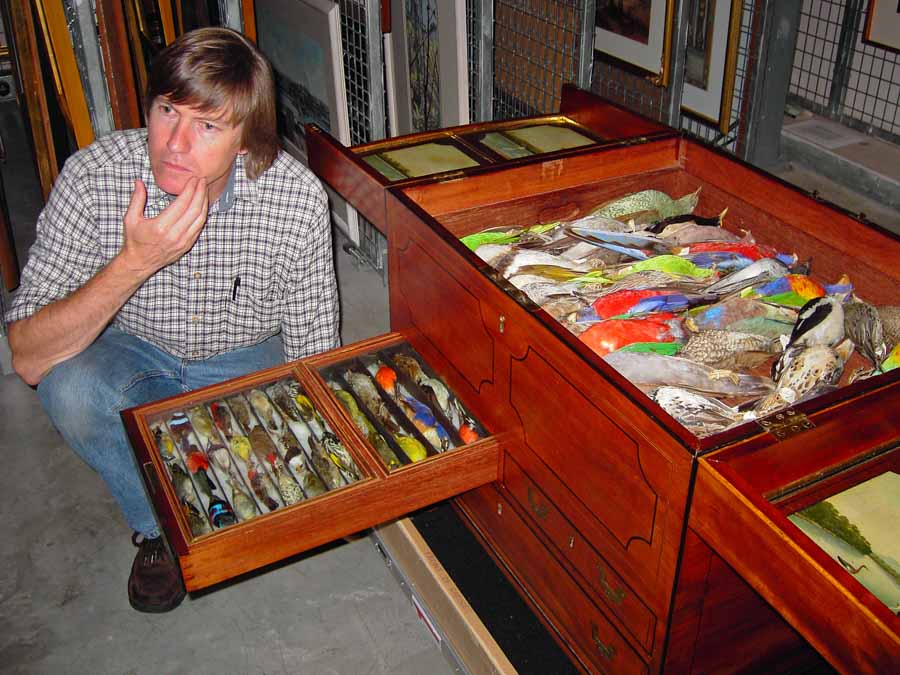

THE feathers of the birds lying side by side in the box seem almost as fresh and bright as if they’d been trapped yesterday, rather than preserved with arsenic two centuries ago. There are about 80 of them: a tawny frogmouth, a vivid kingfisher, parrots, a regent bowerbird and many more.

.

Seashells, arranged in geometric patterns by an unknown hand on the strange, wild shores of a new-found country, gleam in their drawers as though just gathered from the beach. Every drawer in this plain-looking wooden chest reveals peculiar treasures: carefully preserved birds, butterflies, beetles, insects, spiders and seaweed.

And on the inside panels of the mysterious artefact are beautiful, bright paintings some of which depict the scenery around Newcastle and Lake Macquarie in the early years of European settlement.

.

Since the 1970s when Australian historians and art lovers first learned of the existence of this strange “collector’s chest” in a castle in Scotland where it had sat for more than 150 years, they struggled to piece together its story. Now in the ownership of the State Library of NSW, the chest has slowly revealed many of its secrets.

.

One of the few things considered to be relatively certain is that the piece once belonged to the former governor of NSW, Lachlan Macquarie, who took it with him when he left Australia under a cloud in 1822, criticised by the British Government for spending too much money and trying to turn a no-account criminal settlement into something resembling a civilised place to live. It is widely believed to have been a gift from the commandant of Newcastle, Captain James Wallis, who was a protege of Macquarie. Macquarie is known to have had a soft spot for Newcastle, where on his orders a stone church, a decent breakwater and numerous other public works were built.

The theory is that Wallis had the box made in about 1818 by convict cabinet-maker William Temple. It is believed that the paintings inside the rosewood and cedar box are the work of convict artist Joseph Lycett, who painted a number of famous scenes of the Newcastle area and is also credited with helping in the design of the settlement’s first stone church. This church appears in some of the chest’s painted panels.

Elizabeth Ellis, of the Mitchell Library at the State Library of NSW, wrote a book, Rare and Curious, on the so-called “Macquarie Chest”. She told me, when I interviewed her in 2006, that the library had bought the chest in 2004 from a private collector who had acquired it in 1989 when it was auctioned in England. Ms Ellis, who treated Sylvia and I to a private viewing, described the $1.2 million purchase as one of the library’s most significant buys of this generation.

.

Actually, she was present at the 1989 auction in Melbourne and saw it go under the hammer to a Sydney buyer. Ms Ellis made contact with the new owner and stayed in touch for 15 years when it suddenly became available to the Mitchell Library.

It seems the chest had found its way to Strathallan Castle, in Scotland, when Macquarie’s only son, Lachlan Jnr – often described as “a wastrel” with alcohol and gambling problems – met his end in a drunken fall and most of his late father’s estates and possessions were used to satisfy his debts.

Interestingly, the Macquarie chest has a twin: a similar, better made but less pristine chest which is also in the State Library. This chest contains only remnants of biological specimens and has been modified.

Historian John McPhee, an expert on Joseph Lycett, believes this chest was made earlier than Macquarie’s, possibly in India. Mr McPhee’s theory is that James Wallis had probably acquired the first chest and taken it to Newcastle when he became commandant. He may have had it copied by convicts, using materials at hand, as a gift to his patron Macquarie.

Elizabeth Ellis elaborates:

Concealed inside the chest’s austere exterior are a sequence of painted panels, hidden drawers and layers of exotic natural history specimens which may be gradually opened out to display gorgeous, brilliantly hued arrays. When all the panels and drawers are fully unveiled, they evoke for the contemporary viewer the same sense of breathtaking wonder and delight experienced by early European visitors on first encountering Australian fauna and flora.

.

The contents of the chest consist of natural history specimens and, apart from the lower front drawer, appear to be more or less intact. The arrays of specimens are quite astonishing in their freshness and state of preservation. Inside the top compartment are four glass-topped boxes, edged with gilded and cedar banding, which contain collections of NSW specimens of butterflies, beetles, insects and spiders, presented in decorative arrangements.

Beneath the removable painted panels in the concealed side drawers are seaweed and algae specimens, and in the two trays of the centre compartment are 45 stuffed birds of Australian species, including a tawny frogmouth, satin bowerbird, regent bowerbird, and a variety of kingfishers, parrots and herons.

.

One of the two smaller drawers in the front of the cabinet contains two glass-topped boxes with another 35 smaller ornithological specimens such as wrens, robins, honeyeaters, finches, firetails and pardalotes. Most of the birds retain their original handwritten tags, numbered to refer to a list of contents which is no longer extant. All the birds were found in the Sydney and Newcastle regions in the early 19th century. Some have subsequently become scarce or rare because of urban development, reduction of habitat and the introduction of predators.

The lower right-hand drawer contains two boxes of shells, one of larger specimens, the other smaller. These retain their original gilded dividers, forming geometric star-like patterns. The arrangements do not appear to be attempting any scientific order, but rather an appealing decorative display.

.

The original collectors and taxidermists, whose work has survived so well, are unidentified.

The single lowest drawer, extending across the width of the case, contains a miscellany of items which are only a portion of the original contents. These include Solomon Islands artefacts, toucan bills from Central America, dried Pacific Ocean flying gurnard (fish) and other unrelated items of memorabilia.

One of the most striking features of the chest are the painted panels which appear once the top lids are opened up.

.

One set of panels depicts pairs of birds (black swans, royal spoonbills, brolgas, a native duck and cotton pygmy goose, egrets and pelicans, a galah and crested pigeon) which are or were commonly found in the Lower Hunter.

All the backgrounds of these bird paintings can be identified as locations in or around Newcastle and Lake Macquarie. Three include buildings of the Newcastle settlement as it might have appeared in 1818.

More information about the chest and its history can be found here and here and a video about the chest can be watched here.

.