During World War 2, when most able-bodied males were either overseas fighting, or working in essential industries, women were recruited for many roles that had previously been men-only.

Newcastle’s heavy industries made it a vital part of Australia’s continuing war effort, so its defence was critical. That was a primary reason for the establishment of the Williamtown fighter base, and it was also why large numbers of women were put to work in many defence-related jobs around the region.

The Australian Women’s Army Service was formed in August 1941 and in two years its numbers had grown to 25,000. The first AWAS in Newcastle served at Fort Scratchley, operating searchlights and other equipment. Others worked at Fort Wallace (Stockton) and at “Wipers”, an isolated radar station north of Stockton, access via Cox’s Lane. Some also worked at a gun emplacement near the industries at Mayfield and a gun operations room at Lambton.

Unknown to many people at the time, the night skies above Newcastle were regularly invaded by high-flying Japanese reconnaissance aircraft, seeking information that might be useful in any future attacks. Edna Petfield (nee Selwood), whom I interviewed in 2008, was a member of the AWAS, in the 51st Searchlight Battery with a headquarters at School Hill, halfway between Williamtown and Nelson Bay.

Working 12-hour shifts, six days a week, Edna plotted the courses of the intruder planes. Reporting to her operations room were eight searchlight stations north of the Hunter River, and another eight on the south. One was on Glebe Hill, Merewether, one was near the Wallsend brickworks, another was near the Murray Dwyer orphanage at Mayfield. Others were at Fullerton Cove, Beresfield, Stockton, Tomago and in the Raymond Terrace cemetery.

The women on the searchlights were chosen for good eyesight and hearing, and were trained to identify different aircraft types.

“We always knew which were the enemy,” Edna said. “Our own planes always flew along allocated lanes and every day there was a new password.” The enemy planes came in from sea, very high, swung in a wide arc around Newcastle they flew out to sea again.

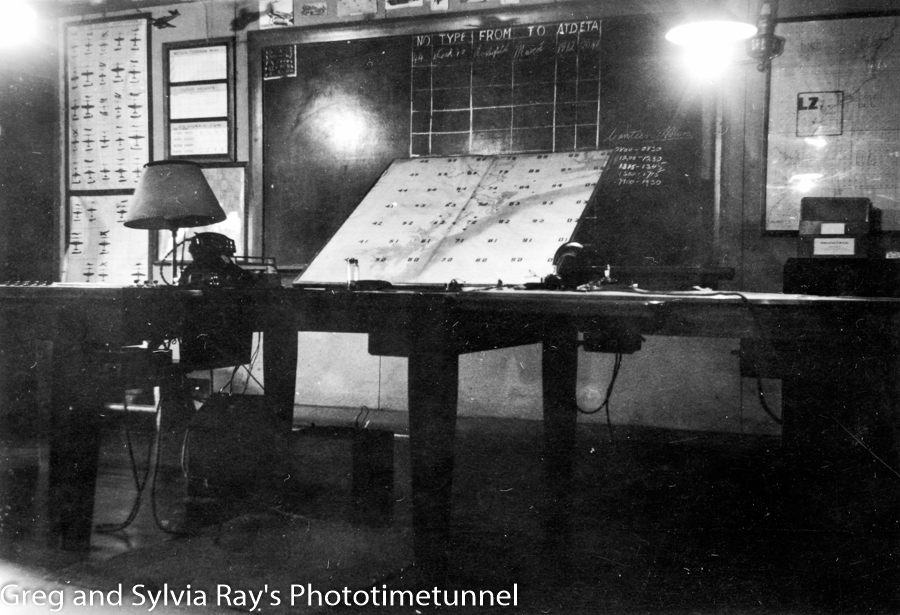

Photo by Edna Petfield.

The searchlight operators never turned their lights on the enemy planes: that would only have betrayed their positions. Instead, they used special direction-finding equipment, phoning in their estimates of the planes’ positions to the operations room where they were plotted on map tables. The only was usually only used on practice subjects, like the nightly mail plane that few between Sydney and Brisbane.

Life in the searchlight batteries could be rough and ready. The girls slept in unlined sheds in the bush, with mattresses made of hessian bags stuffed with straw. Their shower was a kerosene tin with holes in the bottom, hung from a tree. There were long training marches with full packs, and training (at Adamstown rifle range) in the use of rifles and machine guns. On their one day off each week a truck would take them to Stockton where they would catch the ferry to Newcastle.

Searchlight girls at Adamstown.

Searchlight girls at Adamstown.

Searchlight girls on a .303 shoot day.

Edna Petfield (left) and her friend Mac.

Searchlight girls.

Bren training at Adamstown rifle range.

“Where the old Johns building used to be there was a leave house where we could have hot showers, real beds and a bit of mothering from the wonderful women who ran the place,” Edna said. By 9pm it was time to catch the ferry back, so there wasn’t much time for dances or movies.

When the tide of war turned against the Japanese the spy-flights finished and the searchlights were packed onto trains near the Zaara Street power station and sent away. After that happened, Edna was sent to Sydney to work as a finance clerk, reconciling the damaged paybooks of soldiers.