Thanks to Brian Robert Andrews for correcting and informing this text.

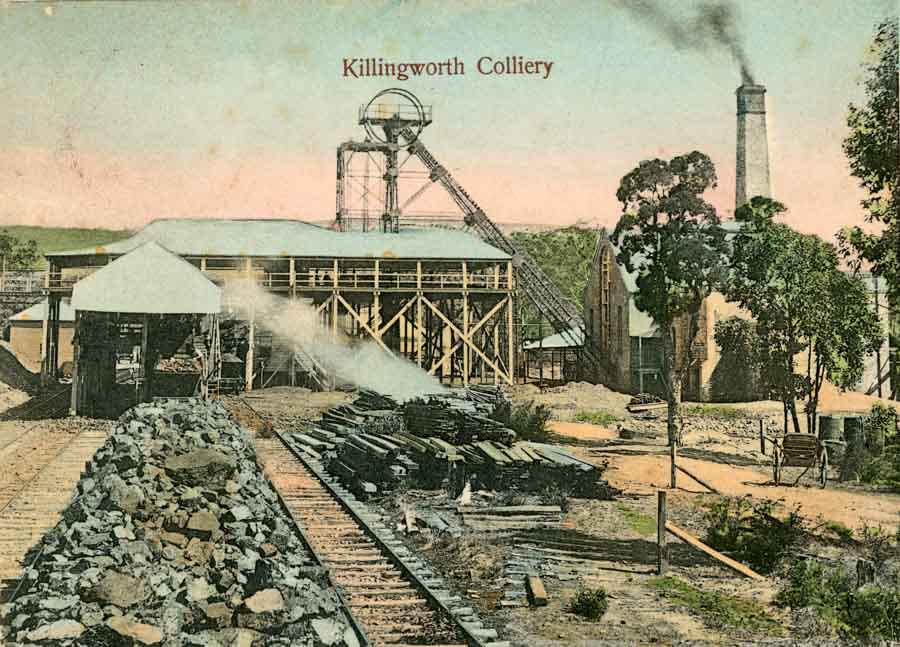

At 5.25am on December 7, 1910, people who lived near Killingworth, NSW, were awoken by a huge, ground-shaking explosion. As they looked outside, they saw a great black cloud of dust over the area of West Wallsend-Killingworth Colliery and immediately guessed what had happened.

The colliery had exploded, hurling dust and debris about 300m into the air. Fortunately the mine was not working at the time. It had been in care and maintenance for two months, and the deputies and maintenance men who were due to enter the mine that day had not yet begun their shifts. Only one young man – Herbie Watkins, aged about 20 – was present at the mine at the time. He was tending the boilers above ground, not far from the mouth of the pit, when he heard the rumble underground. He wisely ran into the bush.

Killingworth resident and mining historian Brian Robert Andrews told me that his father and grandfather both heard the explosion and went to the colliery. [As a sidelight, Brian said that when he got out of bed on the morning of January 8, 1979 – the day that West Wallsend No. 2 Colliery blew up – his father was having breakfast. Brian’s father told him the pit had blown up. When Brian said he doubted, it his father insisted he had heard exactly the same noise that day as he remembered hearing in 1910.]

The only casualty of the enormous explosion in 1910 was a pit horse named Splash. The horse, who was underground in the stables, survived the blast but was killed by the toxic gas from the mine.

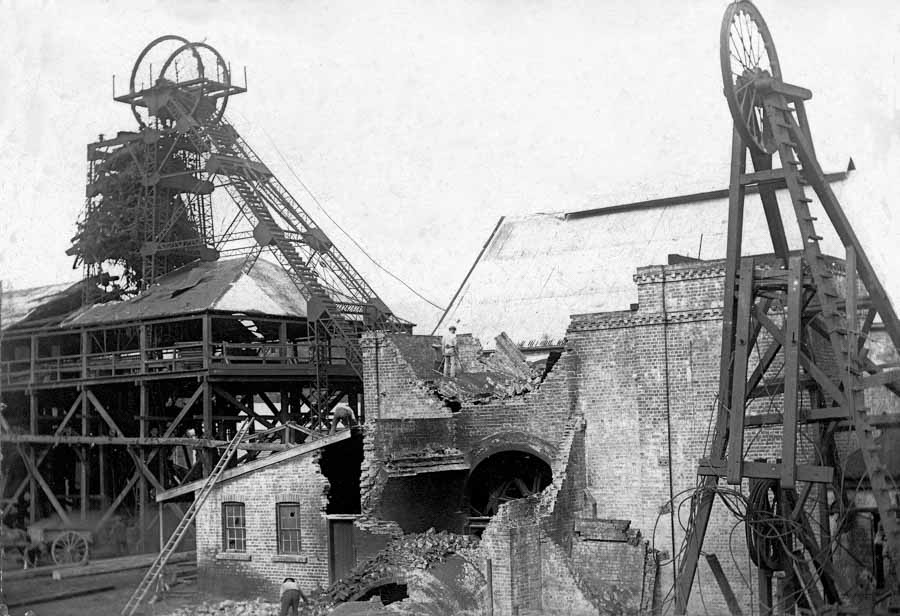

A press report at the time described how the explosion was followed by “a clanking of huge masses of iron and a crash of falling brickwork”.

The black column rose higher and higher, and then the smoke line drifted into the wind, and settled gradually over the surrounding landscape. The black column was coal dust, as fine as flour. It spread a black pall over trees, shrubs, and grass and lay inches thick on the football ground, which adjoins the pit-mouth. The employees living close to the shaft stood aghast for some time, and gradually summoning up courage, although anticipating a second explosion at any minute, proceeded cautiously to the scene of the uproar.

“A huge gun-barrel”

The scene at the shaft head was a most extraordinary one. Somewhere down in the bowels of the earth, six hundred and twenty feet below the surface, probably, in one of the many bords or side cuts from the main tunnel, an explosion had occurred, the cause a mystery, and rushing with a deafening roar along the drives had stirred up vast clouds of powdered coal dust, which, when in motion, caused a still greater explosion than gas, with a force which shook the earth. The explosion rushed along the main tunnel and the ventilation shaft, apparently carrying everything before it. The main shaft acted like a huge gun barrel 10 to 12 feet in diameter and 620 feet long. With another deafening roar, the great charge burst up the shaft, carrying with it an enormous projectile of shattered coal, cages, iron, and tangled steel cables, weighing in all close upon 40 tons.

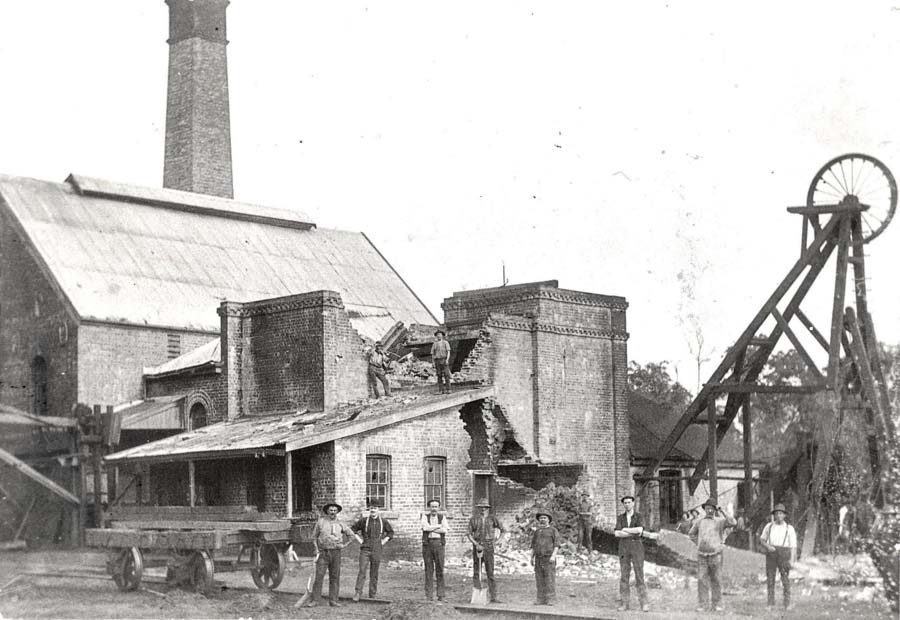

The debris from underground was flung into the poppet head above the mouth of the downcast shaft. Somehow the framework of the head withstood the force of the impact and retained the twisted and jammed material. The nearby Killingworth B shaft was also wrecked. Its wooden framework was lifted and dropped, and the ventilation fan tunnel smashed. The press report continued:

The precautions taken to prevent a spread of the damage included the temporary sealing of the main with canvas and large length of timber. A temporary canvas stopping was erected in the ventilation tunnel, and in order to save the men working on this from being overcome by fumes a continual spray of water was played into the tunnel and on to the canvas. The whole of the surface buildings were covered in coal dust. Nearly all the windows were broken, and the structures had the appearance of having been on fire. This, however, was owing to the coating of coal dust. The uprights of the main framework were caked with coal dust at least half an inch thick.

The “after-damp,” or bad air, was present for some time after the explosion, some of the workers being slightly affected by it, and this would have made it practically impossible for any rescue party to have descended the pit had there been any men below when the explosion occurred.

It was not until June 14, 1911 that the seals were taken off the shafts and men cautiously made their way back underground. By then the fan, winding gear and pit-top had been repaired.

Caged mice and canaries

The inspection party found the shaft stripped of guide ropes. Debris littered the pit bottom so there was barely room for the men to crawl past. Blockages were everywhere and the pit was full of gas. Working with the constant fear of gas and risk of more explosions, the men gradually de-gassed and cleared the bord section. Caged mice and canaries were used as monitors of air quality: if they died, the men would have to leave quickly. The mine resumed production, albeit on restricted output, on August 28, 1911.

The mine closed again in the early years of World War 1 and was then reopened and closed a number of times before being mechanised in 1950. It operated from this time for six more years before again being closed.

Brian Andrews told me that his grandfather helped remove the debris from the headframe in December 1910, using a bullock team and then a locomotive.

The cause of the explosion was never really established, despite a Royal Commission into the incident. The commissioner visited the mine twice, in July and September 1911, and the formal inquiry began on January 3, 1912. The Commissioner presented his own theory on the disaster, speculating that the ignition of gas probably happened in an area of the mine which had been sealed off with brickwork. This theory needed to be either proved or disproved, since other similar areas existed in other mines. An inspection team went into the mine during the Easter holidays and the members were unanimously satisfied that the commissioner’s theory was wrong.

Brian Andrews noted that: “West Wallsend – Killingworth Colliery was one of the first in Australia to use oil flame safety lamps extensively in its underground workings and at the time of the explosion no naked flame lamps were used at the mine – safety lamps being used in all places except the pit bottom where electric lamps were used”.

Brian has suggested that Splash the pit-horse “actually caused the explosion by being agitated by the lack of oxygen due the fan being off”. “He would have been stomping the floor and a spark from his shoe would have set off the gas which turned into a coal dust explosion, which obviously started at the bottom of the upcast shaft, went along the return and into the intake and expelled up the downcast shaft,” Brian wrote.