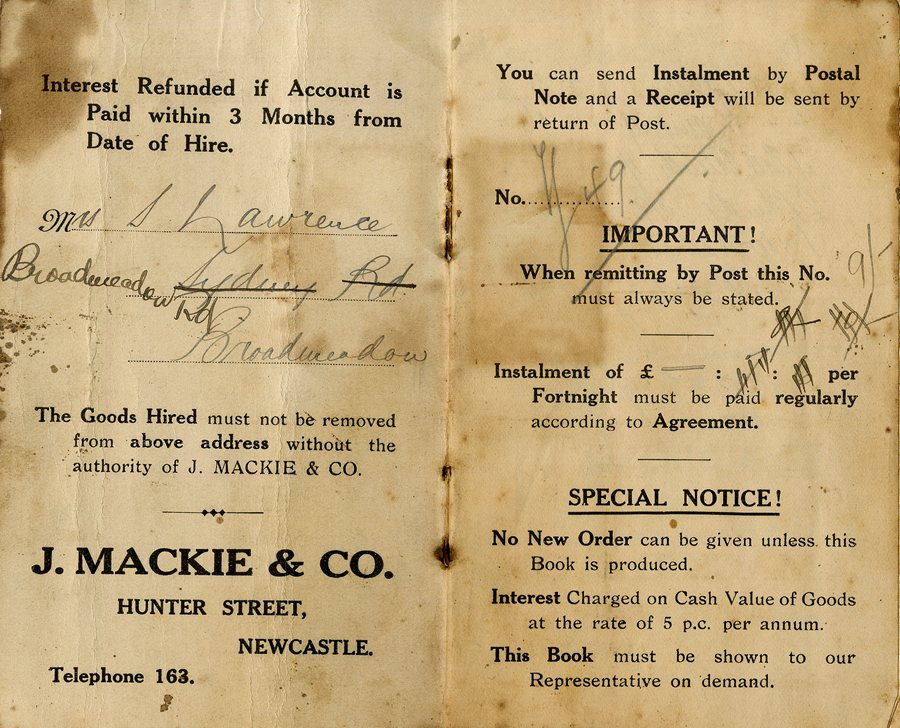

For bigger items there was lay-by, hire-purchase and rental. “Lay-by now for Christmas”, said the signs in all the big stores. “Laying by” meant what it said. You paid a deposit and the item was “laid by” for you until you managed to cough up the balance. The opposite of “After Pay” in our modern times. Hire purchase was different again. You were allowed to take the item home but you had to make regular payments including interest. The item was not yours until you made the final payment. If you stopped being able to make payments, you risked having the item removed from you. You weren’t allowed to sell it, you had to let the owner have access to inspect the item at any time and you had to insure it with whatever company stipulated by the owner.

Sometimes you could rent a major item, like my grandmother rented her first TV. Whole businesses were built on renting major appliances, I recall.

My parents routinely used lay-by. Bit by bit they furnished their house then added some luxuries, like a stereo, a bar and a chest freezer. Every purchase was carefully discussed and the pleasure of owning was deferred.

Another, more obscure credit product was known as the “cash order”. Cash orders were mostly issued by commercial firms to people who wanted immediate use of products but could only afford to pay them off over time. Customers bought a cash order, paying five percent up-front and agreeing to pay the rest off in five per cent weekly installments. (The first actual installment was also usually paid up-front.) A customer took the order to a retailer, which may or may not choose to accept it. If the order was accepted as payment, the retailer then claimed the sale amount back from the cash order company, less a discount. This represented a reasonably handsome profit to the cash order company. In Newcastle a Workers Cash Order company operated from an office above Krempin’s seed store in Hunter Street (no connection with that firm) and its products were used by poorer families to buy household necessities, clothing and footwear.

People had cheque books and wrote cheques routinely. But cheques could “bounce” if there wasn’t enough money in the account they were written against. Cash was king in those days, if only you could get your hands on it.

These days when I hear people – and I hear many of them – complain that they can never afford to make more than their minimum monthly payment on their credit card debt, I think of my mother, her exercise book, her ruler and pens. She was absolutely right about credit being convenient but dangerous – and deliberately so. Watching an episode of The Sopranos once I saw how the mafia lured people into their gambling dens, persuading them that they were high-rollers who deserved the best things in life. It’s a standard shtick for organised crime. Get your victims over their heads in debt, drain their bank accounts then take their cars, their homes and their businesses.

Banks and credit card providers are, in my opinion, somewhat similar to the mafia in that respect. They are happy to entice you into debt and they prefer you to go in so deep that you can’t clear the balance at the end of the month. That way you have to pay them interest at the high rates they nominate. I’ve met scores of people in this position. One old lady told me she’d been paying the minimum monthly sum for years, ever since she used her credit card to fund her daughter’s wedding, long ago. At the moment in Australia, the average credit card interest rate is just under 20 per cent, so you can see what a massive earner this is for the banks.

My parents were right in the 1970s when they observed, while contemplating their first credit card, that this was a potentially helpful genie with a dangerous downside. In the 2020s, Australia is a land of debt traps. Gambling ads are pushed down our throats, luring people – mafia-style – into the dens. Young people are told they must have university degrees to stand a chance of being employed, and these degrees now cost tens of thousands of dollars. Many graduates are stuck with student loans (courtesy of the government) that might not officially carry interest rates but which are indexed for “inflation” in a way that means they really do. With the housing market turned into a giant casino, anybody looking for shelter has to compete with foreign nationals and other investors, all driving prices up, inflating the balance sheets of the banks who as usual are laughing all the way to the bank.

The debt genie, I’m afraid, is out of the bottle and running amok.

I have been saying for more than a decade that somebody is vacuuming up all the money.

When physical money is no longer part of the economy the world will end with one power outage or computer hacker attack.

Money was always about a promise to pay the worth of the “note” or coin.

When the promise is removed money has no further value when your bank balance suddenly vanishes.

Smart phones are only smart while they connnect to another computer that holds your history.

My wife & I purchased our first (and only) house in 1974 however obtaining a loan was difficult. My wife worked for a bank but they didn’t recognise her income for the basis of a loan. I was a part time student however my salary was not high enough to justify a bank loan but too high to obtain a low income loan from a Building Society. Fortunately the bank changed its lending policy and my wife’s income was counted towards our loan and we moved into our house on the weekend of the Signa Storm.