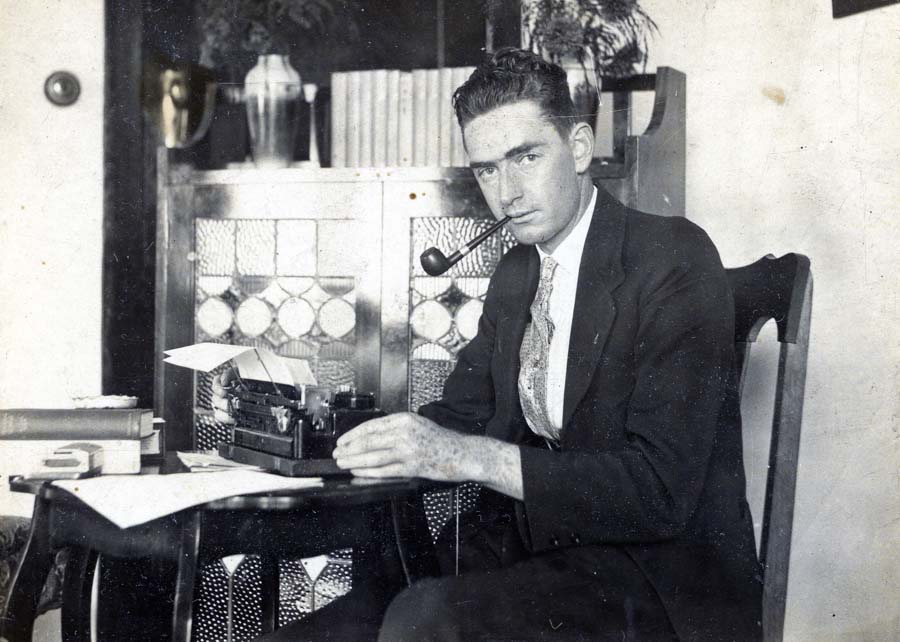

I am obliged to my friend Elaine Sheehan, the daughter of Charlie Thompson (who, coincidentally, once lived next-door to my mother), for access to many of the documents relied on for this article.

One day in June 1932 Newcastle Sun journalist Charlie Thompson, then living in Denison Street Mayfield, received a surprising letter from a neighbour in nearby Dora Street.

The author was a retired Victorian detective, Alfred Stephen Burvett, who had a tempting proposition for the 28-year-old journalist and budding author.

“My daughter,” wrote Burvett, “has just read out to me an article of yours in this evening’s Sun. From that I gather that you are an author. Well as such, I take it that you must gather your correct facts. Now if you wish to put your abilities to something substantial then call on me”.

In his letter, Burvett told Thompson that he was “for 33 years the leading detective in Victoria”. He wrote that he had kept comprehensive files on all the cases he handled over the decades and offered to make them available to Thompson.

.

“My manuscript relates the cases according to the true facts, giving names and dates. I prepared them as my life recollections but they are capable of being turned into much more, either in newspaper serials or in book form by either a journalist or author. Now if you care to call on me we can talk the matter over. I can be seen daily between 2 PM and say 5 PM or in the evening,” the former detective imperiously concluded.

Thompson’s reply has not survived, but he must have been keen to make contact, as Burvett’s next letter indicates:

Dear Mr Thompson,

I have just received your letter, and the contents has afforded me very much pleasure. I am very pleased indeed that it has been my good fortune to get in touch with you. I feel sure that you are going to make a success of the publication. In this respect I assure you that I shall feel just as much concerned that it should turn out so for your own sake in every sense as mine. Therefore “good luck”. Now by this morning’s mail I have received all the original manuscripts – from articles 1 to 35. They are in the order as it occurred to me to write right onto the typewriter, but, I have not revised them. I’ve not even read them over. In addition to these I can easily contribute practically any number of other true cases. Realising that the sooner you receive the complement of the cases already typed, I’m sending the lot around to you now. I would call myself but anticipate that you might be out, or possibly I might disturb you in other work. Finally, I may say that as my time is entirely my own, I can place myself at your disposal at any time and any day, to collaborate in compilation or supplying of any further information you may need.

Yours Faithfully,

A.S. Burvett

Burvett, and the relationship between the two men that grew from this correspondence was described by Thompson 18 years later in an article in Famous Detective magazine.

.

“ . . . there were times in our association when I did not think Burvett was a human being,” Thompson wrote. “At other times I found him intensely human. There were occasions when I was scared stiff of him, and other moments when I would cheerfully have murdered him and danced on his grave for 10 minutes each day.”

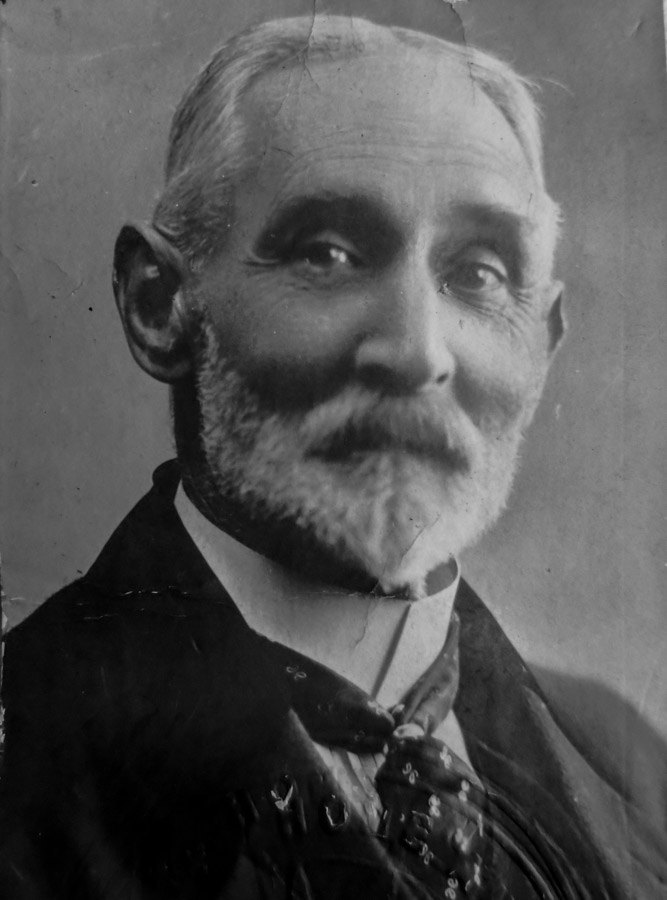

Thompson wrote that Burvett “personally regarded himself as Victoria’s greatest detective”. He described the former detective as: “A well-educated and cultured gentleman, dapper in dress, a trifle vain, an accomplished linguist, quiet-spoken at times yet apt to blaze forth into tempestuous anger, intolerant of fools, yet patient with them, brave as a lion, absolutely incorruptible and 100 per cent honest.”

Alfred Stephen Burvett was born in Barking, England, in 1860. His father was a wine and spirit merchant and his grandfather was a lawyer in London. He had a sister, Alice Sydney Burvett, who was born in Sydney, Australia in 1857.

While young (aged about 11), he was taken by his parents to France and attended St Malo College, Brittany. The family was in France during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and a fortnight after the revolution that followed the end of that war they moved to Paris to live. He described finding the city in “a most lamentable condition”, not because of the Germans but because of the depredations of the “revolutionaries” who had ransacked many houses.

Interpreter for Scotland Yard

During his 12 years in Paris Burvett took a job with the White Star Shipping line as a clerk, then later in foreign money exchange. Here he was exposed to the practices of forgers and scammers of various kinds and his dealings with currency fraud matters brought him into contact with police and detectives in both France and England. He was said to have worked as an interpreter for visiting Scotland Yard detectives, who might not always have wanted to take the local police into their confidence.

His sister Alice, meanwhile, had made a name as a concert pianist, and she and her mother hatched a plan for a musical tour of Australia – which they apparently imagined would earn them money. Their plan involved taking Alfred, then aged 23, as tour director, a post he assumed with reluctance.

Burvett wrote that the family arrived in Melbourne aboard the ship SS Sorata a few days before the 1883 Melbourne Cup. Shipping records show the Sorata arriving in Melbourne in late October of that year, carrying among its saloon passengers a Mrs Burvett (Clara P.), a Miss Alice Sydney Burvett and a Mr Alfred S. Burvett.

The musical tour was not a financial success, however. Indeed, Burvett was later to assert that Alice’s decision to return to the country of her birth resulted in her “ruin”. They did not make the fortune they expected. In fact they lost money and were forced to remain in Australia.

The lack of financial success of the tour meant that Alfred needed to find work. With considerable front, he applied to the Victorian Criminal Investigations Bureau for a job as a detective, citing his work experience in Paris as qualification. It was a matter of great pride to him that he was actually appointed – on April 19, 1887 – without first having to work his way through the uniformed police force. After just eight months in the job he quarrelled with his boss, Superintendent Kennedy, who gave him a savage carpeting. According to Burvett’s account, he had been sent to watch a noted criminal, but was temporarily blinded by a “north east dust storm” and lost the man. “I reported the matter to Kennedy, who took it very badly,” Burvett was reported as saying. “My early training would not permit me to accept being spoken to in such a way, so I promptly resigned.” He had already trodden on a few corns in the department and this, coupled with his loss of seniority by leaving, cost him dearly when he was induced to return on March 9, 1888. Kennedy, he said, had called him for a meeting, apologised handsomely and promised there would be no further trouble between them.

Burvett played the press very well, as can be seen in an article about him in the Melbourne Punch of October 31, 1889. Aged just 28, and only two-and-a-half years into his career as a detective, he was lauded in the article which listed a string of several cases he had a hand in solving. “The few cases given above, not to mention many others we could name did space permit, make up a list that few officers with the same length of service can boast of. We have not the slightest hesitation in predicting a bright and brilliant career for this popular young detective should he elect to remain in the police force”.

Burvett’s career as a detective had its ups and downs. He was highly successful and popular, to the point that his name was often seen and celebrated in the press.

He was stationed at the Victorian town of Benalla for seven years from 1893. It may be significant that this is the year in which Superintendent Kennedy – Burvett’s patron and hirer – retired. After his stretch at Benalla, Burvett was called back to Melbourne in late November, 1900. At a function held in his honour at Benalla’s Star Hotel, Burvett made it known that he was not keen on his impending transfer to Melbourne, which would come at a “certain financial cost”. Colleagues wished him well, especially uniformed officers who said that Burvett, unlike many other detectives, was often at pains to ensure that the regular police got their share of credit for the cases in which he was involved. Burvett said he had not particularly enjoyed the move from Melbourne to Benalla seven years before, having been born and bred a city dweller, but he clearly developed a liking for the place.

In March 1904 Burvett was declared insolvent. The Melbourne Argus reported on March 10 the reasons that the detective had “borrowed money at heavy rates of interest and having become guarantor for other persons and pressure of a creditor”. His debts were listed as just over 317 pounds, and his assets at 99 pounds. His pay, as an ordinary constable, was 9/6 a day, with 5/6 additional detective allowance. He clearly considered this low pay as a humiliating slight, and his supporters in the press agreed.

In 1906 he was recommended by the commissioner for promotion, but this was refused because the police force adhered rigidly (although there were rumours of some resented exceptions) to the principle of seniority in promotions.

Burvett threatened to resign from the police force a second time in July 1913, aged 58 and after 26 years as a detective. This was in protest at other detectives being promoted ahead of him on the basis of pure seniority. A strident campaign in his favour was mounted in the Melbourne press.

The department relented, promoting him to the rank of senior constable on February 1, 1914, and then to detective sergeant on September 17, 1914. By then, however, Burvett had had enough of the job.

He transferred to the Note Issue Branch of the Commonwealth Treasury on December 2, 1915, in time to become a key player in a major wartime High Court case – Farey v Burvett – which reinforced the power of the Commonwealth to fix maximum prices of key goods, in this case bread. He retired from government employment in 1920 at the age of 60. He worked as a private detective for some time before retiring for good and moving to NSW, first to Sydney, then to Newcastle, and later back to Sydney where he was to die in 1940.

While he was living in Newcastle – in Dora Street, Mayfield – he wrote his letter to Thompson. Thompson described his first meeting with Burvett as follows:

I made an appointment with him for 2pm a couple of days hence, and right on the dot I presented myself at his home in Mayfield. I was shown into a room and within a few minutes Burvett made a sort of ceremonial entry and greeted me gravely but pleasantly – something like a duke greeting his new secretary. I was immediately struck by his appearance. Dressed in black, he wore a cravat which was held with his dead wife’s wedding ring instead of being knotted. His hair was almost white and he had a white moustache and trim, pointed beard. He produced a wad of typed material which he said contained some of the cases he had handled. It was all written in the first person. He proposed that I should take it away with me, turn it into the third person, and that I should write a book under my name and the proceeds from the sales, if any, should be divided equally between us.

Then, Thompson wrote, came the “restrictions and directions”. Nothing was to be added and nothing was to be taken away. No slang was to be used. Burvett was not to be portrayed as a Sherlock Holmes style sleuth. Burvett warned Thompson that he had already terminated an arrangement for publication of his cases because the writer retained to edit the material had used the word “barked” when describing Burvett questioning a suspect.

Thompson wrote that he had many meetings with Burvett and his daughter Dorothy, finally arriving at a form of document that both were satisfied with. It was left to Thompson to find a publisher. But Burvett was impatient to see his book in print, and only about a month after the manuscript was posted from Mayfield, he went to Sydney to deal directly with the publisher himself.

What transpired I do not know, but I do know that he came away with the manuscript under his arm. This annoyed me and I wrote to him and told him that he should have left the matter in my hands to negotiate. I added that I would negotiate with another publisher, using the carbon copy. Back came a prompt reply that if I attempted to do that he’d issue a writ out of the Supreme Court to restrain both the publisher and me from using his material. I wrapped up the carbon copy in a neat parcel, added all his record still in my possession, and mailed the lot to him. I’d ‘had’ Alfred Stephen Burvett and he could have his life story to what he liked with.

Burvett moved to Sydney and the pair had no further contact. But when Burvett died in 1940, Thompson heard the news and began wondering whether he could now make use of the material he had spent so much time on, back in 1932. He found Burvett’s daughter Dorothy, who forwarded all the material back to Thompson.

“I sighed over the manuscript,” he wrote. “All my original work had been discarded and Burvett had had his cases all retyped into the first person”.

Thompson set out to publish the cases, one by one, in a small Sydney-based magazine called Famous Detective, published by Frank Johnson. They began appearing in 1947 and ran until about 1952.

As Burvett had intimated to Thompson when they first made contact, some of his cases had previously appeared in print in Smith’s Weekly and also in the Sydney Sun – before the feisty former detective argued with the editors and withdrew his manuscripts.

It isn’t known what became of the material that Thompson used to collate the articles he had published. But in the State Library of Victoria a typescript entitled Crimes and their Detection carries the handwritten note by Burvett’s daughter Dorothy – dated February 4, 1954 – that the document is, “to the best of my knowledge, the only one in existence”.

The preface of this document, written by Burvett himself, notes that: “the actual task of writing and editing my cases has been done by my young friend, Charles K. Thompson, and my daughter, Dorothy Emma Burvett, and their task has been no easy one”. The document appears to be the source of the articles that Thompson had published in Famous Detective magazine.

Burvett’s family life was marred by tragedy.

Ten years after he arrived in Australia, on October 6, 1893, he married Marla “Dolly” Honeyman. Burvett was then aged 33.

The couple had six children. Their three sons were Alfred Sydney, Herbert Henry and Reginald Stephen. Their three daughters – Clarice May, Irene Elsa and Dorothy Emma.

Marla Burvett died on November 26, 1913.

Burvett’s two eldest sons were born in Benalla, and they both enlisted to fight in World War I. He maintained a close correspondence with his namesake, Alfred Sydney, while he was away on active service. Alfred Junior’s letters to his father are preserved on the website of the Australian War Memorial.

Alfred Sydney “Sid” signed up in March 1915, aged 20. He left Australia on the troopship Euripides on May 8. He served at Gallipoli from September until the evacuation and was killed at Pozieres, France, on August 24, 1916. He was acting in the rank of Sergeant at the time.

Herbert Henry “Bert” enlisted in March 1915, aged 18, leaving Australia on the Wandilla on June 17. He joined his combat unit at Gallipoli on August 6, 1915, suffered gunshot wounds to the abdomen the following day during the Lone Pine battle and was buried at sea from the ship Dunluce Castle between Imbros and Mudros. Neither Burvett nor his other son, Alfred Jnr, knew of Herbert’s death until October that year.

Burvett’s pianist sister Alice Sydney died in June 1919.

His eldest daughter Clarice drowned in the surf at Lorne on February 7, 1922, having attained her majority a few weeks before, on January 27. The Horsham Times of February 14 reported that Miss Burvett had gone to Lorne with her youngest sister (10-year-old Dorothy) and a friend, having pleaded with their father to let them go. Burvett had wanted them to holiday somewhere else, but gave in to their pleading. Clarice, Dorothy and their friend Massie Holliday went swimming with another young woman and three men opposite the Lorne Tennis Club at 11.30 in the morning. They were caught in an undertow that swept then into an offshore channel. Five got back to shore, but Clarice and Massie became exhausted by the effort. A 58-year-old Geelong stockbroker, Samuel Michael, managed to catch hold of Miss Holliday and drag her close to the beach, but then had to let her go, himself collapsing from exhaustion. Other people completed Miss Holliday’s rescue, but Miss Burvett could no longer be seen. Victoria’s champion lady swimmer, Miss Lily Beaurepaire, heard the cries and dived into the surf and swam out in search of the missing girl, with no success. The body was found soon after, about 2km from the spot where the swimmers entered the water. When Burvett heard the news, he was “doing business in a leading Melbourne solicitor’s office, and at once caught the Port Fairy Express”. Clarice’s body was brought back to the family home at 3 McKenzie Street, Melbourne, for burial.

Just 15 months later, on October 3, 1923, Burvett’s second daughter, Irene, died in extraordinary circumstances at the home she shared with her father. Aged 15 years and nine months, she shot herself with her father’s revolver. Burvett gave evidence at the inquest that he usually kept his revolver locked in his desk. He believed his daughter must have unlocked the drawer and taken the revolver out.

Witness Beatrice Dillon, who lived in a flat above the Burvetts and had been in the Burvetts’ kitchen, preparing a meal with Irene, said she overheard the girl talking on the telephone, complaining about her father’s efforts to prevent her from going out dancing. She had told the person on the other end of the line that she was going, despite her father’s insistence that she remain at home. Burvett said he also heard the conversation and concluded that his daughter was planning to go out against his wishes. She told him she had forgotten to pick up butter and asked for money to go out and buy some. He replied that he would buy it himself. Immediately afterwards, Irene had gone upstairs and the shot was heard. He said he rushed upstairs, saw his daughter on the floor with a bullet-wound behind her right ear and called out, prompting Mrs Dillon to also run upstairs. The revolver was found on the mantelpiece. Burvett suggested that his daughter, whom he described as “brilliant, if a little headstrong” must have been gesturing with the gun for dramatic effect and that it must have gone off accidentally. He suggested the gun must have fallen onto the mantelpiece as Irene fell to the floor. Asked if his daughter resented his efforts to control her, he said: “She had no occasion to do so. But we had told her we did not like her going out dancing so much.” The coroner’s verdict was accidental death from a self-inflicted bullet-wound.

In 1930 Burvett’s remaining son, Reginald Stephen, the well-paid chief clerk of BHP’s Sydney office, was charged by police with attempted to pick pockets at a housie game at Manly Venetian Carnival. He was arrested on January 17 when police inspector Alfred Winter had Burvett pointed out to him by a young man. Burvett was standing close behind a man, pressing against him. The man moved away, then Burvett took up a similar position behind another man. He was closely watched and allegedly kept positioning himself behind men. The police testified that Burvett ran his hands over the men’s pockets, and also allegedly tried to lift a tray from a chocolate vendor.

For his part, Burvett claimed the police repeatedly called him George, and suggested he had previously been fingerprinted and spent time in jail. Neither suggestion was true. He also testified that the police had tried to persuade one of the boys from whom they alleged he had tried to steal, to say that he had lost a roll of notes. Burvett’s lawyer argued that his client had worked for BHP since 1913, was highly paid and had excellent references. He was acquitted.

Reginald died in Newcastle Hospital on December 27, 1941, leaving Dorothy – then aged 43 – as the only survivor of the family. Reginald would have been aged in his early 40s at the time of his death.

.