Among some papers given to me by Barry Magor – son of transport collector Ken Magor – was a photocopied pamphlet titled: Memories of the Hunter and Newcastle in the Eighties, by Audley Reay. That name was unfamiliar to me, until I spent a morning interviewing centenarian Neville Chant, who unexpectedly brought up the same unusual name in the course of discussion, describing Audley Reay as Maitland Council’s health inspector who once lived – according to Neville – “next-door to the pigyards”.

A search of Trove reveals that Mr Reay was the son of Robert Reay, who came to Morpeth from England in about 1860 and had a number of businesses before running a hotel in Hunter Street, Newcastle. Audley Reay worked for Newcastle Council in 1905, at the time of a plague outbreak in the city. Most of the rest of his career was spent in Maitland, where he had a reputation as a stickler for the rules ensuring the purity of meat and milk, and also for minimising infectious diseases by helping get rid of old-fashioned cess-pits and promoting modern sewerage schemes. He was also a noted horse racing enthusiast and had a strong interest in other sports including cycling, running and sculling. He married Lila Logan, of Maitland, in 1919. He retired in 1939.

His book – a slim volume of 31 pages – is full of interesting recollections. I’ve transcribed the entire work, below. On the flyleaf is the following handwritten inscription: “Printed at a time of great shortage of labour and materials. Many errors and omissions. Two first pages left out. A plain brief picture of the times. Historical.”

.

.

A sea-bird screams and echoes start, From Nobbys tunnels far away. It finds an echo in my heart, And tells a tale of joy’s decay. (Coolgardie, 1893)

(The tunnels, I understand, are now blocked. They were a favourite “pirate’s lair” for boys in the eighties.) Audley Reay

.

In the time of the wind-jammers

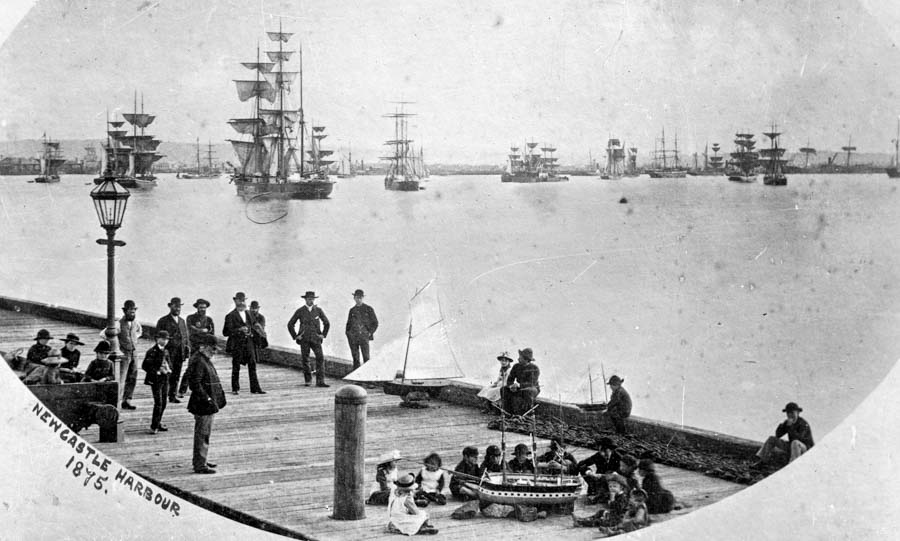

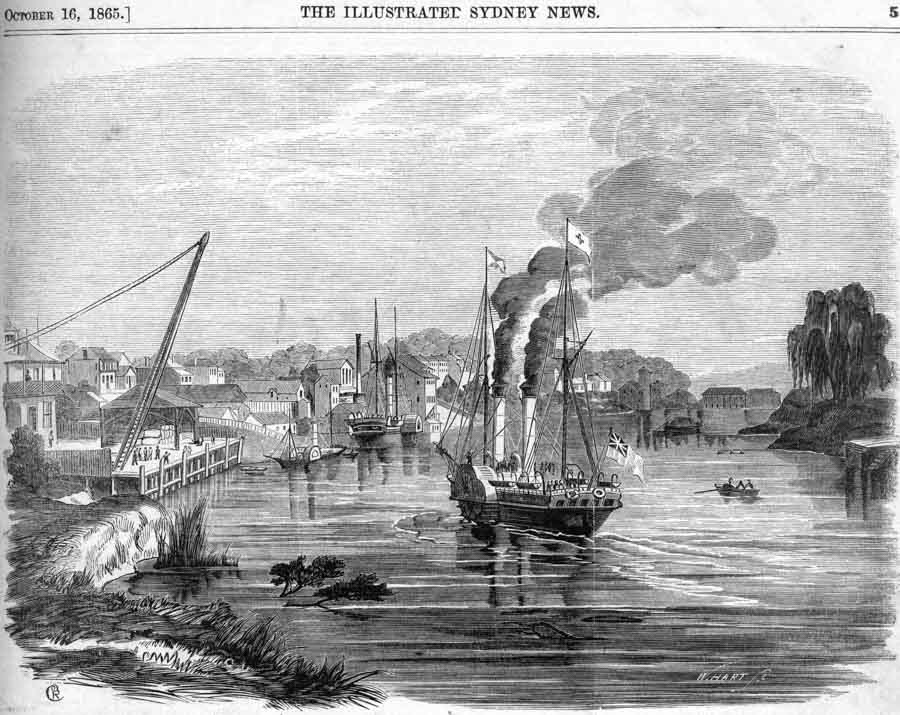

It was the time of the wind-jammers and Newcastle was a very busy sea port. The wharf from the custom house to the pilot station was the main coal-loading wharf with steam cranes-whilst the Dyke had eleven hydraulic cranes managed, in .conjunction with the railways. Scott Street was the hub of the shipping world and footpaths were non-existent from Newcomen Street to Market St.

Inspector Lynch was in charge of the police – a very courteous and efficient officer. He arrived in Australia about 1854 (a guess) in the Annie Wilson, a sailing ship. The author’s mother was also a passenger in the same vessel.

Sergeant Finnigan was the most prominent policeman. H. J. Brown was Council’s Solicitor. William Sparke was regarded, even in those days, as an outstanding lawyer.

Hotelkeepers Messrs Watt, Great Northern; Lindsay, Crystal Palace; Buchanan, Criterion; Fraser, The Exchange, were outstanding citizens. Harry Stegga’s store and the home of Father Peters of the R.C. Church, were on portion of what is now Scott Street, near Market Street gates – this spot and the railway gates at Newcomen Street (since closed) were the two main means of access to wharves. Gatekeepers opened them by hand. The railway to Sydney had not then been built so that everything came from Sydney by boat. At first there was only the Kembla.

Hartley Spurr opened a shop near the Stockton Ferry, supplying fish and bait. The old boat harbour was a busy place with the large number of watermen and their beautifully built watermen’s skiffs – mostly cedar-built by Towns. Produce was brought by pulling boats down the river and in the melon season, with other youngsters, we would help to unload them. We would get nothing for our trouble unless a melon was broken, so that it can be understood we soon woke up and saw that we had a feed of watermelon. Mr. Woodcock had a large fruit shop and used to cart bananas. It was great fun for the kids to pretend to try to “nick” some of the fruit; his reaction was good.

Clarence Hannell was shipping master. He had a great reputation as a fisherman. Our greatest fisherman was David Thom, a draper, who kept a shop two doors from Newcomen Street in Hunter Street. He would often take me out with him and he would fish always in the one spot – out in the stream where the vessels were loaded ready for sea. When the sailing vessels were loaded they would be towed to the “stream” and await favourable wind, crew etc. Thom was never known to return without a heavy string of whiting and flathead. Mr Hannell was jealous of Thom, but I so often saw their catches that I can vouch that he was not in the same class as Thom, who was a wizard.

The Church of England, Dean Selwyn, was at the same spot as the Cathedral. The R. C. Church and Convent were situated as now. Father O’Gorman was best known to school kids whom he used to chase with a stick. The Methodist Church was in Tyrrell Street, near the old Hill School, Rev. Charles White, Brown St., Congregational. The Hill School; which turned out many good men, had Charley Friend as headmaster; he established the school cadets whose uniform was grey trousers, blue serge coat with red trimmings and a peaked cap haying a trumpet as an ornament in front. The rifles were muzzle-loading Enfields (used in the Indian Mutiny) and smooth bore rifles for the small boys. During the time I was in them a party of Japanese midshipmen visited us -included were some men who later became famous – one Admiral Togo who figured prominently in the war with Russia. There was a public school in Bolton St, the head teacher, for a time, being Mr Southwell.

Commander Gardner was head of the fire brigades and also the Naval Brigade, of which the late Jimmy Wiggins was a prominent member. Their headquarters were in Newcomen Street. The corner block opposite “Coo-ee” store in Newcomen and Hunter Streets was vacant and it was here all the various sideshows were seen: a big local show consisted of Joe Harman, boxer and club-swinger; Mick Huntsdale, who used to pass through a very small iron ring; Dickey Pattison, Newcastle’s wonder-athlete, and strong men of whom I shall write later. The spruiker would tell the crowd “each and every man a star in own particular line – men who have travelled the world and never found their equal”. “A variety show and a boxing booth.” George Mulvey, the basket-maker, lived opposite and a very nice lady of large proportions had a lock-up shop entitled “The Little Wonder”.

J & A Brown and Dalton were the principal tugboat owners. Callen’s slip at Stockton was always busy with sailing vessels being overhauled. At times along the Stockton foreshore there would be a forest of masts, the vessels being moored two and three abreast. Amongst the windjammers I remember were the Briar Holme, a most beautiful barque built of steel for the Paris Exhibition – all her brasswork was half-inch brass. She was built to carry passengers, though I do not know if she ever carried any. She had two pianos and an organ in the saloon. This beautiful vessel was lost later and an account of her wreck is given herein. The barque Saxon: Captain Bunker, the mate was Hopkinson. This old wooden tub came from Port Pirie to Newcastle in eight days, breaking the then record for a sailer. The captain was not well and, taking to his cabin as he left Port Pirie, let Hopkinson drive the ship through in record time. He later became master of the Saxon and he gathered round hm a wonderful crew whom he had made like himself – well-dressed, sober respectable men. This at a time when most sailors spent their time ashore in drinking.

The Remijo, reputed to have previously been a man-o-war – her wooden sides were said to be six feet thick. The La France, six-masted ship, was the largest sailing ship in the world at the time. The Simla was another six-master, I think, and she in her day was the largest afloat. The Simla sprung a leak in the English Channel and was abandoned. Several days later she was picked up and towed to port. That trim little ship the Cutty Sark used to unload at the Queen’s (now King’s) Wharf as did several other clippers which would later unload wool near the pilot station and sail for London direct. In the off-season the large wool-dumping sheds were used as a skating rink. The powder magazine was anchored near the pilot station and the self-righting lifeboat – afterwards used by the Rev Mr James of St Mark’s Islington, after he had established the Seamans’ Mission.

James Clark was the ship chandler in Scott Street between Market and Newcomen Streets. His store was destroyed by fire. There were some big fires, notably one where Scott’s store is today. For about halfway to Wolfe Street the buildings were destroyed. The block occupied by Stegga’s and others, extending to Breckenridge’s was a bad fire, accentuated by the roofs being of shingle covered with iron and the difficulty of removing the iron to get at the flames.

Mr Barnett, father of Sam, kept a grocery store at the corner of Market and Hunter Streets. He had a half-crown nailed to the counter and most of his customers would try to lift it when he wasn’t looking. Sam Field and Thomson and Johns were the principal shipping butchers. Their agents were watermen who raced to the incoming ships – the first to reach her would get the trade during the time she was in port. These boats were, I think, about 27 feet long. They were fitted to be rowed by four men, but it was the usual custom; as they found the trim more satisfactory, for three men to operate them – the vacant seat being nearest the stern. This kept the bows down and the stern high. The Hickeys, Hughes, Trevelan were names that will not soon be forgotten by old timers. They were supermen in every sense of the word – I have known them race to a ship off Redhead, hammer and tongs all the way. To anyone who knows anything of sculling, the real merit, extraordinary as it was, lay in the fact that these men used a style of sculling rarely seen outside a racing shell, viz., the weight was on the commencement of the stroke. On Regatta Days to see the ”Butcher” Boat Race, twice around a course from Pilot Station to end of Dyke, was an aquatic treat – no slackening but top speed over this strenuous course, and the competitors finishing brilliantly. Yes, they were supermen.

The flagship on New Year’s Day Regatta was always a fine full-rigged sailing ship. The wharves were crowded with people, side shows, refreshment booths. Some of the lads could always be depended upon to catch a giant sunfish or a big shark to exhibit, while the tugboats would take full loads of passengers “all round the harbour for a bob.”

The western half of what was known as the inner harbour, where the grain elevators are, with the exception of a small channel about three feet deep for pulling boats, was often waded across by the kids -that would be about the end of’ western wool store. A man with a waterman’s skiff ran a penny ferry from Howard Smith’s wharf to the end of the Dyke. We used to bathe “behind the hospital” (now Newcastle Beach) in the nude until 8 am. Sergeant Dick, father of “Billy”· (MLA and one time Acting Premier), George and Charlie, shipping agents, was the leader of the morning surfers. He was a very fine man and kind to us youngsters.

Many vessels were lost

Many vessels carrying coal to the West Coast were lost. It was due, so they said, to the coal cargoes generating gas and causing spontaneous combustion. Of course, as a matter of fact, many vessels were deliberately lost in order that the insurance could be collected. I well remember one poor woman whose husband had gone down in a rotten tub owned by a certain ship owner, whose vessels – at least all I saw – should never have been allowed to go to sea. She approached the owner for some assistance. She received the answer: “What was your loss to mine?”Those days of lack of supervision and the “open go” are happily gone, and vessels today are usually well found and fit for sea. It was common to see a ship arrive with a cargo of coconuts as ballast whilst many arriving from “the Islands” would invariably have huge bunches of bananas suspended from the jib-boom. On steamers from Manilla a large bundle of cigars could be bought from the sailors for a shilling.

We saw the habits of Hindus, Chinese and Malay seamen at meals, pastimes and gambling. The Chinese with the opium smoking, their meals of rice and fish, the smart little midshipmen from the clippers of Holme Line (Myrtle Holme, Briar Holme, and others), the White Star Line, The Black Ball Line and others all helped to make interesting sights along the waterfront. The “Middies” were well-dressed in blue uniform with brass buttons and cap and were very smart.

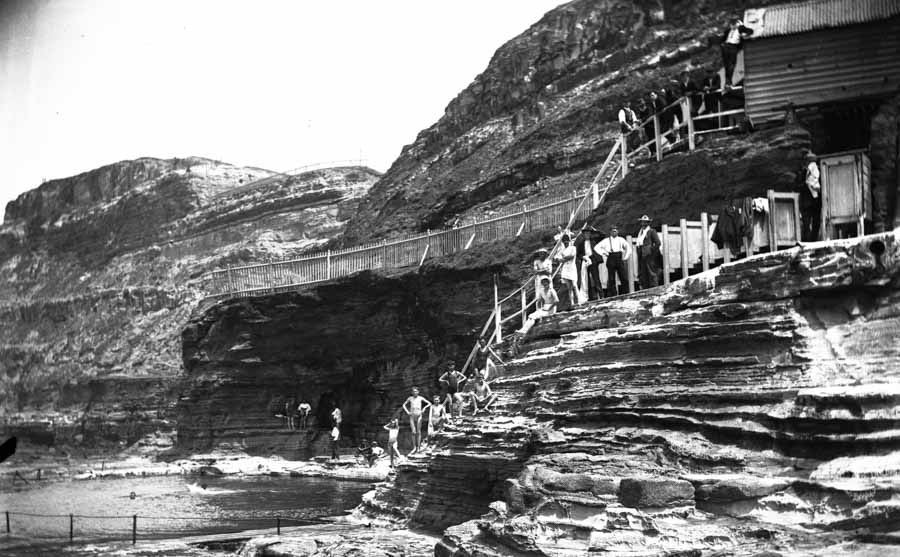

The Soldiers’ Baths were constructed, simply a half-circle of rocks to prevent undertow and keep out sharks, below the forts. A heavy storm destroyed most of it, broke the planking running into the deep water and damaged the dressing sheds. Despite this it was a favourite swimming place for many years, though the silting later was troublesome. There was also a small swimming hole near where the present Ocean Baths are, this was almost silted up with sand but was useful for children. The Bogey Hole was always the best place for a dip, but dangerous in bad weather. When the tide was very high and weather rough it was a most delightful place if you could get safely in and out. To a moderate or indifferent swimmer it was hard to get out without a few scratches from the rocks. There was a narrow path round past the Bogey Hole to the wreck of the Newcastle – the remains of her boilers and engines were still visible. The reef and the Gulf nearby were greatly favoured swimming spots. To swim from the reef to the Gulf stamped a school boy a hero, but it was necessary for every boy to swim in the Gulf at least once. There was, of course, no danger but as one had to wait until a wave came high enough to lift him onto the landing rock, some would wonder if they would ever make it – of course l am speaking of youngsters 10 and 12 years of age. Another stunt the boys of the old Hill school used to get up to, viz., climbing up the cliffs from below the house at top of High St. The writer did it as a very small boy. There was no danger, but once you started there was no going back, and the tufts of grass one held onto had to be treated very gently or they would come out by the roots.

The sand drift used to spread across Lake Road (Darby St.) and upon one occasion one of Bobby Dailey’s two-decker buses was blown over by the wind in the same Street.

Old Bill Treacy was caretaker of the Cricket Ground whereon we saw W.G. Grace play.

Very large boats, propelled with oars, used to bring lime from Stockton. The Saucy Jack was the best-known ferry.

“Buffalo Jim”, known as “Big Jim” or “Big Jim all the same” was cock of the walk for years in Scott Street. He had been a ship’s boatswain, a tough job in those days. He was a huge shaggy man, not unlike a buffalo in appearance, but dissipation had wasted his powers until another “Big Jim”, a very sober, clean living man, came along. They were both boarding house runners. They met in Newcomen Street, and the writer saw that fight. The old battler did his best, but youth must be served and gradually the old man weakened and the new “Big Jim” was proclaimed the winner.

The tram terminus was at Perkin St. After unloading the trams would back into the railway premises – this was a very dangerous practice and amongst those killed by the tram backing was a young man named Beecham, he was a seaman on the steamer Birksgate. He had received a good education and was just about to sit for his Master’s Certificate He was fond of deepwater, often trading to the West Coast and the Rio Grande in sailing ships. I used to like seeing him moving about the rigging of a ship. He was only twenty-three.

The Fanny Fisher was a very small barque trading to Sydney, the Mary Wadley, a three-masted schooner trading to Napier, with her Captain with his fiery red hair and fiery temper.

R. B. Wallace was one of the principal shipping agents, whilst Dalgety seemed to handle most of the wool. H. R. Cheek was a colourful personality. In retaliation for practical joking he had a successful law suit that rocked Newcastle and ruined his opponent, who occupied many important positions. The loser shortly after, met his death in Queensland. This man used to keep a male donkey – there was no doubt about his sex – in the top reserve, and he would entertain the residents of The Hill half the night calling to his mate. This was supposed to be funny.

There was no sewerage in those days though some had connected with drains laid for stormwater.

A newspaper called The Free Lance was published by a man named Drury, a very capable journalist, who liked his pint like most old-time newspaper men. There was to be a ceremony of turning the sod, or declaring open in connection with the extension of the railway – I think it was Narrabri. The Minister passed through Newcastle where he stayed for some time and Drury secured copies of the speeches to be delivered by the prominent members of the party. On the evening of the day appointed, the Free Lance made a scoop with the publication and description of the ceremony, and all the speeches made thereat. Unfortunately, owing to rain the function had to be postponed for a couple of days and had not been held.

Captain Kirkaldy, a fine-looking man, was head of the Volunteer Artillery and, with the Naval Brigade under Commander Gardner, and the 4th Regiment with their red coats, made quite a colourful picture on state occasions. The permanent artillery always contained a few good athletes. One, I remember, threw a cricket ball for a wager 130 yards on the cricket ground and broke his arm doing it.

Bus owners were Messrs James, H. Lawrence, Bunn, Cuthbertson, James, Morris, Probert, Easton, Jones. Bunn’s stables were at the Dog and Rat, and one not far from Betty Bunn’s crossing at Lambton.

Later a driver of a Tighes Hill bus (Ned Jennings) rode a horse over the Perkin St. high-level footbridge. It was a chestnut by Syd Hewson’s black trotting horse Viking, out of Charley Spruce’s Jenny. The horse was ridden up the steps and along the bridge where the rider dismounted and and led him down.

A boxing match between a local (we had good men in those days) and a coloured man. The latter to “lay down” viz., to be beaten, was arranged, but the trainer of the black man (X) was not in the joke and backed his man. The stakeholder heard the news and, to make hay while the going was good, backed the white man, investing the whole of the stake money.

When he saw how the fight was going X so abused the blackfellow that he was afraid to lose, and the white man, who had not trained, tired and could not continue. The stakeholder had lost the whole of the stake money.

Around where the Sacred Heart R.C. Church is at Hamilton – I forget whether the Church was there at the time – there was scrub where we used to get ”five-corners” and those evil-smelling berries. As we marched into school we would quietly drop them behind us.

When the stink of the berries made itself felt the headmaster would examine the soles of our boots and the poor devil who had crushed the berries would have to fall out and get caned. Of course the real offenders escaped, for the berries were dropped behind – a rather mean trick, but kids think such things funny.

The C. of E. used to have their Sunday School Picnic at Sandgate on the edge of the swamp.

Crimping was the order of the day. Though it was usually a· drunken sailor who was “shanghaied”, occasionally, a navvy – or country man would be shipped away. One night I was at the boat harbour when I saw about six or eight “dead marines’” placed in a waterman’s skiff with all the necessary gear. Each man had a rig-out: sea boots, bed, oilskin, and canvas bag, etc. The boat was very heavily laden (in charge of Old Bill). He offered to take me with him – I was about ten years old and, accepting, he pulled to a ship in the stream, where the drunken men were hauled up by block and tackle from the yard arm, and swung aboard like so many sacks of potatoes. The ship sailed first thing next morning and when these fellows awakened they would be miles out at sea, probably out of sight of land.

Jack Sullivan; boarding house keeper, whose place was near the present site of R. Hall and Sons, was the greatest practical joker. A body of sailors went to Wallsend one Sunday (outside the ten mile limit) to get drunk. They were on horseback and, acting Sullivan’s instructions, when they returned after dark, each carried a broken bottle which he held by the neck, a lighted candle in each bottle, as they had been told they had to carry a light.

Morrison and Bearby, engineers, used to manufacture very fine marine engines. They had a great reputation.

Dick and Arthur Went, two fine athletes, lived near the Customs House. Both were fine runners. I saw Dick Went, in Scott Street, do a standing jump of thirteen feet.

Going to the bank one day I was given twenty pounds too much. My father sent me with a note to the teller asking him to call when he finished work. He called and my father gave him the money. It was a good lesson to me never to start arguments in a bank.

Racecourse was “The Wallaby”

Where the Newcastle Racecourse is now was scrubland known as “the Wallaby”. One night a lot of Hamilton young men ran a handicap of 100 yards footrace. One of the contestants was a young schoolteacher who later became one of the Department’s outstanding inspectors. He had felt a little stiffness and was given some “speedy oil” which he placed in the only bottle he possessed, which was. a red ink bottle. After rubbing down in the dark, before the event, he appeared on the track a noble red man.

One of the practical jokers went a little too far on one occasion. A sailor who had been ill quietly passed away one afternoon. One of the “runners” shanghaiing some men took the dead man along and lashed the body to the mast – he collected his five pounds per head for each man, including the corpse. It took a lot of hushing up.

Old George Hunt. a coloured man, had a seaman’s boarding house where the Scott Street entrance of the Centennial Hotel is now. He was also a successful horse trainer. He had two good horses – Buglelight and Tickerabeen.

Frank Dickson was the postman who did Hunter Street. Many of the shipping people would time their journey so that they would meet him – no matter who he met their mail would be handed to them; he was a wizard.

With Dicky Pattison and one other who I cannot recall, he used to swim from the Bogey Hole to the Gulf. If I remember rightly there is a ledge of rock uncovered at low tide outside the Bogey Hole and it was from this rock they would start. There were no shark accidents in those days.

Much beautiful cedar was brought down from Clarence Town in the Favourite and the Coraki and the Williams.

Swarming with rats

Most premises in Scott Street were swarming with rats, only a few occupiers bothering about them. We depended on cats and traps, principally the latter, whilst our neighbours on either side each had a bull-terrier. When they demolished Chidgey’s store in Newcomen Street, one of the bull-terriers, a powerful dog, had dead rats scattered all over the street, I doubt if one got away – as the men took up the floor the rats were driven into the street.

Henry Buchanan, I think he was Mayor at. the time, convened a meeting of boys to form a Harrier Club and Athletic Club for boys. I can remember of those present: Jack Buchanan, George and Charley Brown (they are around the district somewhere still) and George Turner, who died a few years later. Mr Buchanan installed me as chairman and I understood it was necessary to keep order with a stick. Mr. Buchanan then left the room and closed the door. We were of course all too young, we did not know what to do, but I remember we had a couple of paper chases. This was, however, the direct cause of the formation of the Centennial Harriers (Jack Donnison, Monty Cooke and others), and which eventually went on to become the Centennial Football Club, a very fast, successful and hard-playing team of Union.

The Ship Inn was at the corner of Hunter and Bolton Streets, opposite the Criterion Hotel and Bill Grahame had a tobacconist store next door where he conducted place consultations. Doctor Beeston was in practice at the corner of King and Bolton Streets and he used to lance boils for us. George Firkin was his dispenser. Porter the coal merchant had a lot of two horse drays. He changed and fitted the drays with springs and thereafter one horse could do the work formerly done by two. Despite this lesson of many years ago there are still public bodies using the old type drays. Newcastle was the first city in the Commonwealth to successfully establish the electric light in the time of Colin Christie, Mayor. It was also the first to swing arc lamps over the streets, a suggestion by my father, Robert Reay, when in business in Hunter Street.

Opening the Corporation Baths

The town pump – the caretaker being the town bellman (radio not then thought of) – who enjoyed the name of “Hot Coffee”, was situated where the arcade is in Hunter St. Afterwards the Newcomen Street baths were opened by George Webb, a fine citizen who I think ruined himself in fighting for the improvement of the city. The night of the opening the practical jokers had to have their fun and my father early got the whisper that two pounds was available to anybody who pushed him in at the opening ceremony. Just as a ceremony commenced Dad immediately grasped an iron post with both arms. In the middle of the Mayor’s speech the lights were turned off and everything was in darkness. They immediately went on when the glamorous constable was seen struggling in the water. He was fished out and afterwards claimed his watch was spoilt. The money was soon subscribed for him to buy another. He was as glamorous as a film star: the ladies simply raved over him. He arrived in town at 5pm and made history in the kitchen of the Paragon Hotel before six the next morning when the milkman called. There was a fish shop presided over by a Greek named Andrew. He was a fine fellow had been married 17 years and no children. He was very fond of children and some nine months after the arrival of the glamorous one he was presented with a bonnie bouncing boy bearing a remarkable likeness to big boy blue. To see Andrew marching down the street displaying the baby was supposed to be a joke. He was very happy even if his happiness had been thrust upon him.

These baths were a failure. Like all indoor cold baths, without the effects of the sun the water gets too cold. Our best swimmers at carnivals in the baths were “Kanga” Trevellyn, Dicky Pattison and Chum Harris. Of course swimming has advanced out of all knowledge but those men were streamlined athletes.

When a minister of the Crown came to town he was always treated to a banquet. My father with other businessmen used to attend all of them the ticket cost one guinea.

The shipping column of The Newcastle Herald and Miners Advocate was known all over the world. Years later in San Francisco (Frisco to us) in company with several sea captains the conversation turned on the shipping news and The Newcastle Herald was given the palm for reliable and general information as to the movement of shipping: it was a feature. As long as I can remember Mr John Ralston was in charge of that column and it is a mystery to me that those interested in the history of the port do not make it worth his while to publish his knowledge of the past.

R.B. Wallace, John Wood and Joseph Wood were very prominent men. Mr Stewart Keightley was owner of The Newcastle Herald, which had a number of good athletes on its staff.

Arise Sir Dougal

There was a well-known character belonging to a good family who was just a little off his mental balance. In these days he would have been scientifically treated and been quite alright. We see it done daily now. His name was Dougal and he was the victim of a joke that influenced his whole life. It all started at a performance in the Victoria Theatre when he was presented to the audience and a long legal document, heavily sealed, reported to have been signed by Queen Victoria authorising the authorities to confer a knighthood upon Dougal. He knelt and the master of ceremonies touched him on the shoulder with a small toy riding whip having a whistle on the handle and announced “Arise Sir Dougal”. He was ever afterwards known as Sir Dougal. Another document declared the Queen had forwarded a bag of watches to him as a present and they would arrive by the Sydney steamer on a certain day. At the appointed time the sides of the gangway leading to the steamer were removed and the bag of watches (in reality a bag of spuds) on a hand truck pushed by a seaman appeared. Quite a crowd with Sir Dougal were waiting on the wharf and a cheer went up when the bag of watches appeared. In crossing the gangplank one of the wheels of the truck “accidentally” slipped over the edge and the bag of watches went into the harbour. Sir Dougal, not to be outdone stripped and dived after them but was unsuccessful. He never received them. Whenever one met Sir Dougal after that he would ask to see your watch. He would then open it and write down the number. When Lord Carrington the Governor came to the city Sir Dougal, with a tin star upon a small round red ink wiper on his breast and his hair brushed over nicely, was on the wharf and I remember Lord Carrington giving a start and then quickly sensing a joke bowed gracefully to Sir Dougal. At the reception at the Great Northern Hotel an officious policeman stopped Sir Dougal from going in with the official party. When the Mayor arrived he linked his arm with that of Sir Dougal and they both went past the guard to the applause of the crowd. Sir Dougal was a decent respectable citizen and even if the lads had their fun they resented any slight being given him.

The elections were rowdy events. The great contest between James Fletcher and J.C. Ellis ended in a pitched battle near the Customs House. The supporters of Ellis had two lorries. On each was a lifeboat (Ellis was a ship owner). Hunter Street was crowded with people and these lorries went down Hunter street but when they tried to return the opposition – which was growing fast – were interfering with them. The attacks were being repulsed all along Hunter Street but the opposing forces were gathering strength until the vehicles turned into Watt street and tried to escape. A great cry went up and the crowd surged over the lorries at the Customs House and smashed the boats into pieces. I was an interested spectator notwithstanding a heavy cold. My mother had placed two mustard plasters fore and aft on me, and in the excitement I completely forgot them and landed home raw and sore.

The Centennial hotel was built by Walter Sidney as mine host: a colourful character who later established a bank offering 12% for deposits. It went with the other banks later. Lambton Council borrowed £20,000 and lighted the municipality with electricity. They knew the revenue could not meet the interest but as most of the aldermen had nothing the red rag scheme was pushed ahead. Afterwards the only man who had anything lost his home which was seized. Eventually a receiver Mr McDonald was placed in charge. Horse-drawn buses with the means of transit. Messrs Probert of Lambton, Cuthbertson of Plattsburg and others ran buses, usually three horses – a pair on the pole and a leader. Sometimes they would have exciting races. The fare to Wallsend was one shilling and when youngsters rode up on the steps of the back the cry “Whip behind!,” would be heard.

The wreck of the Briar Holme

This beautiful vessel met her tragic end in 1904. She was barque-rigged, an iron boat with rather more beam than the average clipper-built vessel. She was painted grey with black ports and a broad black band on top of the painted ports: black square on a white background. Built for exhibition in connection with the Paris Exhibition, she had been constructed regardless of expense with plenty of brass-work and artistic fittings. On her last voyage she sailed for London from Hobart in September 1904 under the command of Captain Rich, an experienced and skilful seamen who was making his last voyage. When she was three months overdue and much anxiety felt on her account some fisherman landed on a bleak and unfrequented part of the west coast of Tasmania. On the beach they found sundry packages and articles of cargo. Footprints and the remains of a rude hut gave indications of a tragic wreck. An extensive search was made but no other sign of wreck or men, living or dead, could be found. When the fishermen returned to Hobart the articles were officially identified as portion of the cargo of the Briar Holme. Following this the Government sent out a cargo steamer with a large search party, and remains of the wreck were found underwater. Although the countryside was thoroughly searched, fires lit and guns fired, no survivor was discovered and the party had to return to Hobart. Some weeks later the fishermen who had made the original discovery returned to the spot and landed. This time they met a man who was found to be the sole survivor of the ill-fated Briar Holme. He told a sad story of privation and of his countless efforts to find some kind of habitation, of his unsuccessful attempts to build a raft and how every attempted journey inland ended in a forced return to the coast for food from the wreck. He officially reported that the Briar Holme arrived off the South West Cape of Tasmania at night during thick weather and was hove to with the intention of waiting until daylight. Being north of the fairway however and having overrun her distance she crashed on the rocks and rapidly broke up. A slightly different story was current and one I think nearer the truth. It was: In very heavy weather with poor visibility she went to go about and missed stays and her proximity to the rocks prevented another attempt and she struck the rocks with a fearful crash in the darkness no one had a chance. The two stories are given, for the latter – wherever it originated – was believed by most skippers to be the correct solution. The fact that a specially built vessel like the Briar Holme was smashed up quickly was evidence that there was a tremendous sea running at the time. Such was the end of what was the most beautiful barque to ever grace the waters of Port Hunter.

The Escape of HMS Calliope

An event which stirred the British Empire and shipping ports like Newcastle in particular was the sensational escape of this British warship from the great Samoan Hurricane of 1889. Warships of all the great nations were peacefully at anchor, some with their fires banked, and some with their fires drawn. British warships are always kept more or less in a state of readiness for emergencies and the Calliope’s fires were only slightly banked.

The hurricane came with startling suddenness and almost immediately some of the vessels started to drag their anchors. Admiral Glossop, who commanded the Sydney when she sank the Emden in the First World War, was a midshipman on the Orlando – the flagship of the Australian squadron – but was lent to the Calliope and was on board that vessel that day. Here is a description from the pen of another middy, after describing in detail how the American and German warships drifted ashore one by one and how the Calliope had many narrow escapes from fouling other ships or grounding on the coral reef. “Strenuous efforts were made to get up some steam and the engines were put full steam ahead and the remaining cable slipped. The Calliope gathered way very slowly escaping the reef by only a few feet and proceeded under full speed in the teeth of the hurricane. Almost barring the entrance was the United States warship Trenton, and she was drifting ashore. The Calliope had a very exciting time getting past her. Eventually, after it had looked inevitable that the Calliope would collide with the Trenton, by magnificent management of the helm the bows swept clear of the Trenton by a few feet. As they passed the doomed Trenton, fast drifting ashore, the crew of that vessel gave three ringing cheers which were instantly responded to. They were now out of reach of the rocks but by no means out of danger for the seas were something terrific, stated one of the officers later. A little later it was possible to look around the ship. Under the forecastle were the remains of the carpenters’ tools chests etcetera flipping about in all directions. It was not safe to remain there any length of time. The whole upper deck was being continually washed by tremendous seas and everything that was movable was being washed from side to side. The lower deck was also flooded. In the steerage were the men who were hurt as they could not be put in sick bays which had been washed right out. The midshipmens’ chests were rolling about in all directions. The piano was giving the men of the relieving tackles a tune to every roll. The whole ship looked like a regular bedlam. The storm abated on St Patrick’s day and the Calliope returned to Apia. All other vessels in the harbour of Apia were either sunk or piled up on the reef. The episode sent a thrill of pride around the British Empire.

The River Steamers

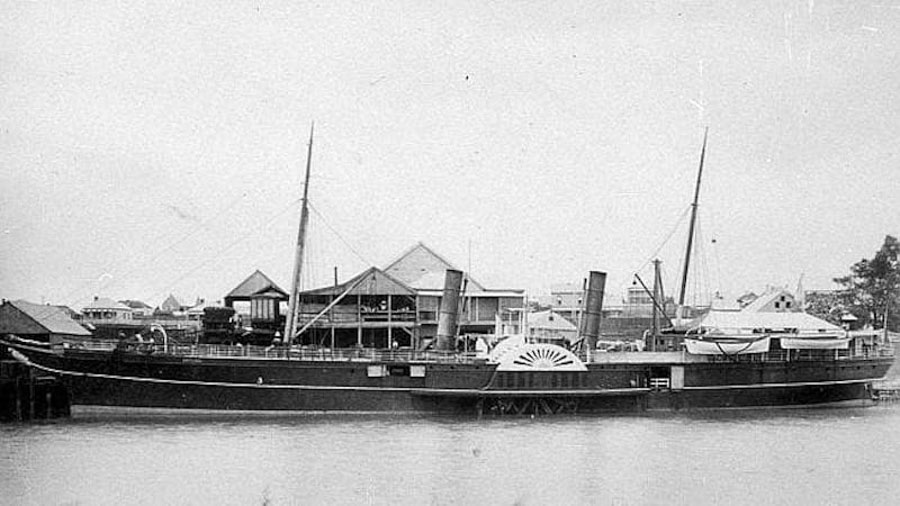

All of the Sydney steamers, viz. those operated by the Newcastle SS Co, Hunter River Co, excepting the Newcastle, regularly traded to Morpeth. They were the Kembla, Coonanbarra, Sydney, Maitland, Morpeth, Lady Bowen, Newcastle and Namoi. The Sydney was previously the City of Brisbane. She had more beam that the others and a very comfortable boat to travel in. These were all fine ocean-going paddle-wheel steamers, with ample accommodation for passengers. The Newcastle made only one trip to Morpeth and, owing to the difficulty in turning her, never went back again. The screw boats Lubra, Gwydir, Hunter and Archer, as well as the stern-wheelers Paterson and Anna Maria all traded up the river. At times there were at Morpeth the Namoi or Sydney, Archer and a couple of stern-wheelers, so that Morpeth was a busy place.

A lucky escape

Upon one occasion the SS Hunter was travelling to Newcastle from Morpeth when she bumped Green Rocks (where the Chichester pipe crosses the river). An examination was made and as she appeared all right she went on to Newcastle and the next day took a large crowd for an excursion to Port Stephens. On reaching Sydney on her usual run she was docked for examination and it was found a large rent had been made in her hull. Her watertight compartments had provided such buoyancy that her accident had not affected her.

Asleep in the deep

Upon another occasion the Hunter carried 400 tonnes of lead to Sydney, which had to be trans-shipped into a lighter. The Hunter was anchored in one of the bays along North Shore. The barge was laid alongside just at dusk and the unloading was to take place next morning. A well-educated Englishman who used to do odd jobs for the company was installed on the punt as watchman. During the night he had retired early to sleep – as all good watchmen do. The water so frequently seen discharging from the sides of steamers – bilgewater -started to flow. This water was being directly discharged into the hold of the punt and gradually she filled and sank. When the lighter was raised later the negligent watchman was still in his bunk and still asleep. The barge had filled so very slowly it had apparently drowned him without awakening him.

The White Ribbon Army

When the Salvation Army first arrived in Newcastle it met with much good natured opposition. However what started in fun developed into a serious matter and the White Ribbon Army had to be suppressed. A band of men started to imitate the Salvation Army by marching down the street and, getting onto vacant land, would testify to being deep-dyed sinners and then take up a collection which at first was spent in wetting their whistle after the dry singing. However the collections from those enjoying the fun raised a problem and it was decided to utilise the money in buying uniforms. Tom Collins was the leader; Lieutenant Paddy Carlon was second in command and Liverpool was presented with a trombone having a large open-mouthed dragon’s head from which the sound came. One of the hymns was: “There is a boarding house not far away, where you get steak and onions three times a day. Oh how the boarders yell, when they hear the dinner bell. How sweet the onions smell, three times a day”. There was never anything of offensive, though some would sing very loudly when passing the Salvation Army. There were three officers dressed in best broadcloth with a wide white ribbon sash over their left shoulder. The climax arrived one night when the opposing forces met head-on. Neither would give way, though the whites were in the wrong and attempted rough house tactics. But the Salvation Army defended themselves and emerged with honour. I saw it and do not think either Collins – who always kept them under control – or Paddy Carlin – though notorious was ever noted for the assistance he gave to the police and was never before the court – were present that night. Later Collins and Carlon were arrested, bailed out and the White Ribbon Army was finished. Had they behaved themselves they would have made a pot of money, for the collections embarrassed them. It really helped the Salvation Army in the long run.

A beer-drinking exploit

Beer in those days was Wood and Toohey brands. Woods, they said, had more body and was preferred by the coal trimmers. It was supposed to be good fighting beer. The casks were put into cellars from whence they were pumped through lead pipes into pewters, long-sleevers, mediums and smalls. An old bummer named Dalton used to call around the hotels at opening time each morning to get the first beer drawn through the pipes, which was usually thrown away. In fact the hotel keepers – or most of them – would not allow this to be drunk by anyone. Dalton however managed to get a considerable quantity. He must have consumed a considerable quantity before breakfast but no one had ever seen it take any effect. One day the SS Maitland was lying at the wharf which was covered with casks of Tooheys beer. I was on the wharf and saw a wharfie pretend to stop a leak in one cask with a small stick. Unfortunately the more he tried the greater the leak until it was necessary to call for assistance from other wharfies who were idling about, probably waiting to start work. By this time the cork bung had been driven in a billy can was produced and the owner’s health toasted good and often.

A fireman on the Maitland threw a heaving line across and the billy, filled with golden fluid, made several successful trips across the water. After this had gone on for some time Dalton appeared. Most of the men resented his presence but others, just getting mellow, offered him a billy can full if he would permit them to afterwards duck him in the boat harbour. He drank his quota and a little extra, and they all then adjourned to the boat harbour and, hooking the heavy hook of the hand crane through Dalton’s narrow belt, hauled him to the top of the crane’s jib. This was a good height and the chain a very heavy one. Swinging him over the water they started to lower him but the chain was so heavy that his weight would not lower it and Dalton was suspended in mid-air. A general conference was held to devise means of getting him down. It reminded one of, “curfew shall not ring tonight” for “twixt heaven and earth his form suspended while the chain swung to and fro”. After sometime Paddy Carlon came along and immediately volunteered to climb up and add his weight to Dalton’s to bring the chain down. He did, but the crowd then decided to duck Paddy, and quite forgetting Dalton on the hook, nearly drowned him.

As there were no pictures in those days this little story is inserted to illustrate the amusements along the waterfront.

Upon another occasion Dalton was told that if he could drink a quart of beer through a funnel he would receive a gift of another quart. When only a tablespoonful was left he gulped for breath. It was such a valiant effort he was given the extra quart which he dispatched with gusto.

Pro Bono Publico

Most of the following appeared in The Maitland Mercury, written by the author, and created such interest that I was inundated with letters from various parts of the Commonwealth. It was this interest displayed in the “Memories of the Hunter” that inspired this booklet. I therefore offer no apologies for inserting them herein.

Ned Kelly and art

Harry Hutchins was the greatest runner of his day. I saw him give Alf Trinder 1 1/2 yards start in 130 yards and beat him. Anytime he ran Charlie Samuels he gave him about three yards start. When Trinder was beaten he (Trinder) ran 11 yards slower than when he won the Botany. Bob Watson beating the English champion Hewitt, and Watson’s offsider King Hedley going to America and beating them all their stamped Watson the champion of the world. Yet we in Maitland have no public memorial to remind posterity of his great record.

Solly and Bailey both started off the seven yards mark in the 130 yard 100 pound Sheffield handicap: the distance being too far for Sully. Bobby Bailey won the final and invested his savings in a fleet of double-decker buses (horse drawn). Success was too much for him and he died a young man. J.P. “Jimmy” Walsh was the scratch man at the rink (Olympic Hall, Bolton Street, where Moroney’s handicaps were run had previously been a skating rink). Bob Fitzsimmons had the shoulders and chest of a heavyweight with light legs. He was K-legged – such men are hard to knock off their feet. Like all great Australian fighters of his day he was a wily customer. He held the middleweight championship when he met and defeated J.J. Corbett for the heavyweight championship of the world. Billy Murphy (eight stone 10 pounds) whom I knew very well, won the featherweight championship of the world by defeating Ike Weir. There is little doubt but that Peter Jackson, the pride of Australia, would have cleaned up Americas’ best and won the heavyweight crown for Australia had not the colour line been drawn against him. He was a kindly coloured gentleman and gave me my only boxing lesson. That is the reason I am often amused at what I read in the press. There are good stories about all the old fighters: Jim Fogarty “the Jawbreaker”, Martin Costello, Jack Molloy “Saucerface” Jack Adlard, Fred Bonner, Frank Pain etcetera etcetera.

Now regarding Searle and Stansbury (scullers): They met once and Searle won. One was 20 years of age and the other one a year older. Searle, a streamlined athlete returning to Australia – he was then champion of the world – died about a year later at Colombo. Later Stansbury’s speed and stamina probably improved, but we surely could have expected Searle to have improved to an equal extent. George Towns, who defeated Stansbury at the second attempt and regained the world championship, will always be remembered by NSW sportsmen. Stansbury had been beaten on the Thames by Gadaur the Canadian, who was then 44 years of age. When Stansbury came home no one would take him on, so he returned to his old occupation, cutting telegraph poles.

George Towns, at the age of 38, determined to try to bring the championship back to Australia. He worked his passage to England, worked his way across to Canada and, using the Australian short boat (24ft, 6 inches) beat Gadaur at Rat Portage over the usual Canadian course of three miles with one turn. In a letter I received from George Towns on Saturday last, he states that he will be 77 on the 18th inst (last year). I was sorry he wrote that for, as the years pass by it is well to forget one’s age. To be continually reminding oneself that the wings are sprouting is a sign of age, destroys morale and leads to early cremation. Sir Henry Parkes realised this for, when over 90, he married a lass of 16 and begat children when nearly 100. What a man. [Thanks to reader Mark. R. Watson for this correction to Audley Reay’s remarks: “Sir Henry certainly led a ‘colourful’ private life! He married his first wife (Clarinda) in 1836 and they were married for 52 years, producing 12 children. A year after her death, Parkes (then 74) married a much younger woman, Eleanor Dixon (32). They had five children – three of whom were born, ahem, before they were married. When second wife Eleanor died aged just 38, the 80 year old Sir Henry promptly married his 23 year old housekeeper! They had no children and Sir Henry died six months later, still 20 years short of his ton”.]

Sporting recollections

George Towns tells a good story of old Bill Beach (the Lion-hearted) who, returning victoriously from England was during a storm in the Red Sea annoyed by a wire flapping outside the open porthole near his bunk. He hauled it in and coiled it at his feet. It was the lightning conductor.

Re Bruce Robertson: his career was, in my opinion, spoiled by the scurvy treatment he received on his return. Like George Towns he worked his passage home and brought home the bacon. Unless I am greatly mistaken his father was George Robertson, a poet of great merit. One of his poems in my possession was set to music and is a delightful song.

Concerning Ned Kelly and art, I remember going to Maitland to see the Show. Large lifesize portraits in oils by Mahony, of Australian bushrangers. On the outside was a huge portrait of Ned Kelly with his rifle pointed at the onlooker. Underneath were the words: “The outlaw covers you, stand where you will”. The spruiker announced: “Three thousand square feet of canvas – every picture being a startling episode, a thrilling incident in the life of Australia’s most daring bushranger”.

Memories of the Hunter (revised with minor additions)

Believing as I do that the Hunter River will someday again be opened for traffic by steam ships as far as the old Wharf behind Cohen’s store in the city of Maitland itself, your “Silent River” leader (Maitland Daily Mercury) led me to approach several persons with a view of getting their recollections published for our perusal. Each one has been keenly interested but their memories failed them.

The recent article on the steamship Hunter was grand reading to those who remembered the many boats and personalities trading on the river. I was surprised to read the Hunter praised so highly. She was certainly a well-built boat: very staunch, practically no vibration from the engines, built in great strength for a particular job. Wonderful gear for handling cargo (for those days). For river or harbour work a pretty well-found screw steamship. As a sea boat she confounded her critics – of whom I was one – by successful voyages in terrific weather. She had excessive top hamper and was hardly on the run before sailors began to speak of her extraordinary behaviour at sea. She was flat-bottomed to carry heavy cargo from the Sulphide works. Her flat bottom would probably reduce her harbour dues. The excessive top-hamper was later removed, but she still misbehaved and whist passengers liked her, sailors all along the harbour-front shook their heads and said it was merely a matter of time when she would capsize. After one trip I avoided her, but later my brother and I had to go to Newcastle in haste and we booked our berths, went aboard and went to sleep. She was a fine boat to travel in from Newcastle to Sydney when she was heavily laden, but it was on the return trip from Sydney, in much lighter trim, that frightened seamen. During the night I was awakened and found the Hunter behaving in a most peculiar manner. I have travelled on many vessels but never have I had such an experience. She did not roll evenly (we were not in a cross sea). The weather was very dirty and there was a big sea running. She would roll to the port side only slightly and then give a long, quick roll to starboard and a quick long roll to port. It was not done alternately as might be expected. I looked at my brother and he was sleeping peacefully and I realised that if she capsized, as I was firmly convinced she would before the night was over, we would have no chance. I decided to let him sleep and, getting a nice cigar (it was before the days of rationing), lighted it and waited.

A nervous voyage on the Hunter

We are told that at such times all our past life rises up before us, but I distinctly remember my thoughts were on the possibility of saving our skins if we went on deck – but I realised it would happen so quickly we wouldn’t have a chance. Yet the Hunter traded for years and proved she could take it in all weathers – but sailors didn’t like her.

My earliest recollections of the river boats was the steamer Kembla, a paddlewheel, hurricane-decked vessel, that her skipper, Captain Skinner took out in all weathers. She was a pretty little steamer and, as the railway to Sydney had not been then built, she carried the mail. These boats, running to Sydney, were very convenient for Newcastle people. We used to post our letters on board right up to 11 pm, when the gang planks were removed, and the letters would be delivered in first delivery in Sydney next morning, equal to existing lettergram. One of her officers, Neilson, was with the company many years and rose to be her master. He was in charge of the Sydney years later. He was a very fine seaman and, on board. a host in himself.

Captain Skinner made the Kembla famous by going out irrespective of the weather and I remember, on several occasions being one of a good crowd of people on the breakwater about midnight to see her cross the bar. I think there was about 20 feet of water there at the time. It was a sight worth seeing for, at times she would be almost out of the water, then plunging from a great height, her bows going under and the great waves rolling right over her. It was probably her shallow draught that rendered it possible, for a large vessel could hardly have crossed in such weather without touching the bottom and breaking her back.

When the Newcastle, the last word in paddle passenger steamers, arrived, the company gave the people of Newcastle a free ocean excursion. Of course she was crowded with people who rarely, if ever, travelled by sea, and her sides had to be hosed down on her return: for the passengers had thrown overboard everything but the anchor. Giving the Kembla a half hour’s start the Newcastle caught and went round her at Big Redhead and returned to port. She was painted green with three white funnels and, I think, six boilers. Her saloon was constructed of birdseye maple which, when the Newcastle was broken up at the· end of her career, was carefully packed pack to England. On her trial the Newcastle did 21 knots.

The first volunteers for South Africa travelled on the Newcastle, with the Fourth Regiment Band (Capt. Barkell) they marched from Arnott’s paddock to the strains of Soldiers of the Queen.

Another river boat was The Favourite, Captain Miller, running to Clarence Town, bringing cedar and hay. A regular traveller was Michael Keegan, with his famous Cow Brand Butter. One of his sons once rode the winner of a horse race in High St, West Maitland, from the Post Office to the Mercury Office. The Favourite and her skipper were very popular – meals and. refreshments were provided.

A former resident of Raymond Terrace gave me a graphic account of that town in the early days. There were some fifty teams trading from Raymond Terrace to Barrington, and wild scene were often witnessed. A wild steeplechase took place in the main street – the hurdles being formed of barrels of beer – he gave the name of the man who rode the winner (now a most respected citizen of another town) whom he described as “the wildest colonial boy.” The Favourite was built at Clarence Town. Painted green, she had been rightly named.

The principal ferry was the Saucy Jack and later, the old Blue Bell, whilst many tugs of J.&A. Brown, viz. paddleboats Bungaree, Goolwa, Prince Alfred and, later, the powerful Stormcock and Gamecock. I saw the latter in Sydney just a week ago, still going strong. And Dalton’s paddleboat Cobra with her coal skip filled with pig iron with block and tackle. She, when towing a boat, would take a list and when such occurred they would haul the skip to the other side to bring her back on an even keel. There were a couple of stern-wheelers, the Anna Maria and Paterson bringing hay and red cedar down the river. Rowing boats of watermen – skiff-type – also brought produce from the Islands.

Owned by my old friend, Jim Chambers, the racehorse Posinatus travelled down the river and then to Sydney in the Archer, en route for Melbourne where, ridden by Albert Shanahan, he won the Melbourne Cup. Getting to the front Shanahan slowed the field down for the first mile, then broke away and won by several lengths. As a picture of the finish shows, he was going better than any of the others at the finish. While on the subject of horses – for Newcastle was always fond of horses – Hypatia, a white mare, travelled by the Kembla and owing to fog, was twelve hours on the trip. She walked to Randwick and won the Flying.

I was in the first train to take passengers to Sydney before the Hawkesbury bridge was built, and we crossed the river in the General Gordon. Mr Goodchap, one of the Commissioners; and fond of the racing game, had all the doors locked and we had the pleasure of seeing Mr Rouse’s mare Vespasia, carefully placed on board the boat before we were let out.

In just touching the fringe of my recollections, some little pleasure might be given to the old hands have been branded “not wanted on the voyage” of life, and who, living in the past, are gradually forced into second childhood. To them I say: “Let memory’s kiss live in today – forget the past”.

What a fantastic record of Newcastle in the 1880s provided by Mr Reay. But in respect of his comments on Sir Henry Parkes (“when over 90, he married a lass of 16 and begat children when nearly 100. What a man.”) he is not quite right – although Sir Henry certainly led a ‘colourful’ private life! He married his first wife (Clarinda) in 1836 and they were married for 52 years, producing 12 children. A year after her death, Parkes (then 74) married a much younger woman, Eleanor Dixon (32). They had five children – three of whom were born, ahem, before they were married. When second wife Eleanor died aged just 38, the 80 year old Sir Henry promptly married his 23 year old housekeeper! They had no children and Sir Henry died six months later, still 20 years short of his ton. His entry in the ADB notes somewhat wryly that: ” [his] fiery integrity bit through in his scorn for the world’s judgment of his marital and financial affairs and his inner resources provided resilience to weather crises which might have destroyed other men.” Cheers to both Mr Reay and Sir Henry.