When Neville Chant started work as a clerk at the BHP Company’s Newcastle steelworks in 1936, he was allocated to the correspondence department as a mail-room boy. He’d just finished his school leaving certificate and he started at the BHP just before Christmas. It was a different world from that of 2021, but although communications technology might seem primitive compared to today’s, it was capable of great efficiency.

While BHP’s headquarters were in Melbourne, it had important interests in many parts of Australia. The BHP steelworks and its satellite industries were a huge presence in Newcastle, dominating the city’s commercial life in many ways. The company’s ships brought in thousands of tons of raw material and took out huge quantities of finished steel products. All this activity generated a colossal amount of correspondence, some of it within the steelworks itself, some of it with head office and some of it with customers and suppliers all over the world. All this was recorded on paper – often in triplicate, and meticulously filed so that any memo, letter, quote or invoice could be retrieved quickly and accurately as required.

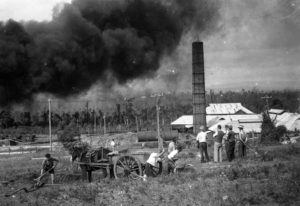

At the time Neville started work in the correspondence department of the Newcastle steelworks, he said, it employed about 14 people, including six mail-room boys, two of whom were occupied with internal mail on the sprawling steelworks. These boys did two daily runs around the whole plant, delivering and picking up the hundreds of internal memos that kept different parts of the business in touch with each other’s activities. Other boys had to carry the daily bags of mail between the works and the Tirrikiba Post Office – a post office that was built with the needs of the steelworks and its related industries especially in mind. Indeed, BHP funded the construction of Tirrikiba at the end of Crebert Street. The name was chosen because it was understood to be an Aboriginal word meaning “place of flame” – a reference to the night-time glow that surrounded the always-busy factory. The post office opened on November 1, 1921 and was renamed Mayfield East on August 1, 1952. From the start, Tirrikiba was equipped and staffed to handle the fastest communications then available for the benefit of BHP – Morse telegraphy.

According to Neville, Tirrikiba was the last building in Crebert Street’s southern side, and he said all the houses on the northern side from the post office up to Mayfield East School were “BHP houses”. Neville, who frequented Tirrikiba on BHP business, said the company sent “umpteen telegrams a day” and after hours it sent “lettergrams”, which were like telegrams but much cheaper. These went overnight and were received at the other end next morning.

After collecting bags of mail from Tirrikiba, Neville had to sort out the private mail from the company mail, which was opened and sorted by the head of the correspondence department. All letter mail was then registered and delivered by the mail-room boys. At lunchtime, the interstate mail arrived by taxi from Newcastle Post Office. Express overnight delivery envelopes had a blue band around them, and cost an extra fourpence. Posted at night in Melbourne, express overnight mail came to Newcastle on the “Flyer” (the fast train from Sydney) and was picked up at lunchtime. “It never missed,” Neville said, admiringly. “We sent ours at 3pm and it got to Melbourne next morning.”

Original copies of all mail was filed by the four filing clerks in the 20 four-drawer cabinets reserved for current correspondence. When no longer current it was transferred to the records room into numbered boxes, and when the time came it was shifted to an offsite records room at Shortland, near the golf club. Neville often had to go there on Monday mornings to collect old letters that were needed by somebody on the plant.

Many of the forms that were so meticulously filed were specific to a particular BHP department, so the plant had its own printery where three men hand-set every kind of corporate stationery required, from coal hopper tickets to inter-office memos.

After six months in the mail room Neville moved to the shipping department where he worked until the end of 1940 when he went back to head the correspondence department until he left the steelworks in 1945. He said the training he received at BHP stood him in good stead in his next job, at Hely Brothers – timber merchants at Hamilton. Not only had he learnt typing, shorthand and book-keeping, he had gained great knowledge of the working of the harbour. “I learnt how to handle bills of lading, manifests and all that type of stuff,” he said.

Neville found the shipping department very exciting and interesting. “Newcastle Harbour was alive with ships,” he said. “There were so many shipping companies in Newcastle. McIlwraith McEacharn, Huddart Parker, Australian Steamships, Union Steamships, Interstate Steamships, Adelaide Steam, Melbourne Co, John Reid. Foreign boats were looked after by a few shipping agents.” His daily job began with a visit to the wharf of the Newcastle and Hunter River Steamship Co to pick up the manifest of goods delivered for BHP. “They had a separate manifest, hand-written in Sydney, for all their consignment. You also had to look on a board of flat iron among maybe 30 other sheets just in case a late manifest came on,” Neville recalled. “You’d go back to the town office with the manifest then ring the transport department and tell them how many packages there were; their sizes and weights, so they would send trucks for them. Then you’d ring the store to tell them what was coming in.”

He recalled the ships, the Gwydir and the Hunter, then the Mulubinba and the Karuah, then the Kindur, which used to bring up heavy lifts and deliver to BHP’s own wharf for direct unloading. “The Hunter Rivers Company’s wharf had a roof, and the goods were unloaded with a ramp through a door in the ship’s side. There were no overhead cranes there,” he said.

Every week the harbour dues had to be calculated on all the incoming and outgoing cargo, and the amount had to be paid to the Maritime Services Board. “A ship with 5000 tons of ore, charged at four-and-a-half pence a ton, added up to real money,” Neville said. He spent most of the years of World War 2 heading up BHP’s correspondence department at a time when Australia’s economic sinews were strained to the limit. The head of BHP, Essington Lewis, was in charge of Australia’s munitions program, and Neville said the chiefs at BHP at that time were “pretty tough roosters”. Messages came into the department in code. There were two codes, with their own keys, and Neville’s department had to decipher them. News of the sinking of the company’s ships, Iron Knight and Iron Chieftain, came in by coded message and Neville remembers finding the shocking news hard to believe. “The big boats carried a crew of 48, and they went out in groups, with paravanes fitted for protection against mines, and with four-inch guns hastily mounted. The engineers were in charge of the guns. It got that way you wondered, whenever a ship left, whether it would make it through,” he said.