IN late 1942, Australia was committed to total war in the Pacific. Its economy was practically 100 per cent geared to war production and “manpower” was a critical problem. A country with a relatively small population, it was isolated from accustomed imports, had large numbers of men fighting or in enemy captivity overseas and was struggling to boost industrial production.

More and more men were drawn from their pre-war occupations and put into uniform, leaving big gaps in the industries from which they had been taken. The government turned to Australia’s women for part of the answer, establishing a Women’s Employment Board to advise on how best to utilise this large pool of labour to help harvest crops, provide support to the military establishment and to take over from men in factories and in public service roles.

For many women this proved to be a truly liberating experience. Many found purpose, independence, camaraderie and confidence in their new – often well-paid roles. Sometimes male-dominated trade unions expressed unease about women moving into jobs that had been exclusively held by men, and when the war ended many women were decidedly unwilling to relinquish their temporary wartime positions.

Among the jobs women were permitted by the Women’s Employment Board to occupy were roles as bus and tram conductors (or “conductresses”, as they were known). This was not unprecedented in Australia: in 1918 three conductresses were licensed in Sydney, on the city to Burwood run. In late 1942 it was reported that about 900 women were employed in public transport services in Melbourne and about 250 on trams and buses in Sydney, where they were being hired at the rate of about 25 a week. At the time, the buses and tramways were critically important services. Few people owned cars and in wartime petrol, tyres and other motoring necessities were practically unobtainable. To keep the industries going, people had to get to and from work – at the very least.

In Newcastle a first intake of 20 bus conductresses started work on January 4, earning the minimum male wage of £3 and six shillings a week. It was not considered possible to have female tram conductors in Newcastle, since the city’s trams lacked internal corridors – unlike those in Sydney – and it was deemed unsafe for women to risk clambering around on the outside of the tramcars, as male conductors did. The women were employed on the strict understanding that their jobs would last for the duration of the war or “until manpower is available”. The opposition of the male-dominated Bus and Tramways Employees Union was set aside in return for a promise that, if the women were employed, the remaining men in the transport services would have some much-needed relief from severe workloads. It was reported that most had been working “14 shifts a period with excessive hours”. Since the war began in 1939 no holidays had been permitted. To make the men accept female co-workers they were promised fewer hours and their day off each week. The men agreed to accept the arrangement until all accumulated long-service leave and public and annual holidays were cleared.

At their briefing on January 1, 1943, 19 of the first 20 Newcastle conductresses (one was off sick) were told to always be punctual and to avoid arguments with the public wherever possible. District Superintendent Kilpatrick warned them that “the public, as a body, was rather unsatisfactory to deal with, but individual members would be found generous and considerate”. The women would “have to submit to many complaints, sometimes justified but often unwarranted. To treat these with patience and courtesy would avoid their having to write reports.”

Asked by a reporter why she had applied for the job, one woman said she had two brothers in the Army and wanted to do her bit. Another said “the life appealed to her”. Asked whether she though the job might become boring, one answered that it could not possibly be more boring than housework.

It was stipulated, among other things, that applicants for the jobs be no shorter than 5ft 3in “in low-heeled shoes”, and there was evidently some controversy when women who didn’t apply because they were shorter than the limit later saw conductresses even shorter than themselves working on the buses. One unhappy correspondent to The Newcastle Herald asked how this could be, but the District Superintendent of Transport, Mr Kilpatrick, declined to comment.

In those days, bus drivers were considered to have enough to do already without collecting fares, so this was the job of the conductor. It was all cash, of course, and was no simple matter, since fares were calculated according to sections, and different charges applied to adults, children and weekly ticket holders. The right money had to be collected, tickets punched in the correct places and some semblance of order kept aboard the often crowded vehicles. Asked how they liked the job after a month or two, conductresses said they liked dealing with workmen – especially miners – who were always courteous and had the correct money ready or were willing to help ensure their tickets were punched in the right place.

According to a news report: “On the long runs to the lake where 14 and sometimes 29 sections intervened, the girls needed all their wits to keep in touch with the various fares”. One of the hardest things had been getting their “bus legs”. To begin with they often “staggered into seats and almost sat in the laps of passengers when they had no intention of doing it”. But after a while they learned to “sway with the bent-knee action of good sailors” and could “ride the corners with ease”.

In an article in The Newcastle Sun on June 24, 1980, former conductress Elizabeth Alder described the job: “At one stage I had to work 28 days straight. We didn’t think to protest. Everyone was doing their utmost for the war effort.” At one point a mass meeting of transport employees (probably in Sydney) was told that conductresses were sometimes obliged to sleep on buses or at the depot because the department did not provide them with transport home when their shifts ended. They were also often abused by passengers who insisted on forcing their way onto already overcrowded buses.

Mostly the women took the challenges of the job in their stride and soon won the respect of the drivers and the public alike. They were regarded as especially considerate of mothers and the elderly, making sure they were seated and their bags and parcels looked after.

Conductresses were also employed by the operators of a number of private bus services during the war years. The late Ken Magor interviewed former conductress Mrs Pat Hazell, who had worked for Menson’s bus service – along with colleague Norma Harvey – in the Merewether area between October 1942 and about March 1945. Before starting work as a conductress, Pat had driven a five tonne truck. She said the buses were often extremely overcrowded and once, when she had blown her whistle for a packed bus to leave a stop, she found she had no room to step aboard and was left behind. She said children routinely claimed to have lost their penny fares, often telling this tale with chocolate on their faces.

By the time the war ended many of the women were resigned to leave their jobs as conductresses, but quite a number were keen to keep their jobs, for the working lifestyle, the money or both. Interestingly, elements in the same union that had opposed their employment were now inclined to argue for their retention, although this sentiment was not necessarily shared by all male union members, some of whom saw the women as an obstacle to them regaining their former jobs.

Interviewed by The Newcastle Sun in February 1946, one former conductress said she had been afraid on her first trip to ask for fares, but after years on the job was able to “persuade a drunk off the bus without turning a hair”. Newcastle’s first conductress, Lilian Mathews, said she had worked in a textile factory before the war but could no longer go back to a job like that. “I want to be out in the open,” she said. Those who finished up had five to six weeks of paid leave owing, plus a free railway pass. Some planned to take a holiday, but others with family responsibilities were under pressure to find another job as soon as they could. Most had finished up earning between £6 and 5 shillings and £7 and five shillings a week, with penalty rates, and it was practically impossible to match that pay in other available lines of work.

Betty Hitchen, of New Lambton, told a reporter that she would miss the companionship but appreciate not having to get out of bed at 3am. She said many regular passengers had told her they would miss the conductresses, but others said they were glad to see the women going back to their “right job” – scrubbing floors. The Newcastle Herald editorialised that the women needed to stand aside to allow men to have jobs, noting there were plenty of vacancies in other areas such as hospitals and factories. “No doubt women will maintain their place in many callings they entered during the war, but the vocation of matrimony will remain supreme, and its economic basis is full employment for husbands and fathers,” the newspaper concluded.

The lack of any formal thanks from the Transport Department rankled strongly with the women, who felt they deserved at least that after all their effort. One correspondent to The Herald, however, disgreed. Writing under the pen-name “Key Hole”, this female worker who had spent the war years in a factory argued that the conductresses did not deserve any special bouquets. “The bouquet-throwers should visit the industries where women really did a man’s job,” she wrote. “I am 48 years of age and handled, formed and re-handled, bent, sorted and checked anything from 25 to 35 cwt of keyhole ties every eight hour shift – and I don’t mean the keyhole you place a key in. Bouquet-throwers, save work and expense by forgetting the bus conductresses as thousands of other women who did war jobs are forgotten”.

The fight to keep their jobs was fought hardest by conductresses in Sydney who managed to force their union to agree to a special meeting to discuss the issue and also pressed for the rescission of a pre-war motion objecting to their employment on trams. The proposed meeting lapsed for lack of a quorum, prompting the women to accuse the union of “selling them out”. An unnamed union official told a reporter that “the protest against the women’s retrenchment is being supported by the Communist Party. It is not a career job for women, who are obliged to rise at 2.30am on morning shifts and knock off in the early hours of the morning on night shifts”.

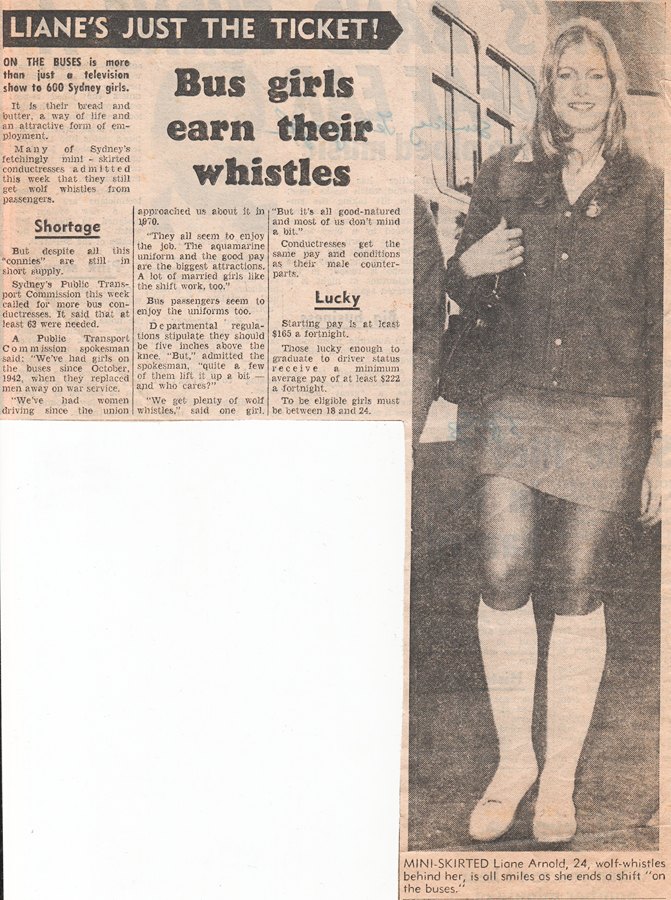

It seems that, ultimately, some of the most persistent women managed to be re-employed as early as late 1946 in Sydney, with some remaining in the jobs for decades. In October 1972 The Sun Herald reported that one of the original wartime conductresses, Mona Faggney of Neutral Bay, was still on the job. She was the last of the old guard, but many more had since been employed. In 1973 there were said to be 600 conductresses employed in Sydney – now with mini-skirts as part of their uniform. The department was trying to recruit more.

In the 21st century in Australia bus conductors of either gender are a thing of the past.

Conductresses on the buses: the last conductress on the right of the top row in the group photo, and on the far left in the wedding photo is Nancy Leigh (not Leahy). She was my grandmother Emily McGregor’s niece. I remember seeing her on the bus as a small child.